Reviews 2014

✭✭✭✩✩

music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, book by George Furth, directed by Gary Griffin

Theatre 20, Berkeley Street Theatre, Toronto

June 27-July 13, 2014

Bobby: “Someone to force you to care”

There are two reasons to see Theatre 20’s new production of Stephen Sondheim’s Company. First, it is a rare opportunity to see a legendary but seldom-produced musical by the reigning master of American musical theatre. Second, Theatre 20 has assembled an exceptionally starry cast. It is a pleasure simply to see so many famous Canadian performers on stage together for the first – and most likely the last – time. Unfortunately, the production demonstrates quite clearly why Company is so seldom produced. George Furth’s book for the musical which was so innovative in 1970 when it premiered, now seems hopelessly dated and seriously flawed in its basic conception.

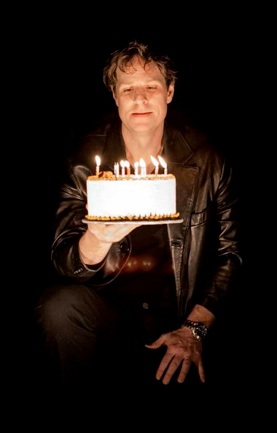

Company was so radical when it first appeared because it was the first musical to be organized according to theme instead of plot. Sondheim would develop this new type of musical from Follies that premiered in 1971 through Assassins in 1990. The theme that ties Company together is marriage. It is the 35th birthday of Bobby (Dan Chameroy) and all his friends, consisting of five married couples, have gathered to give him a surprise party. Now that Bobby has entered middle-age (at least according to the dialogue), his friends all begin to wonder why he is not married. The trouble is that Bobby is indecisive. Not only can he not decide whether to marry or not he can’t choose among the three girlfriends he is juggling.

In 1990 Sondheim and Furth revised the libretto which had already become dated. Yet, they left in references which still date the musical. Characters talk about the “generation gap” and about non-hip people being “square”. One character is embarrassed that her husband is dancing freestyle, as we would call it, and not holding his partner. Another couple has taken up “karate” but it is evident from the demonstration they give that Furth has confused karate with judo, Japanese martial arts being new to the West in 1970.

More important than all these minor quibbles is the general notion behind the musical that men should marry after having sown their wild oats and worse that all women ultimately desire to marry. This notion, that no amount of revising can eliminate, shows the survival into 1970 of attitudes we associate more with the conservative 1950s and early ’60s. The title refers both to a group of people and to companionship. Bobby’s final song is an ode to the value of a lifelong companion: “Someone to crowd you with love, / Someone to force you to care, / Someone to make you come through, / Who'll always be there, / As frightened as you / Of being alive”.

That a person must be married to this lifelong companion is part of the antiquated mindset of the show. Furth does provide an example of a couple who divorce in order to be happier together, but they are the comic exception that proves the rule.

If the background philosophy of the musical is old-fashioned, the musical’s very structure prevents our becoming involved. The musical came about when Harold Prince told Sondheim than a series of one-act plays by Furth would make a good musical. The structure of a series of miniature skits still survives, where Furth has Bobby visit one of the couples and observe how they interact before one or more of them break into song. The trouble is that the dialogue of Furth’s skits is so far inferior to Sondheim’s songs. It would have been better if Sondheim could have characterized the five different couples in song rather than having to use Furth’s dialogue. The consequence is that we have to suffer through the inanity of Furth’s spoken sections to reach the payoff of Sondheim’s music.

These are difficulties that even the most imaginative direction cannot overcome. Gary Griffin’s direction for Theatre 20 is pedestrian and an overall sense of tentativeness suggests the piece is underrehearsed. This only helps to highlight the work’s flaws.

The show does have a high-powered cast that includes Brent Carver, Jeff Lillico, Nora McLellan, Louise Pitre, Carly Street, Steven Sutcliffe and Nia Vardalos. It is great to see them all together on the same stage. Yet, while their individual songs are well done and they sing well as a chorus, they seldom bring off Furth’s spoken skits.

Eliza-Jane Scott and David Keeley play Susan and Peter, the second couple Bobby visits. The main humour of their relationship is that they divorced to live more happily together as if “marriage” itself were some kind of hindrance. It turns out that Peter is bisexual and although Furth treats this as a joke, at least Griffin and Keeley do not. Keeley’s reaction to Bobby’s turning Peter down becomes one of the few moments of authentic emotion in the show. Susan is supposed to be from the South, but you would never know it from the variable accent Scott adopts.

As the pot-smoking Jenny and David, Nia Vardalos and Steven Sutcliffe become the most believable couple in the show. While Vardalos radiates love for David, Sutcliffe brings out a surprisingly menacing side to David’s disdain for Jenny’s “squareness”.

Carly Street plays Amy, a Catholic, who gets a bad case of cold feet just before she is supposed to marry her Jewish boyfriend Paul (Jeff Lillico). Sondheim gives Amy an incredibly fast patter-song. Street fluffs a whole verse but amazingly manages to get back on track immediately. Furth, who generally portrays women as mentally incompetent, gives Amy a long incoherent monologue explaining why she can’t marry such a wonderful guy like Paul, and it is to Street’s credit that she is able to make any sense of it at all.

We don’t meet the last couple, Joanne and Larry, played by real-life couple Louise Pitre and W. Joe Matheson, until the second act. Furth has styled Joanne as the ultimate rich bitch, who does even remember all the men she has married and divorced. Yet, in Larry she has found the one man who is willing to put up with her. Pitre sings what is probably the most famous song in the show, “The Ladies Who Lunch”, one woman’s withering condemnation of all other women. Pitre pours such venom and intensity into this song that it is almost worth seeing the show for this one electrifying moment.

Marisa McIntyre, Lindsey Frazier and Cleopatra Williams play April, Kathy and Marta, the three young women Bobby is dating. Kathy is undercharacterized and Frazier can’t do much to make her interesting. Marta ought to be a hippie but in this production is turned into a punk rocker, which doesn’t suit at all her attitude of loving everyone in her neighbourhood. April is a stewardess whom Furth portrayed in his clichéd fashion as extremely stupid. Luckily, Griffin and McIntyre are able to turn this stereotype around to make April funny not because she is dumb but because she is innocent.

Dan Chameroy, who was in the original Toronto casts of Les Misérables, Miss Saigon and Beauty and the Beast, finally, after too many years, has a chance to show off his singing talent in Toronto. He gives a a fine account “Someone Is Waiting”, “Marry Me a Little” and especially “Being Alive”, which he invests with so much emotion that it rivals Pitre’s “The Ladies Who Lunch” as the most powerful vocal performance of the show.

The five-piece jazz ensemble led by Scott Christian is top notch. The costume design by Ken MacDonald and Michelle Tracey is confusing. The goal is perhaps to represent styles from 1970 onwards to give the work a sense of universality, but overall is looks like a mishmash without any overall unity of colour or cut. Griffin stages the show as if it took place in a nightclub with all the characters not involved in a scene sitting as cocktail tables and looking on.

For music theatre buffs, Company will be a must since the chances to see it are so few and the Theatre 20 cast is made up of so many well-known people. General theatre-goers may wish to see some of their favourite performers on stage but will likely find the show a not entirely satisfying relic of the early ’70s. Intellectually, one can see how important Company is as the first non-narrative musical. Emotionally, however, one tends to feel nothing for any of the characters and generally glad that we live a society that has moved past labelling people with the binary categories of married or single .

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Eliza-Jane Scott, Joe Matheson, Nia Vardalos, Louise Pitre, Brent Carver, Steven Sutcliffe, Nora McLellan, Jeff Lillico and Dan Chameroy; Dan Chameroy as Bobby. ©2014 Riyad Mustapha.

For tickets, visit www.theatre20.com.

2014-06-28

Company