Reviews 2016

✭✭✭✩✩

conceived and directed by Tracey Power

Firehall Arts Centre, Theatre Passe Muraille, Toronto

February 4-21, 2016

“It’s written on the walls of this hotel

You go to heaven once you've been to hell” (“Paper Thin Hotel”)

Ever since it premiered in 2012 in Vancouver, Chelsea Hotel has played to sold-out houses across Canada. That points to the long lasting power of Canada’s premiere singer-songwriter who has been a force in Canadian music since his first album back in 1967. Those expecting some sort of reverent tribute to Cohen in Chelsea Hotel should know right from the start that’s not the point of the show. If you want to hear Cohen’s songs performed as closely as possible to the originals, you won’t get it. Instead, the show demonstrates how Cohen’s songs can survive a wide range of arrangements quite different from those Cohen recorded.

Tracey Power, who conceived and directs the show, has taken 32 of Cohen’s songs and has had Steven Charles arrange them for six performers – three male, three female – who sing them solo or in groupings up to a sextet, sometimes a cappella, sometimes accompanying themselves on instruments. The six play a range of 17 instruments from electric guitar to cello to drum, accordion and kazoos.

Power has invented a suggestion of plot for the songs. We see Jonathan Gould as The Writer, apparently suffering from writer’s block, busy at his desk scribbling on paper and then discarding it in the shabby hotel room that Marshall McMahen has designed that, taking a cue from one of Cohen’s songs, literally has paper thin walls. The Writer’s bed is buried under a mountain of crumpled sheets of paper and a red neon sign pulses on and off through an unseen window.

During the first song, “The Guests” (1979), we meet the rest of the cast. Ben Elliott is The Bellhop, tall and apparently enjoying The Writer’s misery. There is Sean Cronin as The Sideman, probably the least theatrically defined of the group in look or function. There are Rachel Aberle and Tracy Power as The Sisters of Mercy, who first appear as hotel maids before taking on other identities as various women who attract The Writer. Finally, there is Christina Cuglietta as Jane, the woman from “Famous Blue Raincoat” (1971). She looks slightly mad with twists of cloth in her hair and, unlike the others, emerges from the mountain of paper as if she were somehow the cause of The Writer’s inability to write.

Costume designer Barbara Clayden has given the show the look of a 1930s Berlin cabaret since all the cast except The Writer wear pancake makeup with emphasized lips and eyebrows. In contrast with The Writer, the guests are all in black and white, some with writing on their clothes, the only modern touch being the black sneakers worn by The Bellhop and The Sideman.

The design thus does not try to recreate the atmosphere of the actual Chelsea Hotel, where Cohen and so many other famous people stayed over the years. Rather it turns the hotel into a type of theatrical carnival apparently representing Cohen’s mind, inhabited by caricatures and other figures distorted by memory. Why this memory should look like a 1930s Berlin cabaret, a type of theatre more associated with satire and politics than personal love and loss, is not at all clear.

The fundamental question Power’s scenario raises is whether staging Cohen’s songs in this way helps or hinders our understanding them. Chelsea Hotel is poised halfway between a back catalogue musical like Mamma Mia! (1999) and a revue like Jacques Brel is Alive and Well and Living in Paris (1968). In the first Catherine Johnson wrote a book that provided a narrative context in which the songs by ABBA could appear. They were orchestrated differently from the originals and their meaning narrowed both by their narrative function and by being sung by characters rather than singers-as-singers. In the second Eric Blau and Mort Schuman translated Brel’s songs and arranged them in an order in which songs are linked by similarity or contrast, moving in general from the idea of the third song “Alone” to the final song “If We Only Had Love”. Here each of the four singers – two male, two female – functions as a singer not a character and tries to give the best performance of a song that he or she can.

Chelsea Hotel is halfway between these without the benefit of either. In Chelsea Hotel, Power does give us a strong enough story to justify the character-like delivery and often humorous orchestrations of the songs. Except for Jonathan Gould and occasionally Tracey Power and Christina Cuglietta, Cohen’s songs are delivered offhand as they would be in a catalogue musical, as if the point were not to perform the song in the most effective way possible but simply to perform it to contribute to the carnivalesque environment Power has created. Unsurprisingly, Gould, with his soft sweet voice caressing the words, is the one performer who gives the impression of trying to give the best rendition he can of each number.

It is great to hear Cohen’s songs sing in different orchestration and by a variety of singers, but one doesn’t leave the show feeling that Cohen’s work has been honoured in the way the Jacques Brel clearly honours Brel. Chelsea Hotel is about how differently Cohen’s songs can be delivered rather than how well. There’s no question of how amazingly multitalented the cast is. The question is whether the show’s general grotesquerie best represents complex songs that are so full of sadness, regret and emotion.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

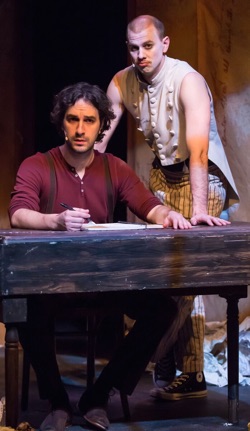

Photos: (from top) Rachel Aberle, Sean Cronin, Ben Elliott, Christina Cuglietta and Tracey Power; Jonathan Gould and Ben Elliott. ©2016 Racheal McCaig.

For tickets, visit www.artsboxoffice.ca.

2016-02-10

Chelsea Hotel: The Songs of Leonard Cohen