Reviews 2016

✭✭✩✩✩

written and directed by Judith Thompson

Factory Theatre, Toronto

March 24-April 10, 2016

Sandy: “Being dead ain't that different than being alive— it's like moving to Brockville or Oshawa”

Premiering in 1980, The Crackwalker is Judith Thompson’s first play and the one that brought her to national attention. It ends Factory Theatre’s “naked” season of “Canadian classics reimagined”. In this case, “reimagined” is the operative word since Thompson has not revived the 1980 version of her play but her 2011 revision of it and has substantially changed the function of the title character.

Thompson’s play is a portrait of the underclass in Kingston, Ontario. There had been portraits of outcasts in Canadian society before The Crackwalker such as Marcel Dubé’s Zone in 1953, George Ryga’s The Ecstasy of Rita Joe and John Herbert’s Fortune and Men’s Eyes both in 1967 and Rex Deverell’s Boiler Room Suite in 1977. Thompson’s play stands out for its lack of sentimentality and determination not to view its characters as heroes or martyrs.

The play contrasts two sets of couples – the working class Sandy (Claire Armstrong) and Joe (Greg Gale) with the working poor Theresa (Yolanda Bonnell) and Alan (Stephen Joffe). The two sets experience opposite changes of fortune. Sandy and Joe move from near break-up to reconciliation, while Theresa and Alan move from relative happiness to tragedy.

In the original version of the play the Crackwalker was a First Nations man, drunk or high on drugs, known to all the characters from the streets of Kingston. He particularly haunted the nights of Claire and the days of Alan, representing for both an even further low that they feared to sink to.

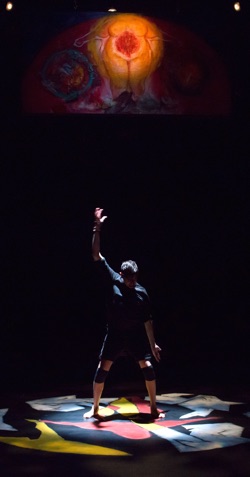

Otherwise, Thompson has the Crackwalker cause the characters to move as if they were marionettes under his control, often pulling them back on stage via a force emanating from his fingers when they wish to exit. Otherwise, he wears masks representing people the characters mention in their conversations, like Theresa’s cousin’s dead baby. Sometimes he even represents objects as in one scene where is both Theresa’s own baby and an oven.

One can understand why Thompson would want to transform a passive figure seen as a kind of bogeyman into an active figure with power and, indeed, Fobister gives a very intense, committed performance. But Thompson has not escaped the central difficulty with the Crackwalker figure – namely using a First Nations man as symbol rather than as a person. In fact, in Thompson’s revision he is even more of a symbol than before since, given his gestural language, he has become an embodiment of fate who is manipulating the characters.

This change has a negative effect on the play because it now makes the characters appear as victims of of pre-ordained destiny rather than as victims of their own choices. Why all four characters are prone to making such terrible choices is one of the main questions that the original version of the play posed. Now that inquiry is aborted by making the characters’ choices subject to the influence of a pseudo-magical figure. One sees the same problem in productions of Shakespeare’s Macbeth where the director has decided that the Witches are in direct control of the action with Macbeth and his wife as their puppets. This approach removes the richness of the play in investigating human decisions and what leads to them.

And so it is here where Thompson’s series of sometimes powerful scenes of people’s internal contradictions leads nowhere. As a director Thompson further negates our engagement with the characters by continually allowing the tension to flag or stop altogether rather than to build . This happens particularly through her insertion of several songs and through the dance interludes of the Crackwalker.

Thompson is better at the what, where and when of the other characters than the how or why. Sandy is in an abusive relationship with Joe, who brags about sleeping with other women, yet she stays in the relationship. This would be a chance for Thompson to explore why women stay in such relationships, but she only tells us that Sandy does, not why she does except for loneliness which, given Joe’s brutality, does not seem a sufficient reason. We know that Sandy is friends with the mentally challenged Theresa, but how or why that came about is a mystery. Theresa herself has a monologue but it does nothing to explain her mental processes or why telling the truth and lying are so similar to her.

Given the the hazy characterization and the unexplained turnabouts in behaviour of her characters, the actors have to concentrate on making them as believable as possible. Generally, they do, especially Yolanda Bonnell as Theresa, but they are still hampered by Thompson’s writing and direction. Thompson has created a low-class language for Sandy, Joe and Alan which with all of its “ain’ts” and other peculiarities would make more sense if the play were set in the deep American South rather than in Kingston, Ontario. Claire Armstrong, with her careful diction, communicates such intelligence that it clashes with Sandy’s careless manner of speaking, while Greg Gale and Stephen Joffe speak Thompson’s lingo as if they were pardners from an old movie Western.

Thompson has created a dialect for Theresa that omits all uses of the verb “to be”. Some people may speak this way but on stage it makes Theresa, an aboriginal girl, sound as if Thompson sent her to the Tarzan and Tonto school of racial speech stereotyping. Bonnell exudes a wonderfully warm personality as Theresa, but she is never able to make Thompson’s language sound natural.

Given its reputation as a Canadian classic, audiences will find Thompson’s revision of the play and her direction disappointing. To force us to look at the people middle-class people would like to ignore is good thing, but to help us understand how and why their lives are the way they are would be even better. The parallel rise of Sandy and Joe versus the fall of Theresa and Alan suggests there is no answer. Thompson’s revision that pushes everything onto the unknowable fickleness of fate is not just less helpful but obscurantist. The result is that we see people in unfortunate situations but feel nothing for them – the opposite one would think of what Thompson is trying to achieve. Just as an poet is not always the best reader of her own poetry, so, too, a playwright is not always the best editor or director of her own work.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Stephen Joffe, Yolanda Bonnell, Claire Armstrong and Greg Gale; Waawaate Fobister as the Crackwalker; Greg Gale and Claire Armstrong. ©2016 Joseph Michael Photography.

For tickets, visit www.factorytheatre.ca.

2016-03-26

The Crackwalker