Reviews 2002

✭✭✭✩✩

by William Shakespeare, directed by Miles Potter

Stratford Festival, Festival Theatre, Stratford

May 31-November 2, 2002

"Sacrificed Children"

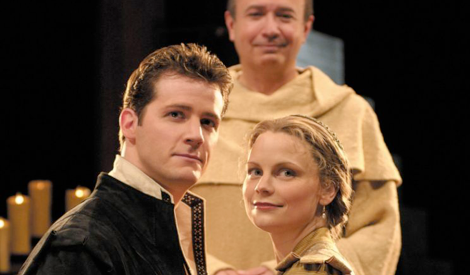

I know I wasn’t the only one who looked at Stratford’s 2002 season line-up and thought, “Not ‘Romeo and Juliet’ again!” Stratford did the play just five years ago in 1997 making the present production the eighth in fifty seasons. Fortunately, director Miles Potter has a new take on the play that many will be interested in seeing: he does it as it’s written. For the first time in twenty years at Stratford the action is set in Renaissance Italy with the actors in period costume. More importantly, Potter has Graham Abbey and Claire Jullien play the star-crossed lovers as the ages specified in the text. This has the beneficial effect of changing how we view these familiar characters and clarifying the themes of the play.

The best “Romeo” I’ve seen was Stratford’s production in 1984 starring Colm Feore and Seana McKenna. There the couple was played as intelligent if impulsive twentysomethings whose verse expressed their thought and inklings of doom. It’s true that people were pushed into adulthood at a much earlier age in Shakespeare’s time, but Shakespeare deliberately lowers Juliet’s age from 16 in his sources to only 13 and emphasizes throughout that Romeo is only a “boy”. Juliet’s father knows that his daughter is of the minimum age to be legally married and advises her and Paris against it. Therefore, Potter does have a case in portraying the couple as physically but not necessarily emotionally mature.

This naturally changes our perception of the play. For one thing, it means that Romeo and Juliet are not fully aware of the implications and ironies of what they say. Both appear as fantasists, more involved in the image each creates of the other than the other in person. Their image-making out of love becomes the parallel of the Montagues’ and Capulets’ image-making out of hatred and thus ties in more clearly with Mercutio’s Queen Mab speech.

There are risks in this approach. When characters don’t fully understand the implications of what they say the result can be unintentional comedy instead of irony or foreboding. Abbey and especially Jullien do not entirely avoid this problem. Potter brings out their youth by giving both tantrums, Romeo sobbing uncontrollably in Friar Laurence’s cell, Juliet screaming at the her parents. This also makes them both seem more childish than tragic. Nevertheless, one wonders if that isn’t closer to the truth of the story that the “stars” bring about the sacrifice of the youngest of each family to end their enmity.

Shakespeare gives Romeo more insight into his fate as he tumbles headlong to his doom and Abbey communicates this fully. He is more successful than Jullien at making Romeo appear youthful without appearing foolish. Jullien gives Juliet’s soliloquies capture no genuine sense of foreboding, making them sound more like a girl’s silly imaginings.

While Potter brings out a freshness in the two leads, he allows two other important characters to wallow in cliché. The normally dependable Keith Dinicol plays Friar Laurence with such exaggeration and in such a plummy voice he seems to be parodying the role. Friar Laurence is a highly ambiguous figure—after all, all of his help merely helps the couple to their doom. Not to suggest some of this ambiguity is a serious flaw. A different problem plagues Lally Cadeau’s performance as the Nurse. Cadeau puts on an old woman’s and the all-purpose Irish accent she uses for lower class characters. As a consequence, half of what she says is incomprehensible. Often we know what she’s saying is supposed to be funny, but we shouldn’t have to guess.

The other roles fare much better. Wayne Best’s Mercutio, who seems old to be friend to this especially young Romeo, has just the right combination of vigour and fantasy. When he delivers the Queen Mab speech he seems to get caught up in his own imaginings and thus provides a powerful example of how Shakespeare views the Veronans (read humanity), including the young lovers.

Patrick Galligan makes Paris a decent, worthy young man. His sincerity makes Juliet’s disdain seem all the more willful. Scott Wentworth is a strong presence as Capulet, making his anger at Juliet not cruel or impulsive but rather the natural reaction of a thwarted father. In contrast, Julia Donovan’s impression of Lady Capulet as a modern socialite seems out of place.

Raymond O’Neill makes a resonant Chorus but does not bring out the weakness in Escalus, who is so unsuccessful in quelling the feud in his own city. Shakespeare doesn’t give Montague and his wife much to do but express anger or sorrow and John Dolan and Sarah Dodd don’t give them much more character. Courtenay J. Stevens has a good comic sense at the Nurse’s servant Peter. As Tybalt Nicolas Van Burek can’t seem to express anger without losing voice control and with it effectiveness. In contrast, Caleb Marshall makes the role of Benvolio much more substantial that it usually is, making the point that Romeo has more people to rely on than Friar Laurence.

Stratford has set “Romeo” in so many different times and places Patrick Clark’s handsome Italian Renaissance costumes have the effect of novelty. With a minimally dressed Festival stage, Steven Hawkins’s moody lighting is chiefly responsible for sustaining a tone of ill omen. John Stead’s fights, especially the central one between Mercutio and Tybalt, look so dangerous you’ll wince.

Miles Potter’s “Romeo” shows what new ideas can arise simply by a closer examination of the text. If the cast is uneven and cannot make everything in the play work as it should, Potter’s interpretation will challenge assumptions about how the title characters should be portrayed. Let’s hope for more text-based explorations of Shakespeare in the future.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: Claire Jullien, Keith Dinicol and Graham Abbey. ©2002 Stratford Festival.

2002-07-08

Romeo and Juliet