Reviews 2004

✭✭✭✭✭

by Githa Sowerby, directed by Jackie Maxwell

Shaw Festival, Court House Theatre, Niagara-on-the-Lake

June 19-October 9, 2004

"Shattering"

It’s good to see that new Shaw Festival Artistic Director Jackie Maxwell is continuing the practice of former Artistic Director Christopher Newton in producing rarities from the Shaw Festival mandate. Last year saw the delightful woman’s adventure comedy “Diana of Dobson’s” (1908) by Cicely Hamilton. This year sees the gripping drama “Rutherford and Son” (1912) by Githa Sowerby (1876-1970). You won’t likely have heard of either playwright or play before, but the impact of this superb production is one you won’t soon forget.

Like “Diana”, “Rutherford” was brought again to people’s attention by its inclusion in the anthology “New Woman Plays” (Methuen, 1991) edited by Linda Fitzsimmons and Viv Gardner. This led to a production at the Royal National Theatre in 1994 and to its being named one of the RNT’s “Plays of the Century”. The Shaw’s presentation is the first professional production in Canada.

Where “Diana” was characterized by frothy optimism, “Rutherford” is dominated by a dour pessimism. It concerns Rutherford, tyrannical both as head of his family and of his glass-making company located in a city not unlike Newcastle-upon-Tyne, where Sowerby’s own father was a glass manufacturer. Both the family and the company are in trouble. Rutherford’s eldest son Richard has joined the church. His second son John shows no inclination to work, much less take over the family business. He, his wife Mary and new baby have moved back to the family home “temporarily” until he sorts things out. Rutherford’s daughter Janet seems likely never to marry. John claims to have invented a process that would reduce the cost of producing glass, but rather than giving the formula to his father and thus help turn the business around, he means to patent it and sell it to the highest bidder. To get a experienced judgment, he has shown Rutherford’s longtime foreman the formula, but Rutherford, of course, sees no need to buy what he can get for free.

Unlike Shaw’s plays where characters freely express their opinions at great length, Sowerby creates a realistic North Yorkshire household where if people have opinions they keep them to themselves. The play immediately takes on a modern edge by the great swaths of silence that surround characters’ words. As director Jackie Maxwell says in her insightful programme note, she and the cast came to explore “how much is conveyed by what is NOT said.” When they can no longer be held in any longer emotions do burst out, but what characterizes the Rutherford household and Maxwell’s production is the mounting sense of tension as anger and hatred build up inside the characters. The vehement way Kelli Fox as Janet sets the table for dinner at the start of the play communicates years of pent-up frustration and loathing. Due to Maxwell’s minutely detailed direction we often learn as much from how characters silently react to a speech as from the speech itself.

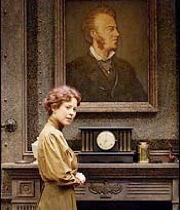

Designer William Schmuck has created a dark panelled wall for the stern living-room where all the action is set. All seems normal until one notices that the panels seem to be held on by rivets. Under Louise Guinand’s subtle lighting the Rutherford’s living-room can appear more a factory or a prison, as Rutherford’s children claim, than a home. The room is also a crucible for the family’s emotions. In Act 2 when Janet finally breaks her silence and tells Rutherford how he has ruined her life, in a marvellous effect, the walls beginning with the fireplace and slowly spreading outward begin to glow red hot.

The cast and performances could not be bettered. Michael Ball has played quite a few disagreeable old men but nothing quite as intense as Rutherford, who moves with the calm deliberation and piercing gaze of a dragon in his lair. Like his children, he, too, is filled with repressed anger and frustration. He knows times have changed and are leaving him behind. He has thought that life is work but has seen that all this work in the end amounts to nothing.

Part of the point of Sowerby’s play is that the strict patriarchy Rutherford represents ultimately results in its own undoing since it crushes all those beneath it who could carry it on. All three Rutherford children are shown to be weak, all sense of self-worth nearly trampled out of them. Mike Shara’s Richard, head bowed, voice small, unable to meet others’ eyes, seems to be saying “Don’t hurt me” with every move. It’s clear he has sought the church as an escape. Dylan Trowbridge’s John is the most defensive and most confrontational. He expends so much energy to puff himself up to appear strong that it has the opposite effect. His shying away from discussing important matters with Mary bodes ill for their future. If we didn’t have confirmation from Rutherford’s foreman Martin, we would likely doubt if John had made a real discovery at all.

From a feminist point of view Janet is the most obvious victim of patriarchy. She stays in the house doing the work of servants just to save her self from boredom. Her only hope of escape lies in marriage yet Rutherford lets her see no one because no one in town is good enough for her. Yet, Sowerby has painted a more complex portrait than one might expect. She shows that Janet is not Ibsen’s Nora. Janet herself thinks only a husband can be her salvation. Grumble as she does when Rutherford is absent, she is compliant when he is present. The big blow-up in Act 2 is brought on only by Rutherford’s persistent goading. Fox exudes a sullen energy from her first appearance on stage that seems all the more potent for being kept so rigidly under control.

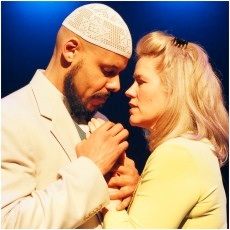

Peter Krantz does an exquisite turn as Rutherford’s foreman Martin. Through him Sowerby expands her critique of society from the evils of patriarchy to social hierarchy itself. Martin has no conception of himself other than as a servant and sees no other virtue in himself but loyalty to his master. Krantz manages to make us see Martin not as dimwitted but as an honest and good man whose world view simply has not encompassed the notion of freedom, even when finally the chains are broken. Nicole Underhay’s character Mary takes a rather different path. For two acts of the play she is seen merely as meek and polite, doing needlework by the fire, out of place in someone else’s house. Yet, when the time comes at the very end, the keenness she has shown in observation comes to the fore in conversation. Underhay shows us a woman, averse to confrontation, forced to adopt a revolutionary way of thinking for the sake of her own survival and her son’s.

Rounding out the cast Mary Haney plays Ann, Rutherford’s sister and defender, grown old before her time with an empty life while Donna Belleville plays Mrs. Henderson, the indignant mother of a hired employee.

Sowerby’s play is remarkable in moving forward toward a conventional tragic ending but not stopping there. The final scene may at first seem a surprise, but in retrospect it presents a vision of a post-tragic world that Sowerby has had in sight from the very start. While her critique of patriarchal and hierarchal power has been trenchant, she suggests the possibility of a revolution from within. “Rutherford and Son” is an exciting find. In this superb production it will have you firmly in its power to the very last moment.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: Nicole Underhay. ©2004 David Cooper.

2004-07-25

Rutherford and Son