Reviews 2004

✭✭✭✩✩

by Samuel Beckett, directed by Albert Schultz

Soulpepper Theatre Company, Premiere Dance Theatre, Toronto

June 17-July 1 & August 20-September 24, 2004

"A Long Wait"

Soulpepper completes its cycle of Samuel Beckett’s full-length plays with his most famous, “Waiting for Godot”. Compared to the company’s productions of “Endgame” in 1999 and “Happy Days” last year, this production is not a great success. One cause is director Albert Schultz’s overly reverential approach to the text that slows what little action there is to a snail’s pace. Another is the fatal miscasting of Jordan Pettle as Estragon opposite William Hutt’s Vladimir. The interaction of Vladimir and Estragon drives the play and when one of the two doesn’t spark, a play that symbolically goes nowhere dramatically go nowhere, too.

To have Vladimir played by an older man and Estragon by a younger is an interesting idea as if the two were father and son or, in this case, perhaps grandfather and grandson. Yet, if that is the idea it’s one that Schultz never explores. He has the two interact, as they do in the text, as if they were just old friends, nothing more. Beckett presents different generations on stage in “Endgame”, but the point in “Godot” that the four characters should be as similar as possible with Pozzo and Lucky as a kind of distorted image of the relationship of Vladimir and Estragon.

This is precisely where the Soulpepper production falls down. Rather than four similar characters roaming John Thompson’s barren, post-apocalyptic landscape, we have four completely dissimilar characters with completely different acting styles. The central idea of Vladimir and Estragon as two halves of one person, the mind and the body, and of Pozzo and Lucky as their warped reflections is almost completely lost. And with that loss is the dynamic between characters and the two groups of characters that makes the play work.

Schultz has Hutt and Pettle play Vladimir and Estragon in a highly realistic way unlike the overt theatricality of Joseph Ziegler and Oliver Dennis as Pozzo and Lucky. Like the great British actors, Hutt acts primarily with his voice. You will likely never hear Beckett’s fragmentary prose sound more like poetry than you will when you hear Hutt speak it. He makes one of Vladimir’s longer speeches sound like an except of “King Lear”: “To all mankind they were addressed, those cries for help still ringing in our ears! But at this place, at this moment in time, all mankind is us, whether we like it or not.” And indeed, when Hutt is playing you can see why some critics have likened the work to Beckett’s take on the scenes in the heath between Lear and the Fool. It is a magnificent and insightful performance.

Sadly, it occurs in a vacuum. Pettle’s best work has been in modern, realistic plays like “Zadie’s Shoes”, where his imprecise diction and tendency to speak too rapidly are more at home. Here, where every one of the few words count, these habits are disastrous. Pettle often fails even to accent the most important word in a phrase. He, thus, is no match for Hutt. What should be a dynamic dialogue becomes more of a monologue by Hutt interrupted by often unintelligible remarks from Pettle.

The appearance of Pozzo and Lucky should suggest that, if we think Vladimir and Estragon have it bad, there is always something worse. Didi and Gogo may be friends who bicker but Pozzo and Lucky are master and slave. Strangely, Schultz brings out much more detail in these two than he does in Vladimir and Estragon. Ziegler seems to be working too hard to make Pozzo a big character, yet the more theatrical he is the less intimidating his character becomes. This is a Pozzo who is more a buffoon than the tyrant he should be. This leave Oliver Dennis to give the most authentically Beckettian performance of the evening inseparably combining the realistic and artificial, the comic and pathetic. His single speech when Lucky “thinks” is a masterful portrayal of the mechanism of the mind in decay.

If Pozzo and Lucky are to reflect Vladimir and Estragon they should bear some resemblance to them. Oddly enough, designer Camellia Koo has clad Pozzo in a spotlessly clean riding outfit. If this is a post-apocalyptic world, how has he alone managed to keep this outfit looking new when all around him are in rags. Other production have shown that Pozzo can be more frightening if dressed like the others, thus making his domineering attitude all the more bizarre.

Schultz has taken a reverential approach to the text seeking out its pathos more than its comedy, when ideally both should be indisseverable. To do this Schultz stretches out some of Beckett’s many “pauses” to the point where the show comes to a complete halt as if the cast were waiting for a freight train to pass. Rather than tragic, the action seems merely enervated and dull. There is so little momentum by the end of Act 1, a newcomer to the play could easily imagine the show was over. One only has to think of Brian Bedford’s production at Stratford in 1996 that emphasized the vaudeville and music-hall background to the routines of all four characters, to realize that “Godot” can be as hilarious as it is tragic and can stand a quicker pace without loss of its serious intent.

In some ways Schultz has taken the “waiting” of the title too literally. After all, the play is not so much about waiting and doing nothing as it is about all the various things we do to entertain ourselves while we are waiting. Despite the performances of Hutt and Dennis, you might well find yourself relieved when Henry Ziegler as the Boy finally appears to say that Mr. Godot is not coming. Then you’ll know you won’t have much longer to wait for the show to end.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

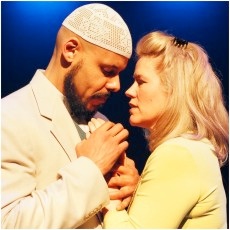

Photo: William Hutt and Jordan Pettle. ©2004 Soulpepper.

2004-09-16

Waiting for Godot