Reviews 2008

✭✭✭✭✩

by George Bernard Shaw, directed by Jackie Maxwell

Shaw Festival, Festival Theatre, Niagara-on-the-Lake

July 18-November 1, 2008

"Mothers and Daughters"

The Shaw Festival’s fourth staging of Shaw’s early controversial work “Mrs. Warren’s Profession” is marred but by some odd design choices but more importantly shines as a showcase for the powerful acting of the two principals. Here’s Shaw’s language is at its most natural and least periphrastic. The play begins in comedy but ends in a moral dilemma that will have you debating long after the curtain goes down.

Mrs. Warren’s profession, to be blunt about it, is prostitution, at first the active participation in it, later the financial managing of it. This being the Victorian era the “p-word” is never mentioned, but Mrs. Warren’s doings were clear enough that it significantly delayed production of the play. Shaw published it in 1898 in a collection appropriately titled “Plays Unpleasant”, but it was banned from public performance until a production in Birmingham in 1925. The first American production was in 1905 but the mayor revoked the theatre’s licence after one performance. When the production re-opened the cast was arrested for “offending the public decency”.

The controversy surrounding the play clearly had to do with Mrs. Warren’s long defence of prostitution as a better trade for a poor girl than working in a whitelead factory and dying of lead poisoning as happened Mrs. Warren’s sister Jane. The play is not an anomaly. In his very first play, “Widowers’ Houses” (1892) the idealistic Doctor Trench discovers that his fiancée’s father is a slumlord. In “Major Barbara” (1905) the title character breaks with her father because he is an arms manufacturer. In all three love is pitted against personal morals. “Widowers’ Houses” and “Major Barbara” arrive at high ambiguous resolutions of the conflict--not so with “Mrs. Warren’s Profession” that moves from a battle through a temporary reconciliation to conclude with a final battle where neither party can be said to “win”.

When we first meet the 22-year-old Vivie Warren, she is happily living in a cottage in Surrey preparing for a job as an actuary. Having grown up in boarding schools she had hardly ever seen her mother and does not even know who her father is. Yet, she has graduated from Cambridge and is emancipated and self-sufficient. Frank Gardner, the son of the neighbouring vicar, would like to marry Vivie but he has nothing to offer and has no knack or even desire to make money. Breaking this idyllic scene is the arrival of Mrs. Kitty Warren, whom Vivie disdains as an uncaring mother because of her nearly constant absence. To set Vivie right, Mrs. Warren will finally have to tell her the truth that she has been protecting Vivie from this knowledge and that she has done everything money can buy to give her daughter an education and opportunities that she never had. After Mrs. Warren’s long ACt II confession, Vivie finds she can forgive her because she is aware enough of the unequal status of men and women to know that prostitution is sometimes the only way for women to earn a living. Yet, there are still things that Mrs. Warren has not revealed. When her slimy business partner Sir George Crofts proposes marriage to Vivie and is rebuffed, he decides to hurt her with the full story.

This is one of Shaw’s most economically written plays and one of the canniest in playing with audience expectations. It begins as a comedy and when mother and daughter reconcile at the end of Act II, it seems it will continue as one. Though comic elements remain, mostly in the form of frank and his father, the mood darkens significantly when Crofts takes charge in Act III and moves to an ending in Act IV that is certainly tragic for the title character. The play was a great success when the Shaw presented it directed by Tadeusz Bradecki in 1997 starring Nora McLellan as Mrs. Warren and Jan Alexandra Smith as Vivie. This production is also a great success and proves, contrary to popular belief that there is room for interpretation in Shaw. Director Jackie Maxwell guides us through the play with such a sure hand that, even if we know the play, we are still surprised at the revelations that progressively darken the tone.

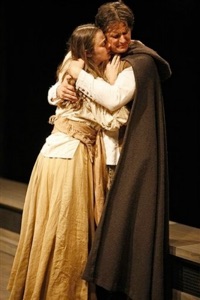

Under Bradecki, McLellan’s Kitty had become such a good imitation of a high-class woman that the production tended to emphasize the theme of appearance versus reality. Under Maxwell, Mary Haney’s Kitty maintains a lower-class accent shows that her fine manners are not inbred. This approach shifts the focus clearly to the play’s social issues. Haney gives powerful performance that captures all the aspects of this multifaceted character--her airs, her vulgarity, her good humour but also her desperation and rage. Moya O’Connell is excellent as Vivie. She shows that Vivie’s education and high-mindedness are also accompanied by a certain degree of self-pride. This seems justified in relation to an oaf like Frank, but becomes problematic in relation to her mother. Kitty is a self-made businesswoman and proud of it. Vivie can be proud of what she has done with her opportunities, but she did not make them for herself but was given them by her mother. O’Connell’s performance is so nuanced that we can understand why she takes the stance she does towards her mother but at the same time see that her high morals are also a result of her very different upbringing. In the fierce clash between the two at the very end, you don’t really want either woman to “win” their debate since we see both sides so clearly.

Except for Crofts, the men in the play are there mostly for comic relief. Andrew Bunker is likeable Frank Gardner, who has no plan in life but to get by on charm and good humour. His very openness about his multiple deficiencies in doing anything useful provide a comic contrast to the earnest studiousness of Vivie. As Frank’s father, Reverend Samuel Gardner, Ric Reid both shows his exasperation at having such a wastrel as a son but also reveals that a wastrel’s life is one not entirely foreign to his own past, thus suggesting a father-son resemblance that parallels the mother-daughter resemblance in determination of Kitty and Vivie. Praed the architect who lives for art and beauty exists primarily as a counterpoint to Crofts the businessman who lives for money and power. Praed is also the rather dreamy opposite to the practical Vivie, who is bored by the arts. David Jansen gives Praed just the right air of old-fashioned gentility, amused by the toughness of the “new woman” but certainly not understanding it. The least likeable character is Sir George Crofts. At the beginning his disdain of Vivie surrounding and collection of friends seems comic, but in Act III his unctuous ways are no longer funny. Benedict Campbell captures this type perfectly and how his assumption of natural class superiority can suddenly turn to the meanest spite when thwarted.

The main peculiarity of the production is Sue LePage’s design. She places Vivie’s cottage house left leaving house right of the stage occupied mostly with greenery. The problem is that once the characters arrive they all congregate and converse in front of Vivie’s cottage. The situation worsens in Act II when Vivie’s cottage is turned around to reveal its interior. Now all the action, including the first important discussion between mother and daughter, takes place in an even smaller space to the extreme house left of the stage. I couldn’t help but feel sorry for those on house right who had to look across so much distance to view this important encounter. Finally, by Act II, LePage uses the full width of the stage for the garden and exterior of Reverend Gardner’s house. However, the ivy that covers all the walls looks more like green cargo netting than ivy. Since the front wall of Vivie’s cottage could be seen through, I assumed that LePage was attempting a non-realistic design, perhaps to reinforce the action of the play in which people finally do see through others’ appearances. Yet, in Act IV, Vivie’s office in Chancery Lane is perfectly realistic and solid. It unfortunately also occupies only the centre third of the stage so again we have to peer into a smallish box to see the action.

Despite these oddities, we inevitably become caught up in the battle between mother and daughter and the more general question it represents of what parents owe their children and vice versa. After Kitty tries every tactic she can think of to justify herself and to assert her rights over her daughter, Vivie says to her, “I am my mother’s daughter. I am like you: I must have work, and must make more money than I spend. But my work is not your work, and my way is not your way. We must part”. To what extent her view is necessary or fair remain unresolved. Thus, Shaw leaves us to continue the debate.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: Mary Haney and Benedict Campbell. ©Emily Cooper.

2008-08-28

Mrs. Warren’s Profession