Reviews 2016

✭✭✭✭✩

by Philip Ridley, directed by John Shooter

Precisely Peter Productions, Double Double Land, 209 Augusta Ave., Toronto

May 5-22, 2016

Cosmo: “People love it. Sitting there in the dark. Having the living daylights scared out of them”

It’s hard to believe that Philip Ridley’s play The Pitchfork Disney was first performed 25 years ago. It feels more modern and more disquieting than many new plays written today. It is said to have launched the “in-yer-face” movement in British drama where sex, violence and grotesque imagery are confrontationally put back on stage. At first glance, Ridley’s play is about the bizarre world two orphans have created for themselves in isolation from the outside world. Take a closer look, and it reveals itself as a modern take on Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1953), relocated from Beckett’s abstract countryside to an indoor, urban setting in London’s East End with all the sex and violence that goes with it. John Shooter has directed a tense and unsettling production highlighted by two outstanding performances.

The site-specific production takes place in an abandoned apartment above the multipurpose performance space Double Double Land in Kensington Market. The entry along the north side of the building lined with trash bins is a perfect introduction to the all-too-realistically grotty apartment of the Stray twins where all the action takes place. Designer George Quan has recreated almost too well the look of an uncleaned, claustrophobic, airless, lightless space where two people have lived for too long. The fact one character vomits centre stage as soon as he enters may push your already compromised comfort level to the barely tolerable setting.

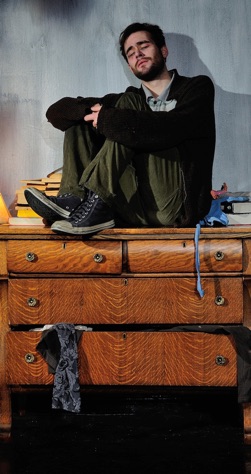

Before that third character enters the apartment, Ridley has already involved us in the suffocating lives of the Stray twins who live there. The 28-year-old twins are Haley (Nikki Duval) and Presley (Justin Miller) – both apparently named for dead rock ’n’ roll stars. They have continued to live the family apartment ten years after their parents’ unexplained death, the catastrophe of their lives from which they have never recovered. Rather than acting like the 18-year-olds they were when their parents’ died, the two have retreated into their prepubescent childhood when thye were happiest. The two subsist entirely on chocolate bars and sleeping pills and whoever has done the makeup for Duval and Miller has made them look quite believably unhealthy.

The most stressful activity for the two is having to leave the apartment to go shopping. The play opens with an argument about what Presley has just bought and about who will have to do the shopping next. Presley agrees that if Haley tells him her worst experience in the outside world he will do all the shopping from then on. She performs her recital of that horrifying experience so well that Presley absolves from ever having to go outside again.

Since Presley already knows about the experience, we have to wonder whether this is one of the many rituals that the twins have invented as a substitute religion in a world without God. In another ritual, Haley questions Presley as if in catechism to describe what the outside world looks like through a crack in their boarded-up window. What Presley describes is a world that is completely black, earth and sky, and utterly destroyed as after a nuclear attack. The conclusion is that they are the only two living and their house the only one standing. A further rite in their personal religion is taking their sleeping pills which they do so kneeling on the bed, each placing the pill in the other’s mouth as if it were a communion wafer.

They take the pills to prevent them from having recurring nightmares. Both dreams involve snakes. Haley’s nightmare concerns getting lost at the zoo just after seeing a snake eat a live mouse and fearing that the wild animals will eat her. While Haley drifts off to sleep for almost the entire second half of the play, Presley does not. This fact, underscored by eerie music by Thomas Ryder Payne, should make us wonder whether the second half of the play is really happening or is Presley’s nightmare come to life.

Like a snake shedding his skin as described earlier by Presley, Cosmo sheds his outer coat to reveal a shiny red coat underneath. Further, Cosmo claims he was hatched from an egg and that he earns lots of money by eating cockroaches and other insects and small mammals in public. Cosmo’s view is that people will pay to be frightened and that everybody needs their little dose of disgust to get them through. Cosmo repeatedly asks Presley if he is gay which Presley repeatedly denies, yet that doesn’t prevent Cosmo from tempting Presley to see whether Presley will finally act on his obvious desire.

In Waiting for Godot, the tramps Vladimir and Estragon play various games in a post-apocalyptic landscape to pass the time while waiting for the mysterious Mr. Godot to appear. The duty to wait is what gives their lives meaning. When the bombastic Pozzo and his slave Lucky appear, the two assume Pozzo may be Godot but discover he is not.

In The Pitchfork Disney, the situation of the Stray children (note the name) is even worse. They do not live in a post-apocalyptic world, but they fantasize that it is to give their bizarre mode of living a purpose. Like Vladimir and Estragon they fundamentally stay alive for each other. But unlike Vladimir and Estragon, Presley and Haley do not even have the duty of waiting to give their life meaning. The imperious Cosmo is very like the theatrical Pozzo and his performing friend Pitchfork, clad in bondage gear including a face mask, is like Pozzo’s performing servant Lucky. Cosmo commands Pitchfork to sing just as Pozzo commands Lucky to speak.

Ridley seems to propose two ways of coping with the modern world. One is the way of the Strays – retreating indoors into a sickly, claustrophobic world of infantilism. The other is the world of Pitchfork and Disney – going outside into a dangerous world of sex, violence and death.

The action shows that a rift is already occurring between Haley and Presley. While Haley wants an excuse never to leave the apartment, Presley go so far, in reality or in his dreams, as to invite the outside world in. This is because, much as he would like to deny it, Presley senses that he is drawn to both violence and sex himself. The violence is demonstrated in his horrific description of killing a snake by frying it alive in a frying pan and then tasting it. The sex, that even Haley notices, is demonstrated in Presley finding himself drawn to “pretty” men and, as his nightmare suggests, even to men who are in no way “pretty”. The play depicts the growing awareness and fear in both Haley and especially Presley that their way of life that has protected them for ten years may not be tenable for long.

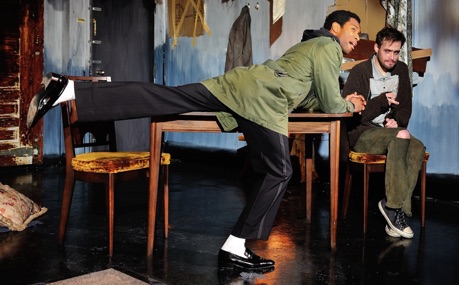

Director John Shooter has drawn especially powerful performances from Justin Miller and Ayinde Blake. Unlike many actor their age, both are able to convey multiple layers of meaning in their every word and gesture. In the long scene between Miller and Blake, Miller shows how desire, disgust, attraction and a strange sort of happiness underlie Presley’s sullen exchanges with Cosmo in a way that never appears in Presley’s exchanges with Haley. Miller’s delivery of Presley’s extremely long account of his nightmare is a tour de force of acting moving as it does from confusion, shock, desire and horror towards ecstasy.

Ayinde Blake is an ideal Cosmo Disney. He shows that Cosmo has learned to put on a tough façade of sophistication to hide an insecurity that may be as great as Presley’s. We have to wonder why Cosmo continues to stay with Presley after he gets over being sick. On the one hand it is to brag about himself and to taunt Presley with being homosexual. On the other, Blake shows that Cosmo seems to need companionship, if not more, as much as Presley does.

Nikki Duval makes Haley a disturbing presence. Haley’s bouts of hysteria are scary and Duval gives a masterful reading of Haley’s tale of being attacked by wild dogs, where one horror is only placed by another. All that is missing is some consciousness on Haley’s part that she is manipulating Presley even if it is through passive aggression. This is important because this makes Presley’s choice in how to live a choice between two types of manipulation – one by his sister, one by outsiders like Cosmo.

We dread the arrival of Pitchfork after all that has been said and Yehuda Fisher’s lurching entrance rather like Frankenstein’s monster at first confirms our fears. But appearances are deceptive. Fisher shows a gift for physical and vocal comedy in Pitchfork’s attempt to stand on a chair and in singing his lullaby.

At nearly two hours without intermission, The Pitchfork Disney is an uncomfortable play to watch in more ways than one. Yet, it is so engrossing that the time seems to fly by. The play is historically important simply given how many subsequent plays it influenced. One need think of Enda Walsh’s many plays like Bedbound (2000) or The Walworth Farce (2006) where people isolated from the outside world have established their own rituals of storytelling, or of Martin McDonagh’s plays like The Lonesome West (1997) and The Pillowman (2003) that combine sibling relations with storytelling and violence.

The only play of Ridley’s Toronto has previously seen is the notorious Mercury Fur (2005) in 2014.* The Pitchfork Disney shows that Ridley’s interest in the nature of morality in a post-apocalyptic, or would-be post-apocalyptic world begin with this his very first play. It’s a shame that Toronto has had to wait so long to see this play since it is one that anyone interested in modern drama should see. Yet, we have to be grateful to Precisely Peter Productions for at last bringing it to our attention on the occasion of its 25th anniversary.

*Correction: Stewart Arnott wrote on May 10 to remind me that he directed a production of Ridley’s Vincent River (2000) for Cart/Horse Theatre in 2011 and that Cynthia Ashperger directed Tender Napalm (2011) at SummerWorks in 2013.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Nikki Duval and Justin Miller; Justin Miller as Presley; Ayinde Blake and Justin Miller. ©2016 Vincente Marana.

For tickets, visit www.brownpapertickets.com/event/2535756.

2016-05-06

The Pitchfork Disney