Reviews 2016

✭✭✩✩✩

by William Shakespeare, adapted by Graham Abbey, directed by Weyni Mengesha & Mitchell Cushman

Stratford Festival, Tom Patterson Theatre, Stratford

June 22-September 24, 2016

Richard II: “How sour sweet music is,

When time is broke and no proportion kept!”

For its 2016 season the Stratford Festival is presenting Shakespeare’s Second Tetralogy of English history plays edited down into only two plays. The first, called Breath of Kings: Rebellion comprises Richard II and Henry IV, Part 1. The second, called Breath of Kings: Redemption comprises Henry IV, Part 2 and Henry V. The notion of presenting these plays in this format is extraordinarily foolish. To compress two Shakespearean plays into one requires removing about half the lines in each. Plays thus eviscerated are not satisfying in themselves or in conjunction.

Though the Stratford Festival has removed the name Shakespeare from its title, it is still the largest Shakespeare festival in North American and likes to regard itself as the guardian of Shakespeare’s heritage on this side of the Atlantic. Previously, it has always presented the plays of the Second Tetralogy as they were written, i.e. as separate plays. One reason for this is that three of the four – Richard II, Henry IV, Part 1 and Henry V – are regarded as masterpieces and are studied as such in university. In 2014, Stratford presented Shakespeare’s King John, one of his lesser history plays, as a full-length play, so it is bizarre to say the least that it would not so with the plays of the Second Tetralogy, especially when these plays have influenced the writing of history plays and their sequels from the rediscovery of Shakespeare in the 18th century to the present.

The idea that the history plays need to be compressed to be palatable is mistake. In fact, multipart history plays have increased in popularity recently. In 2008 when the Royal Shakespeare Company presented full-length productions of all eight plays of both the First and the Second Tetralogies, people from around the world made up the sold-out houses in Stratford-upon-Avon. In April this year the RSC brought a new production of the four full-length plays of the Second Tetralogy to New York after performances in Britain. In 2013 the BBC presented a four-part adaptation of the Second Tetralogy with each part lasting from two to two and-a-half hours. The second season already shown in Britain is a four-part adaptation of the First Tetralogy. Also in 2013 the RSC presented a six-hour stage adaptation Wolf Hall, Parts 1 and 2, based on Hilary Mantel’s novels about Thomas Cromwell in Britain and on Broadway in 2015. In June this year the centrepiece of of Toronto’s Luminato Festival was Rona Munro’s 2014 trilogy of history plays based on much less familiar Scottish history in the form of The James Plays, namely James I, James II and James III, a seven-and-a-half hour long sequence had already been a hit both in Scotland and at the National Theatre.

In his note in the programme for Breath of Kings: Rebellion, it is clear that adaptor Graham Abbey loves the history plays and knows what continues to make them so vital and important. It is therefore even more incomprehensible why he should feel the need to condense them. Editing down Richard II and Henry IV, Part 1 to half their lengths – one hour and 20 minutes for the first, one hour and 15 minutes for the second – destroys their power. Abbey’s primary concern is to make the plot clear, yet so much of the history plays is not about the plot but about the personal, popular, religious and metaphorical context of events.

Abbey’s version of Richard II, strangely enough, does not begin with Shakespeare’s play but with a scene from Act 5 of the anonymous play Thomas of Woodstock (c.1595). In this scene one of Richard II’s favourites, Lapoole, has the title character, who is John of Gaunt’s brother and was regent during Richard’s youth, murdered. Abbey changes the name of the favourite from Lapoole to Bagot, one of the three favourites mentioned in Shakespeare’s play. Abbey then skips forward to Act 1, Scene 2, of Richard II, where John of Gaunt and his wife the Duchess of Gloucester discuss Woodstock’s death. Only after having presented this background history does Abbey present Act 1, Scene 1, concerning the dispute between Henry Bolingbrook and Thomas Mowbray over whether the king’s favourites (meaning in fact the king) were or were not responsible for Woodstock’s death.

Abbey cuts almost all of the debate between the two to rush to Richard’s judgement upon the combatants, Bolingbroke’s exile, Richard’s seizure of the deceased John of Gaunt’s estate, and Bolingbroke’s return to claim the estate and, almost incidentally, Richard’s crown. Abbey leaves in the most famous speeches in the play, or at least parts of them, but they hang on only a skeleton of plot. Without the richness of the circumstances surrounding them and the attendant development of the characters, the famous speeches lose their effect since we haven’t seen all the experiences that they are summing up.

Abbey’s drastic pruning of the play has left the actors little to work with to develop their characters. As Richard II, Tom Rooney is very good at conveying the king’s dominant mode of irony, but he is less able to demonstrate that Richard has a naturally regal demeanour that Bolingbroke can never hope to attain. The point of the joust between Mowbray and Bolingbroke that Abbey has cut is meant to display Richard’s mastery of pomp and ceremony. Rooney, however, also misses Richard’s most intriguing quality – that of self-dramatization. For this Rooney has no excuse because Abbey leaves enough of these key passages in, like Richard’s emotional arrival back in England from Ireland, his descent into the base court and his deposition scene. In the last scene in particular it should be clear that Richard is manipulating the event to his own advantage but neither Rooney nor co-directors Weyni Mengesha and Mitchell Cushman bring this out. It’s terrible that Abbey cuts Richard’s famous face-as-clock metaphor from his final speech.

Abbey, strangely enough, ruins his own role as Henry Bolingbroke, later Henry IV. Though Abbey’s Henry is very well spoken, Abbey has cut most of the speeches that provide a key to his character. In the full text we note that every time Bolingbroke is asked why he has returned from exile to England, he gives a different answer. Abbey gives only his first response in Act 2 but none of his subsequent, more sinister responses about pruning the commonwealth.

Stephen Russell is a fine John of Gaunt, but Mengesha and Cushman oddly have him deliver the most famous speech in the play, “This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England”, facing the southeast corner of the stage and thus away from nearly the entire audience. The one actor who fares best in the condensed play is Randy Hughson as the Duke of York. Hughson ably shows how a man with traditional allegiance to the king is so sorely tested by Richard’s abuse of power that he must finally speak out against him. Yet, York faces a dilemma when he finds he cannot fully support Bolingbroke who would usurp the lawful king’s throne.

Abbey’s editing of Henry IV, Part 1 for Rebellion’s second act is so extreme it feels more like a series of disconnected excerpts. We are meant so see how Henry IV despairs of his son Prince Hal because he spends all his time with the lowlife in Eastcheap, particularly in the company of the renowned rogue and thief, Sir John Falstaff. Henry even admires the manic dedication of Hotspur, the son of his enemy Northumberland, that contrasts to much with disreputable life of his own son. Little does Henry know that Hal has planned this situation deliberately so that his “reformation” will appear the greater when it happens.

Abbey provides us with so short a glimpse of the tavern scenes in Eastcheap that we barely get any idea of what is supposed to be so bad about them. He gives us Hal and Poins’s plan to make a fool of Falstaff, the outcome of this plan and the important scene where Hal and Falstaff trade places playing Hal and King Henry. But that is it. Focussing so tightly on the plot allows no way to give a general view of Shakespeare’s finely drawn portrait of this den of sin.

As for those rebelling against Henry, Abbey gives us Hotspur’s anger about his prisoners, his departure from his wife and his death in battle and no more. There is no Owen Glendower; no Mortimer, for whose hereditary right to the throne the rebels are fighting; and no wife of Mortimer who speaks no English, an important foretaste of Henry V’s wooing of the non-English-speaking Katherine in HenryV as a means to cement his reputation at the rightful ruler of England.

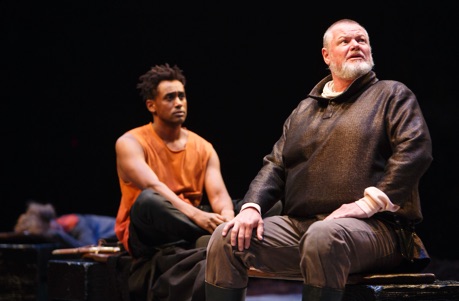

We know this part of the play is in trouble as soon Araya Mengesha opens his mouth. At first we assume he is speaking Shakespeare’s prose in such a contemporary offhand manner, compressing words and dropping final consonants, to show how Hal is trying to fit in in Eastcheap. But then comes his revelatory monologue, “I know you all, and will awhile uphold / The unyoked humour of your idleness”. The switch into verse marks the switch in Hal’s manner from trivial to serious as he coldly outlines how he has been using all his “friends” to enhance his future change. Mengesha, however, marks no such change in manner of speech or mood. Unable to convey more than one sentiment at a time, he fails to illustrate in the remainder of the play Hal’s knowing deception of those around him, especially Falstaff, who have grown to love him.

Mengesha’s largest role in any Shakespeare play before this was as the boy Fleance in Macbeth at Stratford in 2009. Why Araya Mengesha (cousin of co-director Weyni Mengesha) should be dropped into so large a role when he is so manifestly unprepared for it is a mystery. Any time he is paired with another actor of his approximate age – whether Sébastien Heins as John of Lancaster, Gordon S. Miller as Poins or Jonathan Sousa as Hotspur – it is painfully evident that he cannot match the other in diction or in expression of emotion. All this bodes ill for the next two plays in which Hal, later Henry V, is the central character.

Countering the weakness of Mengesha’s Prince Hal is the robust strength of Geraint Wyn Davies’ Falstaff. Wyn Davies looks to be the next great Falstaff at Stratford after Douglas Campbell and James Blendick. He has the characters’s ready ribald wit and humorous love of all the classic vices, but he also communicates a love for his companions, especially Hal, that lends a fatal fragility to this great lover of life. Wyn Davies is such a pleasure to watch you inevitably wish you were seeing the entire play.

Among the younger actors the standout is clearly Jonathan Sousa as Hotspur. The character is constantly in a rage, filled with energy and ready to explode in anger whenever he is crossed. Sousa shows all this yet his diction is crisp and clear and he shows that Hotspur’s volatility is as much a weakness as a strength. In Hotspur’s dying speech, his only speech of reflection, Sousa reveals an entirely different side of the character in his awareness of his own foolishness. It is the most moving moment of the entire evening.

In the 19-member cast are more women than appear in the plays, so that Weyni Mengesha and Cushman have the women play some male roles, although no men play female roles. Thus Kate Hennig shines as both the stern Bishop of Carlisle and the comic Mistress Quickly, Irene Poole is formidable as Lord Scroop and Walter Blunt and Carly Street is a strong woman as Lady Percy and a strong man as the fighting Earl of Douglas.

2016 is the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. Most Shakespeare companies have scheduled something special for this year. This season would, for example, have been the perfect time to stage the entire Second Tetralogy as separate plays or at least to have begun a new full cycle with Richard II. Shakespeare’s two tetralogies of history plays are massive achievements no other of his contemporaries attempted much less matched. It is not until Friedrich Schiller’s Wallenstein trilogy (1799) that a playwright, himself heavily influenced by Shakespeare’s tetralogies, comes close to an epic multi-part drama of this scope.

These are achievements to be embraced by a Shakespeare festival, not shunned, and definitely not stripped of all their meat so that only their bones remain. Breath of Kings: Rebellion is a case where two halves do not make a whole. You leave feeling cheated twice out of a satisfying experience and disappointed that a festival should show the integrity of Shakespeare’s works such disrespect.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Tom Rooney as Richard II and Graham Abbey as Henry Bolingbroke; Carly Street as Douglas and Graham Abbey as Henry IV; Randy Hughson as the Duke of York and Stephen Russell as John of Gaunt; Araya Mengesha as Prince Hal and Geraint Wyn Davies as Falstaff; Jonathan Sousa as Hotspur. ©2016 David Hou.

For tickets, visit www.stratfordfestival.ca.

2016-07-31

Breath of Kings: Rebellion (Richard II & Henry IV, Part 1)