Reviews 2017

✭✭✭✭✭

by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, directed by Marshall Pynkoski

Opera Atelier, Elgin Theatre, Toronto

October 27-November 4, 2017

“Ah! tutti contenti

Saremo così!”

Opera Atelier’s current production of that perennial favourite, Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, is both musically and dramatically the best the company has ever staged. It is also superior to the COC’s last mountings of the work in 2007 and especially in 2016. In fact, if you wish to purge the COC’s lugubrious 2016 version from your mind, OA’s production provides the perfect means to do so. As in the past, director Marshall Pynkoski emphasizes the commedia dell’arte background of the characters and here he has his strongest ever cast of singer/actors.

The present production uses the same colourful Spanish-themed costumes by Martha Mann as in 2010 and the same beautifully painted sets and drops by Gerard Gauci as in 1992, 2003 and 2010. What has changed quite subtly is Pynkoski’s direction. While he retains a general overall formality of posture and movement, the acting itself is the most naturalistic that Pynkoski has yet encouraged. Since Beaumarchais’s play was so revolutionary in 1784 as was Mozart’s opera based on it in 1786, a more modern, less stylized mode of acting only serves to emphasize the new, more analytical way of looking at the world that the story represents.

Pynkoski’s direction emphasizes the one-two punch to established authority delivered by Beaumarchais’s play via Lorenzo Da Ponte’s clever libretto. First, we see the scheming of servants like Figaro, Susanna and Cherubino versus their master, Count Almaviva, who wants to reinstitute his feudal rights of the droigt du seigneur whereby he is allowed to sleep with the new wife of any servant before the servant does. Second, seeing how this plan wrongs the Countess, the focus shifts by the final act into a battle of the sexes with women of both classes Susanna and the Countess, pitted against men of both classes, Figaro and the Count. Cherubino, a female singer playing a boy who later dresses up as a girl, partakes of both plots.

The opera is sung in Jeremy Sams’s lively English translation which itself has been punched up anonymously as when one character refers to something as “not worth half a loonie”. The advantage of singing comic opera in translation is that the audience laughs in response to what happens on stage instead of in reaction to a new surtitle.

As Susanna, Mireille Asselin has a bright, silvery soprano and acts with a pertness that perfectly matches Williams’s sprightly Figaro. Peggy Kriha Dye gives a sensitive performance as the Countess. We can hardly blame the neglected wife for flirting with Cherubino, but Dye reveals the true pain of her lost love in an exquisite account of “Porgi, amor, qualche ristoro” that immediately gives emotional depth to the superficially farcical action. Indeed, Dye’s Countess seems oppressed by care even in the opera’s most comic moments until the Count at last seeks her forgiveness and she grants it him is a “Più docile io sono” rife with mixed emotions.

The Marriage of Figaro presents such a complex microcosm of society that it is possible to envisage various characters at the centre of that microcosm. Many productions try to make Figaro as a trickster the centre, others Cherubino as an innocent or the Countess as a moral touchstone. OA’s present production is the first where the Count himself emerges as the opera’s central character and Pynkoski makes a very convincing case that this is the best approach. After all, the Count’s revival of his droigt du seigneur initiates the problem of the action, his repeated tricking by the others makes up the body of the opera and his realization of the folly of his ways is what brings the action to a close.

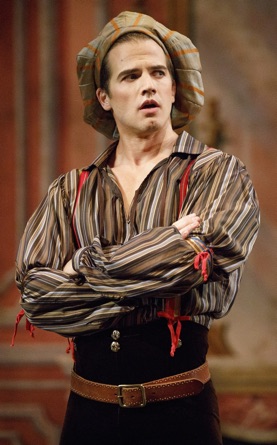

Thus, despite the charisma of bass-baritone Douglas Williams as Figaro, it is the authority of bass-baritone Stephen Hegedus as the Count, no matter how often it is undermined, that Pynkoski has made the central focus of the action. In contrast to the smoothness and suppleness of Williams’ voice, Hegedus’s is stern and solid. Like the rest of the cast, Hegedus is also a fine actor and he is able to make the Count’s 180º turnabout from rage to pleading for forgiveness in “Contessa perdono!” absolutely believable and, along with the Countess’s mercy, the most moving sequence in the entire opera.

The true free spirit of Figaro is Cherubino and Mireille Lebel is an ideal incarnation of that character. Blessed with a strong expressive mezzo-soprano, Lebel conveys all the boyish playfulness and foolishness that make him so beloved of the Countess and Susanna without ever becoming cloying. Lebel’s singing of Cherubino’s two most famous arias “Non so più cosa son” and “Voi che sapete che cosa è amor” are as near perfect as can be.

The surrounding cast of characters are all well done. Laura Pudwell, an expert comedienne with a rich mezzo, can make us laugh at Marcellina’s hauteur just by sucking in her cheeks or tucking in her chin. Gustav Andreassen is a Dr. Bartolo with a full enough voice to support his words of menace. Christopher Enns, his features unfortunately hidden by his full-face mask, sings the roles of Basilio and Don Curzio freely without resorting to crimping his tone or using a stutter as happens far too often in productions of Figaro including those by OA. Olivier Laquerre is very funny as the dim-witted gardener Antonio and Grace Lee is a pure-voiced Barberina.

The 32-strong Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra produced a glorious sound under conductor David Fallis, with spirited harpsichord accompaniment of the recitatives by Charlotte Nediger. Fallis seemed concerned to insure that the opera came in under the Toronto stage union’s three-hour limit, and so his tempi were generally faster than usual and he had to suppress frequent impulses for applause for individual arias. The time-limit had the side benefit of giving the action unimpedible forward momentum and coherence.

Opera Atelier’s Figaro has always been the most visually appealing Figaro Toronto has ever seen, whether in Dora Rust-d’Eye arrestingly colourful costumes or in Martha Mann’s more subdued designs. Jeannette Lajeunnesse Zingg’s dance sequences have always enlivened the opera in a way that few opera companies have the means to do. Now with an ideal cast and Pynkoski’s depth of insight into the work that so well balances the action between the formal and the naturalistic, OA’s latest Figaro has set the benchmark for all future productions of the opera in Toronto. It is a magnificent achievement – and immensely enjoyable besides.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Mireille Asselin as Susanna, Peggy Kriha Dye as the Countess and Mirielle Lebel as Cherubino; Douglas Williams as Figaro; Stephen Hegedus as the Count (standing centre) and the ensemble . ©2017 Bruce Zinger.

For tickets, visit https://operaatelier.com.

2017-11-04

The Marriage of Figaro