Reviews 2001

✭✭✭✩✩

by Ferdinand Bruckner, translated by Daphne Moore, directed by Ed Roy

Theatre Voce, Berkeley Street Theatre Upstairs, Toronto

January 19-February 3, 2001

“A Surprisingly Modern Play from 1926”

Overt lesbianism, drug abuse, mercy killing, descent into prostitution, psychosexual mindgames--all these are themes one might possibly expect in a current neo-noir movie. But they are all found in “Pains of Youth”, a play from 1926 by the German playwright Ferdinand Bruckner, only now receiving its Canadian première by Theatre Voce. This production shows that the praise for Lillian Hellman, Tennessee Williams or Edward Albee for bringing such subject matter to the stage is really the result of a kind of cultural amnesia. Bruckner’s play is only one of many written in Germany between the wars with a daring in content and structure that still amazes. Plays by Frank Wedekind, like “Spring Awakening” (1891) and the two “Lulu” plays (1895), may have paved the way for Bruckner, but he takes Wedekind’s examinations of sex and depravity out of their semi-mythological context and reveals them, disturbingly, among the youth of his own time.

The German title for “Pains of Youth “ is “Krankheit der Jugend”, i.e. “Sickness of Youth” which is a more accurate clue to the multilevel themes of play. Not only does the action taken place among a group of medical students but the play is a dissection of the directionless society between the wars that has produced a generation oppressed by confusion and purposelessness. The first discussion in the play as two friend cram for a medical exam is about phthisis (tuberculosis), symbolic of youth’s sickness as an incurable disease characterized by a wasting away of the body from within. While the students are supposedly learning to heal others, they seek distraction from their anomie by lacerating each other. The parallels to today’s youth are very clear and since Daphne Moore’s (not entirely fluent) translation was produced in London in 1987, there have been a spate of student and professional productions in the UK and US. Thanks to Theatre Voce, we in Canada finally have a chance to see why.

Director Ed Roy’s neo-Expressionist production is brilliant. The boarding house where the action takes place is shown first from the outside covered with projections of various anatomical drawings. Consistent with this and the theme of the play, the house, like a body, is opened up to reveal Marie’s room where the heart of the action is located. David Wootton has designed a slanted asymmetric bed as the focus for the room where the furniture otherwise consists entirely of piles of oversized books. Wootton thus neatly captures the conflict between intellect and desire that fills the play. Wootton surrounds Marie’s room with two translucent wings, which in tandem with Michael’s Kruse’s imaginative lighting, become opaque when lit from the front, but when lit from behind show the play of sharp, distorted shadows of those in adjacent rooms capturing the eerie look of “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari”. In the powerful scene when Marie’s life is shattered, she smashes a (paper) mirror on the wall, but the lit cracks spread beyond the bounds of the frame to cover the whole room. Angela Thomas’s costumes neatly bring out the nature of each character within the confines of a 1920s style--from the prudery of Irene to the seductiveness of Desiree. Shane MacKinnon and Kevin Quain play Quain’s catchy Weillian music which you’ll find hard to get out of your head. Roy has the two begin the action by making their way around the set before we ever see the characters, rather as if they were leading its doomed inhabitants on a dance of death.

To act in or view a play like this requires an adjustment to a style few North Americans have experienced. Bruckner, like the earlier Expressionists, writes staccato-like dialogue with few words per line. This was an attempt to make dialogue more natural and, by denying characters lengthy self-explanation, to show people as unable to verbalize their chaotic feelings. Not surprisingly, characters frequently contradict themselves even from one line to the next. If the amount of dialogue were considerably reduced and interspersed with pauses, the effect would be not unlike Pinter. To make sense of this style the actors must have a very clear notion of what the interior conflicts of a character are that can bring forth such contradictions and yet seem a consistent as a character.

The young actors succeed in this difficult task to varying degrees. Joel Hechter plays Petrell, once in love with Marie, who put him through medical school, but now, seemingly without guilt, he has transferred his affections to the virginal Irene. Hechter makes us believe that Petrell is at once intelligent but also completely unconscious of his opportunism or the hurt he causes. David Jansen brings a Chekhovian quality to the character of Alt, the doctor who can no longer practice, having served time for speeding the death of a suffering patient. His ineffectuality causes the women to mock him as an “old woman”, but his position outside the personal intrigues of the plot gives him alone a sane perspective on the events. But hat is, of course, Bruckner’s point--a sane perspective on chaos can only be ineffectual. The most crucial male role is that of Freder, who cynically plays mindgames with the four women of the play, seemingly for his own amusement. Christopher Morris makes this a chillingly believable character who entices women with flattery and promises of love for the purpose of finding how far he can degrade them. He claims he is merely bringing about the fate these women were destined for, but his enjoyment of the women’s confusion reveals him as an emotional sadist.

Compared to the men’s roles, the women’s are extraordinarily complex. Emblematic of the sickness of youth is Desiree. A member of the now redundant aristocracy, she is filled with a self-loathing thinly veiled by a pose of hauteur and is neurotically obsessed with the lost innocence of childhood. She states that everyone should shoot himself at seventeen to avoid the disappointments to come. Once in love with Freder, she seduces her friend Marie in a series of scenes that in Britain would have been outlawed from the stage until 1967. Fiona Highet is superb in the role. She makes the subtext of Desiree’s contradictory actions clear in every scene by revealing her as someone who seeks vain distractions in life to cover her longing for death. As the boarding-house maid Lucy, Erin MacKinnon, fresh from the George Brown Theatre School, puts in an excellent, finely detailed performance. She makes all too believable how this country girl falls under Freder’s malign influence as he gradually leads her to view her self-worth only so far as she pleases him by discarding her moral scruples.

Unhappily, the remaining two actors do not create a sufficiently strong subtext for their characters to make to make the contradictory manifestations we see credible. The other characters give a clear description of Irene as still a virgin and proud of the superiority she thinks that gives her but unscrupulous enough to enjoy taking Petrell from Marie. Linda Prystawska’s perfunctory line delivery, however, never matches that description or suggests a consciousness of Irene’s duplicity. Anne Page, co-artistic producer of Theatre Voce, has the pivotal role in the play as Marie, whose tidy view of the world is shattered when Petrell, the man she thinks she’ll marry, defects to Irene. Surrounded by Freder’s cynicism and Desiree’s seductiveness, Marie, an embodiment of her lost generation, gradually becomes unhinged and open to anyone with a stronger will--a chillingly prescient metaphor of things to come in Germany. However, while Page is able to communicate the complex emotional throughline of her character, her line readings to be effective require a far greater range of nuance than the uniform vehemence she gives them.

Despite these imperfections, Ed Roy’s imaginative production makes a very strong case not only for this play but for reviving a host of other remarkable plays of the period that have languished too long in obscurity. We should be grateful that a company like Theatre Voce is willing to take such risks to enrich the theatre scene in this city.

©Christopher Hoile

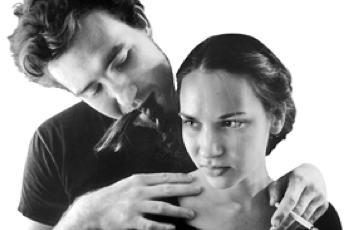

Photo: Christopher Morris and Erin MacKinnon. ©2001 Theatre Voce.

2001-01-26

Pains of Youth