Reviews 2001

✭✭✭✭✩

by Noel Coward, directed by Joseph Ziegler

Soulpepper Theatre Company, Premiere Dance Theatre, Toronto

June 28-July 19, 2001

“Present mirth hath present laughter”. Twelfth Night

Noel Coward is very popular in Ontario this summer with productions of “Private Lives” at Stratford, “Shadow Play” at the Shaw, “Hay Fever” at the Gravenhurst Opera House and “Present Laughter” by Toronto’s Soulpepper Theatre Company. While the other productions are all safely set in the periods Coward specified, Soulpepper, true to its goal of reinvigorating the classics, has given “Present Laughter” a more experimental production which luckily does not compromise the play’s humour.

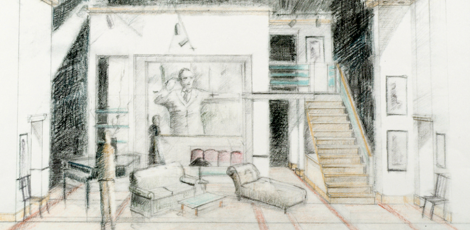

Design is not normally the prime topic for discussion in a play by Coward, but in this case it is. When you enter the Premiere Dance Theatre you can’t help but notice Guido Tondino’s handsome set. The clean lines, the colour scheme of black, white and grey with a touch of natural wood, the rotary phone, the old movie projector suggest that the owner, West End matinée idol Garry Essendine, has bought the latest (for 1939) Bauhaus-influenced flat. But, hold on, there’s a multicoloured Andy Warhol-like print of Juan Chioran (Garry) on the back wall. Maybe this is really supposed to be a modern-day loft. As with the set, so with the costumes and accessories. The valet may wear a bowler, but he has a spiky punk hairdo. Garry’s producer may wear a suit with an Edwardian cut, but he wears sandals, has a pony-tail and carries a cell phone. The obsessed fan, Roland Maule, has laptop and a digital camera.

This is a play where people have servants, where one sails rather than flies to Africa and, indeed, where a person can be enormously famous from acting in plays rather than in television or movies. The play is, after all, Coward’s satire on his life as a celebrity and the introduction of modern devices could seem like intrusions. On the other hand, setting the play firmly in 1939, as in the 1990 Shaw Festival production, risks making the play seem merely like a period comedy with no contemporary significance.

Tondino’s design that makes us ask “Is it now or is it then?” is precisely what director Joseph Ziegler is after. The play may be Coward’s satire on himself but it is also a satire on the cult of celebrity in general. Coward makes clear via the three outsiders to Garry’s “family” of secretary, ex-wife, producer and manager that they see in Garry only what they want to see. The mad fan Roland, the star-struck debutante Daphne and his producer’s wife Joanna all claim that they are the only ones who see and appreciate the “real” Garry Essendine.

This is all the more ironic since Coward also clearly shows that there may not be a real Garry Essendine. He is a performer both on and off the stage so that it is impossible to tell when he is acting and when he is not. Since Coward generalizes this theme to include all the other characters, the play, especially when not presented as a period piece, become a critique of the nature of personality. Ibsen’s “Peer Gynt”, mentioned twice in the play, contains the famous onion metaphor that could apply to all of the characters—we are merely a series of layers but have no core. Such depths, not just the surface wit, are what make Coward’s plays last.

Ziegler and his cast fully bring out both the wit and what lies behind it to make this both an hilarious and intellectually stimulating evening of theatre. He has given the play a perfect pace so that seemingly haphazard incidents gradually crystallize into structure and the humour builds and builds until the riotous final scene. He makes us see, before it is said, that this seemingly realistic glimpse into the life of a star actually takes shape as that most theatrical of genres--the French farce.

The cast is excellent. Juan Chioran, in his first appearance with Soulpepper, plays Garry as someone whose life is so theatrical the mask has stuck. Even he can’t tell when his emotion are real or not. For a character who mostly indulges in a series of tantrums, Chioran does not make the mistake of starting out too big, but rather always keeps something in reserve for general brouhaha of the ending. Chioran’s character is always “on” leaving us wanting to have a glimpse of the real Garry. But that is the point.

If Garry is selfless in a literal sense, his ex-wife Liz is selfless in a figurative sense. As played by Martha Burns, she is the calm centre of Garry’s life, the stage manager of the convoluted plots he gets himself into who can rewrite them to have a happy ending. Nancy Palk shows that Monica, Garry’s faithful secretary, gives him the logic and efficiency he himself lacks, and lets us see the suppressed love underneath the stiff exterior. Patricia Fagan gives her best performance yet for Soulpepper as the calculating Daphne. Brenda Robins is magnetizing as the equally calculating but mature Joanna and manages to exude sensuality despite the dreadful frock Tondino has designed for her.

Rick Miller lends the obsessed fan-from-hell Roland an upsetting, dangerous edge that well suits this 21st-century vision of the play. Michael Hanrahan gives us a confident, materialistic Henry (Joanna’s husband) and Neil Foster a tortured Morris (who is having an affair with Joanna). In lesser roles, Joyce Campion, Garry’s Swedish spiritualist maid, can get a laugh merely through her deliberate walk and dialect-distorted vowels. Allan Hawco gives a assured performance as Garry’s jaunty, no-nonsense valet—quite a stretch from the melancholy prince in “The Triumph of Love” just last month. Charmion King is delightful as Lady Saltburn, the unsuspecting mother of the errant Daphne.

Guido Tondino’s costumes (except for Joanna’s) are attractive and give the sense of the 1930s as reinterpreted in 2001. Louise Guinand provides the kind of lighting that is so natural one completely forgets that primary light sources are not the ones on stage.

There is no doubt that most people would prefer their Noel Coward the old-fashioned way. We’ve been trained to think of his works as light, witty comedies and nothing more. Soulpepper’s experiment of keeping us off-balance as to the period of the action proves that a play that provokes laughter can also provoke thought. I am certain that this kind of experiment with 20th-century drama will only become more common the further we move away from that century. At its best Soulpepper, as in this production, dusts off the classics and makes them seem brand new.

©Christopher Hoile

Photo: Set design for Present Laughter. ©2001 Guido Tondino.

2001-07-22

Present Laughter