Reviews 2001

✭✩✩✩✩

by Anton Chekhov, directed by Diana Leblanc

Stratford Festival, Avon Theatre, Stratford

August 14-November 3, 2001

“The Dead Duck”

Diana Leblanc has directed some of the finest productions in the history of the Stratford Festival, most notable "Long Day's Journey into Night" in 1994 and "Death of a Salesman" in 1997. She has also directed one of its most notable bombs--the "Macbeth" of 1999. "The Seagull", I am sorry to say, falls into the latter category.

"The Seagull" (1896) is the first of Anton Chekhov's four great masterpieces that have had a profound influence on modern drama. They attempt to reproduce the way people actually speak leaving more left unsaid than said. They forego standard plots and substitute for action conversational variations on a particular theme. And they are written not for stars but for an ensemble of actors. For a Chekhov play to work every part, no matter how small, must be as well-played as the larger parts or the careful pattern the author has constructed will fall apart.

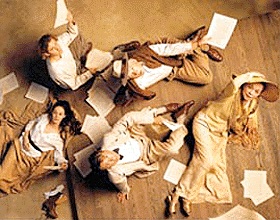

Unlike the Shaw Festival, Stratford from its very beginning has been built on a star system, not an ensemble system, which means that a director of Chekhov at Stratford has to have especially firm control over the actors in order for the play to cohere and for its themes to come across clearly. Leblanc's main failing is to provide seemingly no control whatever. As a result the theme in this the most diffuse of Chekhov's four masterpieces is completely lost and the play devolves into a series of unconnected star turns. This plus an ill-conceived design concept and poor acting from the couple who are the story's focus make "The Seagull" a must-miss in the current season.

As usual for Chekhov the play is set in a manor in the Russian countryside where a varied group of people attempts unsuccessfully to combat the boredom of country life. Chekhov is particularly interested in the self-deceptions people practice in order to convince themselves to go on with life. Despite its tragic ending, Chekhov labelled the play a comedy because of the series of unrequited love affairs that unite the principal characters. The schoolteacher Medvedenko loves Masha who loves the would-be writer Konstantin who loves the would-be actress Nina who loves the well-known writer Trigorin who falls in love with her but can't break from the hold of the well-known, self-centred actress Irina Arkadina. The comedy is man's ability to desire what he cannot attain and focusses on the young central couple who feel both jealous of and suffocated by the older generation. The comments of a doctor, Irina's elderly brother and various servants provide differing perspectives on how to live in the midst of failure.

Leblanc has not been able to draw from the cast the consistent acting style so necessary in an ensemble play. Martha Henry (Irina) gives us excerpts of a number of past roles without giving her character a coherent personality. Rod Beattie (the doctor Dorn) has not been able to expunge Walt Wingfield from his delivery or manner. Brian Bedford (Irina's brother Sorin) does at least attempt to play an aged gentleman, but one can still notice his familiar routines behind the long beard and within his confines his wheelchair. By contrast, Lally Cadeau (Masha's mother), Brian Tree (the groundskeeper Shamraev) and Peter Donaldson (Trigorin), alone among the senior cast members, create individual characters whose roles serve the whole of the play instead of standing out from it.

Leblanc starts the play on the wrong foot by having Sarah Dodd (Masha) deliver her famous line "I'm mourning for my life" as if it were a joke rather than the serious statement it proves to be. From then on Dodd's presentation of this character is never clear. Aaron Franks (Medvedenko) seems pretty much a nonentity. Worst of all are Michael Therriault (Konstantin) and Michelle Giroux (Nina) who represent the unappreciated younger generation. Their actions affect the actions of all the other characters and their frustrations are the throughline of the play. Unfortunately, neither actor is up to the part. Konstantin is torn between his desire to gain the favour of the older generation and to rebel against them. Therriault's performance is merely bluster and confusion. Nina is frequently compared to a seagull ever drawn to the lake and so can be considered the title character. But Giroux's performance is a disaster on every count. Her delivery and gestures are no different from what she does as Olivia in "Twelfth Night" or Griselda in "Tempest-Tost". Chekhov constantly demands that characters show thoughts and emotions beneath the often banal surface of what they say. This is totally beyond Giroux, who in Nina's all-important final scene with Konstantin, abruptly shifts from happiness to despair to resignation, illustrating the text on a line per line basis but never discovering its overall meaning. When she speaks of the horror she feels when giving a poor performance on the stage, a palpable ripple of embarrassment coursed through the audience with just such an example before them.

The presence of actors and authors and the performance of Konstantin's symbolist play in Act 1 must have given Leblanc and designer Astrid Janson the notion of staging the play as if it took place now in a rehearsal hall. We have a plain wooden set surrounded in back with horizontally suspended layers of blue cloth, meant, I suppose, to suggest the sky and lake we hear of so often. Janson hasn't solved the transition from Act 3 to 4 and so has doors in their jambs set up in Act 3 where the cast walks through the absent walls to go downstage, while in Act 4 they suddenly function as doors. The costumes are all contemporary with the slightest hint in their cut of the 19th century, though many will wonder why a serving girl is wearing red basketball shoes. Louise Guinand's lighting has created a beautifully dreamy atmosphere that the rest of the production itself never lives up to.

This is a production that will convert no one to Chekhov. With its incredibly weak direction and its poor performances, this lyrical play seems merely boring and pointless. Anyone lucky enough to have seen Neil Munro's exciting production for the Shaw festival in 1997, with Ben Carlson as Konstantin and Jan Alexandra Smith in a riveting performance as Nina, will know how gripping and moving this play can be. The present production will make most people want to move to the nearest available exit.

Photo: Michelle Giroux, Michael Therriault, Brian Bedford, Peter Donaldson and Martha Henry. ©2001 Chris Nichols.

2001-08-16

The Seagull