Reviews 2002

✭✭✭✩✩

by Larry Tremblay, directed by Kevin Orr

Odonata and Solar Stage, Factory Studio Theatre, Toronto

January 9-27, 2002

"Maudit Anglais"

"The Dragonfly of Chicoutimi" is a play in English by a French-speaking Québecois playwright. If that were not odd enough, playwright Larry Tremblay has deliberately written the play so that it sounds like a literal translation from French, adhering closely to French grammar and sentence structure and often using English cognates for French words. The point of this exercise is to present us with a twofold mystery: What really happened when our narrator was a boy that still haunts him? And why is he speaking for the first time in his life in a foreign language? The questions are potentially intriguing but despite the best efforts of all concerned the play is never fully engaging and its subtext rather more simplistic than mysterious.

"Dragonfly" had its première at Montreal's Festival de Théâtre des Amériques in 1995 presented by the Théâtre d'Aujourdui. Despite the company's apprehension about presenting a play in English as a French play, it became the most successful production in that company's history and went on to tour parts of North America and Europe. Odonata and Solar Stage in association with Factory Theatre are now giving the work its belated Toronto première.

The sole person in the play is Gaston Talbot, a soft-spoken man in his late 50s and native of Chicoutimi, Quebec. Although the fact has been mentioned in preliminary news articles about "Dragonfly", we do not learn until the very end that until now Gaston has not spoken for 40 years. Speaking in a halting, childlike way, Gaston initially tries to pass himself off as a man of the world with a vision to communicate. "Keep in touch" is his motto. Soon enough he reveals this as a lie. He has never been outside of Chicoutimi--all the more wonder then that he should have had a series of nightmares in English, a language he does not know. In the course of relating these dreams it becomes clear that Gaston is haunted by an incident in his past. While playing cowboys and Indians with his twelve-year-old friend Pierre Gagnon near his "rivière aux roches", Pierre died. Was he murdered or was it an accident?

There have been rather too many plays and films recently, like Michel Marc Bouchard's "Down Dangerous Passes Road" that played in this same venue just two months ago, for us to be very curious about the answer. After all, why should Gaston still be haunted by the death if he were not in some way involved? The more interesting question is why Gaston is speaking in such a bizarre fashion. A monolingual French-speaker suddenly speaking in English is one component, but we also wonder why this middle-aged man is speaking as if he were a child and why is it he is so given to lying to us about himself.

Unfortunately, the answer to these questions is that Tremblay, like Bouchard in "Passes", is presenting us with an allegory not a real character. Written as if to please academics riding the current vogue of post-colonial studies, Tremblay presents English as the language of the oppressor and French as the language of the oppressed. While French is the language of nature ("rivière aux roches") and song ("Tout va très bien" and "J'attends le jour"), English is the language of Gaston's nightmares and Pierre's sadistic commands. Tremblay has Gaston label the English language as "shit" and to demonstrate how unattractive it is he has Gaston utter a series of English words, like "popsicle sticks", emphasizing their consonant clusters. Needless to say, this sort of dichotomy may go over with some French-speaking audiences, but it will hardly wash with English-speakers or anyone who realizes that a language's supposed beauty or harshness is subjective. More troubling is the parallel Tremblay suggests between French-speakers and "Indians" as if the two were somehow equally oppressed by English-speakers and as if French-speakers did not also share in oppressing native peoples.

What emerges is a play overflowing with a self-hatred that is unpleasant and unenlightening. Gaston speaks in the nightmare language that guilt has imposed on him. He feels like a dragonfly pinned down in his uncle's insect collection.

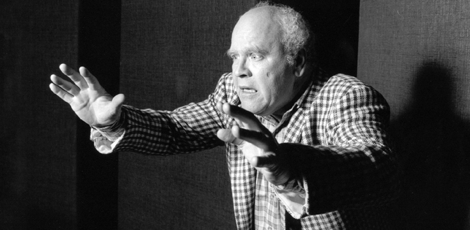

Bilingual actor Dennis O'Connor is an ideal choice to play such a linguistically challenging part. He does as much as possible to humanize the allegory, to differentiate the Gaston of the present from his mother and past self and to bring out the wrenching emotions of the story. O'Connor's performance is in perfect accord with what we learn about Gaston at the very end of the play, but until that time it is hard to decide whether the child-like delivery and emphasis on plosives and sibilants is an affectation or part of the character. Gaston lies to make himself seem better than he is, but by presenting him thus, Tremblay makes it difficult for us get involved with a story so subject to contradiction.

Director Kevin Orr has emphasized the emotions in the play to the extent that Gaston never appears to be free of an agonizing inner turmoil. Yesim Tosuner's minimalist set consists of only a chair and table on a dais in front of three rust-coloured fabric panels. Orr has tried to bring out the aspect of the play-as-theatre by having O'Connor play the first third of the 80-minute show with lights up on the audience level, gradually moving onto the stage and finally seating himself in the chair as if Gaston gradually shifted from an ordinary person entering from the theatre's side door to a character in a play. Unfortunately, this has the undesired effect of paralleling our growing disinterest in our untrustworthy narrator. Steven Hawkins's lighting consists entirely of a beautifully managed gradual fade from the lights up at the beginning to light only on O'Connor's face at the end in the midst of darkness.

Students of Canadian drama will likely want to see this forceful if over-schematic expression of Québecois alienation. Factory Theatre Artistic Director Ken Gass has said he does not think of the play as "anti-English", but I think that is exactly how most theatre-goers will take it. Even if this were not the case, most people will not look charitably on such an unmitigated dose of self-loathing that blends two languages for divisive ends.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: Dennis O’Connor as Gaston Talbot. ©2002 David Hawe.

2002-01-10

The Dragonfly of Chicoutimi