Reviews 2007

✭✭✭✩✩

by John Steinbeck, directed by Martha Henry

Stratford Festival, Tom Patterson Theatre, Stratford

June 21-September 22, 2007

"The Best-Laid Schemes ... Gang Aft Agley"

Stratford’s first-ever staging of John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men” (1937) is a so-so production of a play that ought to be vital and heartbreaking. Anyone who saw the fine Theatre Calgary/CanStage coproduction directed by Dennis Garnhum last year will know this. What hinders the Stratford production’s effectiveness is a combination of uninventive direction, poor use of the Tom Patterson stage and an uneven cast.

The story follows two itinerant farmhands, the quick-witted George and the mentally “slow” companion as they seek work in Depression-era California and dream of sometime having their own place where they are their own bosses. The farm where they find work is itself filled with misfits who cope with loneliness and unfulfilled dreams in ways ranging from acquiescence to violence.

The main challenge to a director is that the work is fundamentally static. Other static plays like “Long Day’s Journey into Night” move forward on the revelations of past secrets that inform the present. “Of Mice and Men” simply moves forward through time as we wait for the play’s combustible elements to come into contact. Steinbeck creates more tension through the heavy use of prefiguring rather than through the dynamics of conversation. One aspect of the play’s modernity, its naturalistic, intentionally repetitive dialogue, is also a source of its stasis.

The trick for a director is to emphasize the tension in the play while avoiding any sense of melodrama or sentimentality. Director Martha Henry does seem intent on avoiding melodrama but does so by only by downplaying what little tension and dynamism exist. The physical staging is the first problem. The play is clearly intended for a proscenium stage not a runway thrust stage like the Tom Patterson stage. If one is going to use such a stage one should use it fully. Designer John Pennoyer has divided the stage into two. The downstage half represents George and Lenny’s camp the first scene and their meeting place in the last. The upstage half represents the bunkhouse of the farm where the two find work with the bunks themselves most underneath the balcony. The obvious problem is that Henry thus crams two-thirds of the action into only the upstage half of the stage. This not only restricts the area for physical movement on stage but forces anyone sitting in side sections facing the front half of the stage to sit sideways in their seats for most of the play.

Besides this, Henry stages a key moment, when Lenny crushes the hand of the young farm owner Curley, among the bunks under the balcony so that no one, not even those on stage can clearly see what has happened. It is crucial that this event be seen by all because it proves to the ranch hands how powerful and dangerous Lenny’s brute strength is. They need this knowledge to leap to the conclusion in Act 2 that Lenny has murdered Curley’s wife. Henry also curiously downplays the tension in other important scenes. Why have the old man Candy lie down on his bed, his face away from the audience, while his dog is taken out to be shot. We would like to know his reaction. In the Theatre Calgary production this scene was filled with an almost unbearable tension. Here no one on stage even jumps when the shot finally comes.

In the Theatre Calgary production the actors knew how to move and talk like ranch hands. In the Stratford production only some know how to do this convincingly. As George, Nicolas Van Burek has considerably toned down his usually overheated style. Even so, he allows himself wide gestures with arms and hands that are too theatrical for a naturalistic character, especially a ranch hand. George is supposed to be a cool, rational character, but Van Burek makes him come off as a hothead. As Lenny, Graham Greene captures the childlike nature of the character at some points, encouraged by Henry, into being rather too cutesy. What is missing is the sense of uncontrollable strength and an underlying rage born of frustration that should also make George clearly appear dangerous.

The four who have the best handle on their characters are Jerry Franken as Candy, Stephen Russell as Slim, Philip Akin as Crooks and Brad Rudy as the Boss. They each have the kind of deliberate movements and unemphatic manner of speech of men whose unrewarding work has driven the hope out of them. Russell in particular gives one of his best ever performances and justifies his role as the moral centre of the piece. One wishes he were cast more often in 20th-century works. Franken is also excellent as broken-down old man clutching at anything that will give him a reason to live.

On the other hand, Brian Hamman does not conjure up enough neurotic menace as Curley and Robert King does not communicate enough mean-spiritedness as the dog-hating Carlson. As youngest hand Whit, Aidan deSalaiz seems to have popped in from “Degrassi Junior High” rather than anywhere in the sticks in the 1930s. On the evening I saw the play Tova Smith substituted for Jennifer Mawhinney in the role of Curley’s wife. Given that her interpretation of the role was all wrong, blame has to put down to Henry’s direction. All the farm hands call Curley’s wife a tart but that doesn’t mean they are right. By having Curley’s wife constantly caressing herself and hitching her dress up when she speaks to the men, Henry leads us to think the poor woman is a nymphomaniac. In fact, as is clear from everything she says, she is extremely lonely and is only seeking someone to talk to since her husband is both insanely jealous and never at home. In her finally speech in the hayloft to Lenny, it should be obvious that she is painfully naive and, in accordance with the play’s imagery, as much of an innocent as Lenny’s mouse or puppy. Henry’s odd approach puts us out of sympathy with her and severely skews the arc of the action.

Bonnie Beecher is normally a magician with lighting, but in this production, except for the scene in Crooks’ room, she strangely keeps the lights at the same drowsily dim level throughout. To create a sense of place Henry relies more on Todd Charlton’s amazingly detailed soundscape. The problem is that it is often too loud and calls attention to itself.

Those who have never seen the play before will probably be satisfied with the Stratford production though even they may wonder why the play seems listless. For those who have seen a superior production, the reasons for this lack of impact will be clear. In either case Stratford’s “Of Mice and Men” is not the compelling piece of theatre it ought to be.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

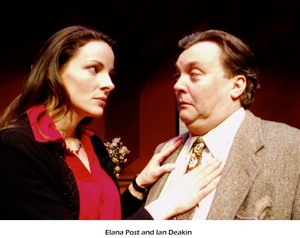

Photo: Graham Greene and Nicolas Van Burek. ©2007 David Hou.

2007-07-24

Of Mice and Men