Reviews 2007

✭✭✩✩✩

by Derek Walcott, directed by Peter Hinton

Stratford Festival, Studio Theatre, Stratford

August 8-September 28, 2007

“Journey to Nowhere”

People who think they might like to Stratford’s current production of “The Odyssey” should make sure to read Homer’s epic and perhaps a handbook of Greek mythology before attending the show. Playwright Derek Walcott assumes the audience is so intimately familiar with Homer’s work that they will be able to appreciate his changes to it. That’s fine but director Peter Hinton ensures that the story is so confusingly presented that even those who know the story will have trouble figuring out what’s going on.

In 1992, the same year in which Trinidadian poet Walcott was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, the Royal Shakespeare Company presented Walcott’s stage adaptation of “The Odyssey” in Stratford-upon-Avon. Walcott is best known for numerous books of poetry and his great epic poem “Omeros” (1990) not for his few plays. The reason for this is quite evident in “The Odyssey”. It overflows with characters speaking verse to each other but is not actually dramatic.

Homer’s “Odyssey” is both narrative and episodic. Simply staging a series of episodes from the poem does not create dramatic tension. In fact, though people tend to think of “The Odyssey” as an adventure story, the poem is just as much about delay and waiting. Odysseus has already been away from his home in Ithaca for ten years while fighting in the Trojan War. After leaving Troy, Odysseus and his men are blown off course by storms. They receive a gift from the wind-god Aeolus, but Odysseus’ men, thinking it is treasure, open it and they are swept away even further away from home. It takes Odysseus ten more years to return. Meanwhile, his wife Penelope is besieged by one hundred suitors who try to convince her that Odysseus is dead and that she should remarry. When they threaten to kill her son Telemachus he flees to safety. Penelope says she will remarry only when she is finished weaving a shroud but every night she unravels what she weaves to buy time as she waits for her husband’s return.

Walcott’s adaptation is highly literary. Characters usually appear without introduction so that we often have to guess who they are. Unless you know your mythology you will not know that the old man in drag in the Underworld speaking to Odysseus is the prophet Tiresias because the name is never mentioned. Walcott also sometimes refers to characters by their epithets alone, so that you will have to know that the “grey-eyed goddess” is Athena because Walcott doesn’t tell you. You will also have to know that Hyperion and Apollo are the same god, not different ones. To add to the confusion the goddess Athena takes on three different guises, two of them male. The Homer-like narrator Blind Billy Blue stays in the same costume but is referred to by different names since he stands in for any singer in a land Odysseus visits. Besides this, all the actors except for Nigel Shawn Williams who plays Odysseus take on anywhere from two to four roles. In Hinton’s production it is not always clear when an actor takes on a new role versus when a character takes on a new disguise. It would help if costume designer Katherine Lubienski clearly distinguished the actors’ various roles but she does not. It helps that all of Penelope’s suitors wear tuxes, but as Odysseus’ crew they all have individualized costumes of historical periods ancient to modern so that when we meet these actors later in different costumes we don’t immediately know whether they are crew members or new characters.

Hinton’s unfocussed direction exacerbates the confusion. First of all, he doesn’t seem to have decided whether he is presenting the work in a universal or specific setting. It would make sense given Walcott’s background to set the play in the Caribbean. Under Hinton, sometimes it is, sometimes not. Some actors use Jamaican accents throughout (as if that were the only Caribbean accent), some like Odysseus do not and some switch back and forth with no clear reason why. The confusing costume design reinforces the impression of sloppy direction. The Phaeacians are clearly contemporary Caribbeans, but the islands of the Cyclops and of Circe are excursions into cheesy science fiction. The Underworld seems to have become the London Underground, while in Ithaca the women, except for Odysseus’s Jamaican nurse, wear classical Greek tunics and the men modern formalwear. “Why is Athena dressed as a Western cowboy when she is supposed to be a “shepherd”?” is only one of innumerable such questions that arise.

Hinton occasionally decides to “improve” Walcott’s text. In the original Walcott manages Odysseus’ slaying of the one hundred suitors with a stage direction. Not Hinton--he actually counts off and names all one hundred as each is slain while Odysseus, Telemachus and Eumaeus have to mime both shooting the deadly arrows and being struck down by them as suitors. It’s hard to imagine a more foolish or tedious addition to a play that is already three hours long.

Not only this, Carolyn M. Smith’s set is a disaster. Whether the play is set in the Greek islands or in the Caribbean, all the travel referred to is by boat. Why then does a burnt-out car occupy the stage throughout the show so that when Odysseus’ crew sail from one island to another they have to sit on top of the car and mime rowing? Only once when Telemachus needs a “chariot” is the car used as a car. Not only is it thoroughly inappropriate but it also severely limits the use of the stage space. It is equipped with a mast and but the “sail” on it is never unfurled during Odysseus’ travels. It is only unrolled when it represents Penelope’s shroud. Why miss the opportunity to parallel the two? Then, at the very end, when you think the show’s imagery could be not more confounded, the shroud is revealed to be the Canadian flag! The show has the effect of taking a handful of contraindicated medicines in the hopes at least one will work.

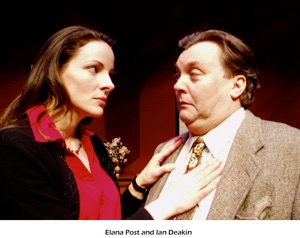

Hinton’s direction consistently emphasizes the visual over the verbal, but Robert Thomson striking lighting and use of a wide range of gobos is the only consistently successful visual element. Otherwise, the design is incoherent the underrehearsed verbal side is not there for support. Walcott’s poetry is wonderfully rich and muscular, but very few of the actors are able to make it sound natural much less beautiful or even to have it make sense. Fortunately, Nigel Shawn Williams who plays Odysseus is one of those few. He revels in Walcott’s mouth-filling words and clearly depicts Odysseus ageing and growth in insight through his long travails. Jeremiah Sparks as Blind Billy Blue is also always easy to understand although all his lines are sung and vowels lengthened with melismas. Walter Borden as Eumaeus, a Philosopher and Tiresias also has a good handle on Walcott’s language. Among the women Barbara Barnes-Hopkins speaking a consistent Jamaican patois as Odysseus’ nurse Eurycleia is always a pleasure as is Joyce Campion as Odysseus’ British-accented mother Anticlea.

Allegra Fulton gives a moving performance as Penelope and is a satirically slinky Helen, but as Circe she unsuccessfully attempts a Jamaican accent that obscures all she says. In-Surp Choi delivers his lines as Telemachus with enthusiasm and vigour but not always with the clearest diction. This becomes worse when he, too, attempts a Jamaican accent as Odysseus crewmate Elpenor. Jennifer Morehouse has the important role as Odysseus’ divine protector Athena, but she doesn’t have sufficient vocal heft to make a convincing goddess. (It doesn’t help that her oversized helmet crest makes her look ridiculous.) Sophia Walker is an enticing Nausicaa and a sullen Melantho. Steve Ross is the most consistently articulate of Odysseus crewmen.

It is praiseworthy for Stratford finally to delve into the world of Caribbean literature, but how much better it would be if “The Odyssey” had been staged by a creative team whose goal was to communicate the work as clearly and effectively as possible rather than becoming ensnared in a series self-satisfied quirks of design and direction. The production is so confused it seems determined to frustrate any enjoyment of Homer or Walcott.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: Nigel Shawn Williams. ©David Hou.

2007-08-30

The Odyssey