Reviews 2007

✭✭✭✭✩

by Paul Sportelli & Jay Turvey, directed by Eda Holmes

Shaw Festival, Court House Theatre, Niagara-on-the-Lake

July 28-October 6, 2007

"An Exquisite New Musical"

Anyone who has despaired about the state of the musical in general or of the Canadian musical in particular should head down to the Shaw Festival to see a show that will restore your faith in both. “Tristan” by Paul Sportelli and Jay Turvey, currently in its world premiere run, is a lovely gem of a musical, beautifully crafted and beautifully presented. At a time when musicals seem to be either parodies based on bad movies or stitched together from rock groups’ back catalogues, it is a relief to find a musical that deals with a complex subject with equally complex but gorgeous music of many moods.

Sportelli and Turvey take their story from the German novella “Tristan” by Thomas Mann first published in 1903. Heinrich Kloterjahn, a businessman from the Baltic port of Rostock, brings his young wife Gabrielle to Einfried, a sanatorium in the German Alps, in hopes of a cure for diagnosed disease of the trachea. There she joins in the strict regimen of the eccentric inhabitants. In particular, she is drawn to a handsome young writer Detlev Spinell, who is not ill but is oddly moody. He, in turn, falls madly in love with Gabrielle but doesn’t know how to deal with his feelings. Though their own regard for propriety and the ceaseless surveillance of others keeps them at a distance, Spinell finds that a love of music unites them and he begins a projects to release the creative soul in Gabrielle that he feels has been stifled by her bourgeois life as a wife and mother.

The themes of art and love find echoes among Einfried’s inhabitants. Fräulein von Osterloh, the sanatorium’s nurse and general factotum, longs for the attention of Dr. Leander. A Russian couple, the painter Natalia Brodyagina and her husband Vladimir, live a bohemian life that happily weds both love and art. Even a philistine busybody like Frau Spatz has her needlework, and the mysteriously silent Frau Hohlenrauch will occasionally break into song or dance. At the same time, the elderly General is a reminder of an unhappy life devoted to duty alone.

The climax of the piece comes when Spinell encourages Gabrielle to play the “Liebestod” from Wagner’s opera “Tristan und Isolde” on the piano and both are transformed by the ecstasy of the music. To some it may seem a problem that the climax of a musical should focus on music from an opera, but such an objection ignores Thomas Mann’s goal in the novella. One could easily ask why Mann would write a novella set in his own period that refers back to the famous medieval epic by Gottfried von Strassburg hat was also the source for Wagner’s opera. As in his novel “Dr. Faustus”, Mann is interested in uncovering the survival of mythic structures in contemporary life. One could say that Sportelli and Turvey have chosen just the right genre; just as Mann’s modern novella is to the medieval epic, so is this modern musical to Wagner’s opera.

In any case, Sportelli and Turvey’s musical language is so sophisticated, especially when involving Gabrielle and Spinell, that the transitions into and out of the Wagner passage is masterfully done and Wagner’s “Tristan” motifs serve as “leitmotifs” in the musical itself. Just as the two lovers feel separate from the other inhabitants of Einfried, so the long soaring lines of their songs like Spinell’s “One Face” in Act 1 or Gabrielle’s “Isn’t It Strange?” in Act 2 contrast with the generally jaunty tunes of the others. The group’s introductory song “Einfried” and the following gossipy number “I Heard” are very much in the style of Gilbert and Sullivan with witty polysyllabic rhymes to match. Sportelli and Turvey reflect Mann’s point that a grand passion can arise in the midst of ordinary even comical surroundings.

It’s possible that the production would be stronger if the cast was composed entirely of fine singers, but that might not reflect so well the contrast of the extraordinary with the ordinary. One blessing of the production is that no one is miked. Glynis Ranney and Jeff Madden give wonderfully focussed performances as Gabrielle and Spinell. Both are characters much more complex than one ordinarily finds in musicals. Gabrielle appears fragile when we first meet her, but gradually Ranney shows how she gains in physical strength through interaction with others at Einfried and how she begins to glow with passion under Spinell’s influence. Madden is superb as Spinell. He maintains the ambiguity of the character, someone who doesn’t fit in and whose project of liberating Gabrielle’s creativity is not completely altruistic. Nevertheless, he, too, is a kind of innocent who doesn’t really understand the ways of the world. Madden’s singing of the musical’s most excerptable song “One Face” is hauntingly powerful.

To maintain balance in the piece, the role of Gabrielle’s husband Heinrich is given to Mark Uhre, a singer with an operatic voice and full ringing tone. His introductory song “My Life” bespeaks the strength and power of a life of work, so unlike the artificial world of the “rest cure” at Einfried. To some extent Sportelli and Turvey side with Spinell in viewing Heinrich as the villain of the piece because of his narrow views when, in fact, it should be clear that he loves Gabrielle so much he has sought out the best treatment for her. The musical should really show the conflict between realism and idealism as more evenly balanced.

Patty Jamieson paints a comic but sympathetic portrait of the devoted but over-worked Fräulein von Osterloh. Graeme Somerville is no singer but has the right authoritative demeanour for Doctor Leander and copes as well as he can with the music. Donna Belleville is a finely comic Frau Spatz and her non-singer’s voice suits the character. As the General, Neil Barclay sings very well and makes his character’s short song “Happy” quite moving. Gabrielle Jones, a singer, and Peter Millard, a non-singer, are well paired as the life- and art-loving Russian couple. Jane Johanson, who is primarily a dancer, has the unusual ability to make the mostly silent Frau Hohlenrauch an unforgettably intense presence.

The Festival has in no way stinted on the production. William Schmuck’s costumes especially for the women are well conceived as indications of character from the restrictive drabness of Frau Hohlenrauch to the overelaborate lushness of the Natatia Brodyagina. Judith Bowden has created a highly imaginative set that under Kevin Lamotte’s magical lighting conjures up a world of ice and snow through whites and greys and steel. Particularly effective is the use of lucite for the back columns, a candelabrum and the piano. The latter two light up from within lending an otherworldly sense to the piece’s musical climax when Gabrielle plays Wagner for Spinell. Eda Holmes’s direction easily shifts between comic and serious moods and subtly builds up tension as the work progresses. It is very wise of her to abandon realism altogether in the climactic Wagner scene to focus our attention on the psychological effect of the music on Gabrielle and Spinell.

The absolute commitment of the actors and musicians to the piece shines through at every moment. Here, at last, is a new Canadian musical worthy to be ranked with the best works of the post-Sondheim generation. This is a real triumph for Sportelli and Turvey and for the Shaw Festival that commissioned and nurtured it.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

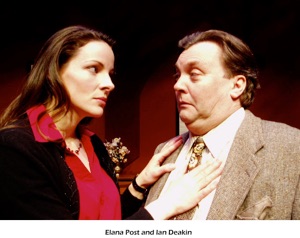

Photo: Neil Barclay, Glynis Ranney, Graeme Somerville, Patty Jamieson,

Donna Belleville, Jeff Madden, Jane Johanson, Krista Colosimo. ©David Cooper.

2007-08-30

Tristan