Reviews 2008

✭✭✩✩✩

by William Shakespeare, directed by Michael Langham

Stratford Festival, Tom Patterson Theatre, Stratford

May 31-October 4, 2008

"O, they have lived long on the alms-basket of words" (V, i)

The Stratford Festival’s current production of Shakespeare’s early comedy Love’s Labours Lost is meant to showcase the talents of the Festival’s Birmingham Conservatory for Classical Theatre. That is a worthy endeavour in itself and recalls the time when Stratford’s Young Company was given its own show. But, in this case, it is also the production’s greatest weakness. The wordy, nearly actionless play is difficult to bring off at the best of times and here it so happens that none of the best performances come from the Conservatory students.

The play is difficult because it is a satire of intellectualism. That man can use reason to keep his desires in check is part of what makes man human. Yet to deny desire entirely is also to deny part of our humanness. This extreme is found in both the main plot and subplot. In the main plot the King of Navarre and three friends vow to devote themselves to three years of study and to shun the society of women. It so happens that King had previously given permission for the Princess of France to visit. When she arrives with three of her friends, the King agrees to deal with the state matters they have in common but refuses to allow the ladies to lodge in the palace. In the geometrical way the plot works out there’s no surprise that the four men soon one by one break their oath and fall in love with the visiting ladies. In the subplot we find a comic rivalry between the fanciful, Don Quixote-like Don Adriano de Armado and the earthy peasant Costard for the love of the country wench Jaquenetta. Related to the theme of mind versus heart is that of words versus meaning in which vows and euphemisms through which Shakespeare satirizes the difficulties mankind creates for itself in trying to control and embellish ordinary reality. At the very end of the play unembellished reality suddenly impinges on the world of the play to reveal the word-play of all the characters for the vanity it is.

In this handsome but fairly dozy production it is really only the subplot that holds our attention. Peter Donaldson gives a wonderful performance as Don Armado. Some actors make the eccentric Spanish gentleman so fantastical that he seems barely human. Not so with Donaldson who makes sure we see that this observer of peculiar protocols and lover of odd words and circumlocutions is still a flesh-and-blood character. As his page Moth, Abigail Winter-Culliford is a constant delight and the best Moth I have ever seen. Though only twelve, she speaks her lines more clearly and with greater understanding than do the Conservatory students. At last, the duel of wits between Moth and Don Armado is an equal one and becomes the highlight of the show. The ever-dependable Brian Tree is an excellent Costard, slowly moving toward the breaking point in constantly having to humour the word-mad intellectuals around him. John Vickery uses the same sort of pompous line delivery he did as Capulet in “Romeo and Juliet” except that here as the supercilious Schoolmaster Holofernes it is more appropriate. Gareth Potter as his foil the curate Nathaniel is virtually unrecognizable beneath his whiskers and plays the ancient man convincingly. David Collins, also hidden beneath a pile of facial hair, is a reliable Constable Dull. Stephen Sutcliffe is a superficial but charming Boyet.

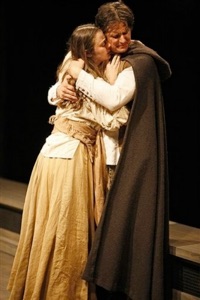

Seven Conservatory students (plus Michelle Monteith) play the four pairs of lovers: Dalal Badr (Rosaline), Jon de Leon (Dumaine), Jesse Aaron Dwyre (Longaville), Alana Hawley (Princess of France), Melanie Keller (Maria), Ian Lake (Berowne), Michelle Monteith (Katharine) and Trent Pardy (King of Navarre). They are all word-perfect, speak clearly and move gracefully about the stage. The problem is that they don’t create distinctive personalities and don’t seem to have moved beyond conning their lines to interpreting them. In a play where the matched sets of four already seem interchangeable and where action is replaced by verbal sparring, this a crucial flaw and dulls the evening. The best is Dalal Badr who has real stage presence a sense of spritely wit that show us she is the perfect companion for the rebellious Berowne. It is rather too bad, then, that Ian Lake’s Berowne does not match her Rosaline since his role, which includes the longest speech in Shakespeare, is the juiciest. Lake’s diction is the least clear of the four men and he he doesn’t point his speeches precisely enough to make their wit manifest. The eighth current Conservatory student in the show is Stacie Steadman as the milkmaid Jaquenetta, but she has little to do but look perplexed at Don Armado’s convoluted attentions.

Designer Charlotte Dean has created in the Tom Patterson Theatre a miniature version of Tanya Moiseiwitsch’s stage for the Festival Theatre. It is so simply, practical and aesthetically pleasing it makes one wonder again why none of the three productions now open at the Festival Theatre has seen fit to use it. Moiseiwitsch’s stage is meant to obviate the need for “scenery” and thus to place emphasis on the actors, precisely what the massive sets used by Des McAnuff in “Romeo and Juliet” and Peter Hinton in “The Taming of the Shrew” do not do. Dean’s has shifted the setting forward from the sixteenth to the seventeenth century giving the men the pantaloons, doublets and lace collars and cuffs that rather make them look like the Four Musketeers. The women are in lovely pastels while the black male courtiers attending her are clad in black, perhaps a visual anticipation of the surprising turn of the ending. Lighting designer Michael J. Whitfield has given the stage a dappled glow on an Indian summer. This is quite appropriate for a play that concludes with the competing voices of Spring versus Winter and one that suddenly leaves spring behind to face a winter of mourning.

Michael Langham, now 88, returns to Stratford, where from 1956 to 1967 he was its second Artistic Director, to direct there what is known to be his favourite play by Shakespeare for the third time. The first time was in 1961, the second in 1983, remounted the following year. Although the performances of most of the cast are merely adequate, his love for the play still shines through in the sense of gentleness and respect that seems to pervade attitude the entire cast. If only the Conservatory students could interpret their line with the pointedness of Donaldson, Winter-Culliford and Tree, perhaps we’d get more of a glimpse why so many Shakespeare scholars view this as the Bard’s first masterpiece.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: Jesse Aaron Dwyre, Trent Pardy, Ian Lake and Jon de Leon (standing); Michelle Monteith, Melanie Keller, Alana Hawley and Dalal Badr (seated). ©David Hou.

2008-06-11

Love’s Labours Lost