Reviews 2008

✭✭✭✭✩

Lope de Vega, directed by Laurence Boswell

Stratford Festival, Tom Patterson Theatre, Stratford

June 27-October 4, 2008

"¡Viva España!"

“Fuente Ovejuna” is the first play of Spanish Golden Age ever produced by the Stratford Festival. Spanish Golden Age drama developed simultaneously with Elizabethan and Jacobean drama and like its English counterparts is one of the greatest periods in world drama. For that reason alone, “Fuente Ovejuna” is worth seeing. What’s even better, a British specialist in the Spanish Golden Age, director Laurence Boswell, has given the play a new translation and his production has made it into one of the most exciting plays at Stratford this season.

Félix Lope de Vega Carpio (1562-1635), along with Tirso de Molina (1571-1648) Calderón (1600-81), is one of the three great masters of Spanish Golden Age drama. In his own time he was viewed as a prodigy of nature said to have written over 1,500 plays along with important works in prose and poetry. Of these 1,500, 500 ascribed to him have survived of which 300 so far, still an astounding amount, can definitely be attributed to him. “Fuente Ovejuna”, written and produced about 1611-13 and first published in 1619, is based on an historical incident. In 1476 the villagers of the town of Fuente Ovejuna (“the sheep’s spring”) rebelled against their feudal overlord Fernán Gomez de Guzmán and violently killed him to avenge the series of atrocities his had committed in the town. The villagers pledged their allegiance to King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, whereas Guzmán, a Commander of the elite knights of the Order of Calatrava, had aligned himself with King Alfonso of Portugal and Princess Juana of Castile, their competitors vying for control of the Iberian peninsula.

Lope de Vega is very different from Shakespeare in his portrayal of the general populace. A glance at the Jack Cade rebellion in “Henry VI, Part 2”, the mob in “Julius Caesar” or the population of Rome in “Coriolanus” reveals an elitist view of the people as giddy, changeable, easily swayed entity that can be led any way a strong leader chooses. In “Fuente Ovejuna” Lope takes the completely opposite approach by presenting the townsfolk as the incorruptible collective hero of the play. Rebellion against authority was a dangerous topic for any playwright but here Lope has the historical excuse that Guzmán has aligned himself against not just Fuente Ovejuna but against the eventual uniters of Spain to whom the townspeople pledge allegiance. Unlike Shakespeare, the story of kings and queens is placed firmly in the background while the lives of the common people take the foreground.

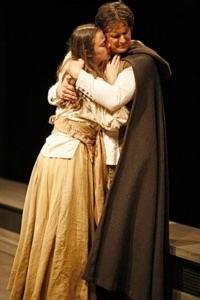

To provide an example of Guzmán’s villainy, Lope focusses on the love of the peasant Frondoso for Laurencia, the mayor’s daughter. She and her friend Pascuala have a low opinion of men from what they’ve seen in the village and especially from the Commander. Frondoso hopes through his steadfastness to win her love, but she is also being pursued by Guzmán. When Guzmán tries to force himself on Laurencia in the forest, Frondoso takes up the Commander’s crossbow and orders Guzmán away. By this action Frondoso finally wins Laurencia’s heart. In a dramatic scene Guzmán interrupts their wedding celebration to arrest Frondoso for future execution and to kidnap Laurencia. For the villagers this is the final straw. In remarkable parallel scenes first the men and then the women meet urged on by Laurencia who has escaped from Guzmán to take arms against the Commander and his guards, to storm his fortress and kill him to free Frondoso.

The production features a cast of 29, many in several roles, all well chosen and giving the kind of ensemble performance in a unified acting style one finds so rarely in plays at Stratford. Jonathan Goad is excellent as Frondoso showing the earnest young man’s frustration at Laurencia’s disdain and joy at her eventual approval. Laurencia is one of the juiciest roles Sara Topham has been assigned and it’s a pleasure to see how she rises to the occasion. The emotional arc from a proud peasant girl to the battered woman who has barely escaped Guzmán’s clutches is a great one and her harangue of the male villagers who sat by and did nothing is immensely forceful and impressive. If there is a flaw it is in the performance of Scott Wentworth, who can’t quite convey the depths of absolute evil that is Commander Guzmán. Guzmán does tell what he thinks are jokes but Wentworth tries to wring laughter from them when in fact further depressing evidence of the man’s misogyny and utter disdain for the lower classes. Stephen Kent as the Grand Master of the Order of Calatrava blusters when he should seem most sincere. David W, Kelley, as Guzmán’s henchman Captain Flores fails to find the right tone for his elaborately sartorial description of Guzmán in battle but is otherwise effective.

Many directors might be tempted to assign the comparatively minor roles of Ferdinand and Isabella to minor actors. Luckily, Boswell does not make that mistake and gives then to Geraint Wyn Davies and Seana McKenna. This is very important, for though their stage time may be small their impact is great. They represent the ideal of a Spain ruled by love and justice that they on a grand scale and the villagers on a smaller scale are fighting for. The great impact that Wyn Davies and McKenna make in they short appearances provides a touchstone for morality in the entire play.

There are other standouts throughout the cast. Mengo, acted with a suitable dry wit by Robert Persichini, is the most comic character in the play but even he is beaten for trying without success to save the peasant girl Jacinta, a fiery Lindsay Thomas, from rape by Guzmán and his men. The gripping finale hinges on whether he will hold out under torture. Lope thus even gives the “clown” role significant depth that Persichini captures perfectly. James Blendick gives Esteban the town mayor exactly the right level of gravitas. Nigel Shawn Williams as light-hearted Barrildo provides an excellent foil for Mengo and Frondoso while Severn Thompson as Pascuala well performs the same function for Laurencia.

Peter Hartwell’s design focusses entirely in costumes to give a sense of time and place. Though the villagers eventually trade in their rather pretty outfits at the start for broken-down outfits after their battle, their initial appearance is perhaps too spotless and tidy at the beginning to suggest a class of people who are poor and oppressed. On the mostly bare stage, Michael J. Whitfield wide array of lighting techniques establishes time of day and significantly influences changes of mood. Edward Henderson’s incidental music and the live playing of musicians Graham Hargrove and Kevin Ramessar area pleasure throughout.

In short, don’t miss this great play that presents such a different view of the common people from what one finds in Shakespeare’s historical plays. In 2004-05 the Royal Shakespeare Company staged a highly successful Spanish Golden Age season with plays by Cervantes, Lope de Vega and Sor Juana de la Cruz that proved just how varied and vibrant this incredible rich treasury of drama is. Let’s hope that the powerful impact of this “Fuente Ovejuna” encourages the Stratford Festival to continue exploring the fascinating world of Shakespeare’s Spanish contemporaries.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: Sara Topham and Jonathan Goad. ©David Hou.

2008-07-20

Fuente Ovejuna