Reviews 2011

✭✭✭✭✩

written and directed by Ted Dykstra

Soulpepper Theatre Company, Young Centre, Toronto

July 15-August 11, 2011

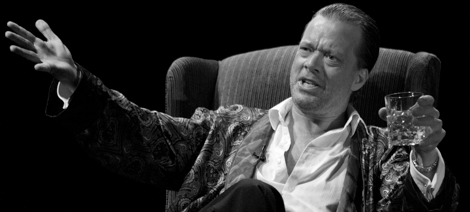

Ted Dykstra’s adaptation of The Kreutzer Sonata is a disturbing glimpse into a mind bursting with contradictions yet unaware of them. As Yuri, the narrator and protagonist of the story, Dykstra plays a man who thinks his extreme views are rational and believes that he is completely innocent of the terrible deed he has committed. Though there is no external action--Dykstra remains seated throughout the hour-long show--the tale is gripping as we try to reconcile Yuri’s narration of what happened with our revulsion at his thoughts and actions.

Leo Tolstoy’s novella The Kreutzer Sonata (1889) is a great work of fiction written for motives that can only strike us as bizarre. Tolstoy, who had been a frequenter of brothels in his youth and fathered at least fifteen children, thirteen by his wife, suddenly decided in 1888 that sexual intercourse should no longer exist. He wrote an epilogue to the novella in 1890 explaining explicitly that that was his intention in writing in. This was one stage in his spiritual awakening that began in the 1870s and culminated in his most important non-fiction work, The Kingdom of God is Within You (1894), the founding text of a movement called Christian anarchism.

In his adaptation Dykstra has the insight that what Tolstoy claims as his intention is not the only possible view of the text. Indeed, the reason why certain works of art intrigue us over the centuries is that they take on meanings far beyond what their creator may have imagined. By simply cutting the story back to its basic facts and presenting Yuri’s interpretation of them, Dykstra invites us to compare the two to determine whether Yuri’s views are really as rational as he thinks they are.

Yuri’s hatred of his wife begins when she receives a prescription for contraceptives because her doctor believes that bearing any more children would endanger her health if not her life. To Yuri, the only point of marriage is the production and raising of children, so he sees there is no longer any reason, except for social convention, for them to remain together. He also assumes that his wife Sonia feels that this prescription has freed her from responsibility to Yuri. When Yuri invites Nikolai, an old friend, to his house, he is unhappy to find how well he and his wife get along. A renowned pianist, Nikolai encourages Sonia to take up the violin again. Eventually, the two plan to play Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 9, known as the “Kreutzer” Sonata (1803), at a gathering at Yuri’s home. At this Yuri is overcome with jealousy. At the recital itself he can barely control his rage. Music itself he says should be outlawed because it draws a person against his will into the mind and emotions of the composer. Besides that, as with the sonata for violin and piano, it allows men and women to mingle and become close, when they should remain separate. And, specifically, as Yuri sees it, playing music with Nikolai produces a kind of ecstasy on Sonia’s face that he finds indecent. After the concert Yuri nearly kills Sonia but manages to control himself. When he return unexpectedly from a trip and finds the two dining together in his house, tragedy occurs.

Whether Sonia was or was not faithful we never know. What is clear, however, is that Yuri cannot stand anything that he cannot control. To lose oneself in music that many would describe as a positive experience Yuri experiences as an assault on his self-control. To see another lost in playing music that many would similarly describe as positive he sees as loss of will. Through his emphasis on the musical aspect of the story rather than on its sexual implications, Dykstra turns Tolstoy’s novella into a meditation on the power of art with the story drawing us in just as the sonata drew Yuri in--albeit with profoundly different effects. Yuri is so articulate in explaining precisely why he hates music, he unintentionally uncovers what gives it its force.

Dykstra’s narration is skillfully blended with excerpts from the “Kreutzer” Sonata, that give the story its name, played at significant moments. Dykstra’s only props are a water jug, a glass, handkerchiefs and a Bible, which Dykstra uses in a masterful manner to indicate Yuri’s increasing stress as he tells his tale. Especially, noteworthy is Lorenzo Savoini’s lighting that shifts so subtly to underline Yuri’s moods that its effect is almost subliminal.

It would be very easy to regard Tolstoy’s Yuri as a portrait of a soul in torment. What emerges from Dykstra’s adaptation is even more distressing. The calm façade Yuri endeavours to present hides a soul that does not even recognize that its torment arises from its own inhuman rigour.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: Ted Dykstra. ©2011 Cylla von Tiedemann.

For Tickets, visit www.soulpepper.ca.

2011-07-17

The Kreutzer Sonata