Reviews 2012

✭✭✩✩✩

written and directed by Jordan Tannahill

Suburban Beast, Berkeley Street Theatre Rehearsal Hall, Toronto

September 7-22, 2012

“Feral: ‘... lapsed into a wild from a domesticated condition’” OED

Jordan Tannahill’s latest play Feral Child has an intriguing premise and a promising beginning, but the way Tannahill manages his plot is ultimately disappointing. Even more disappointing is the enormous disparity in ability between the actors who take on the play’s two roles. While the one gives a beautifully nuanced and emotionally rich performance, the other doesn’t yet have the basic skill set to be on stage.

The acting space is a defined by a white carpet around which an audience of about 40 can be seated on three sides. Designer Joe Pagnan’s simple set immediately places us in the typically messy bedroom of a teenaged boy. In the well-conceived silent prelude to the action, a cleaner (Cynthia Ashperger), whom we find is named Adrijana, comes in to do finish her work. She has to use smell to sort the dirty clothing from the clean that lie strewn about the room and looks with frustration on the bits of cereal and chips lying near their open packages on the floor. All would be ordinary except that Adrijana opens the inhabitant’s laptop and seems to be looking a photos. She clutches the inhabitant’s jacket, drinking in its scent as tears start to form and fall.

After this unusual moment she exits to fetch materials to get rid of a stubborn stain that some of the clothes had hidden. Then the room’s inhabitant Jeremy (William Christopher Ellis) enters, an unremarkable teenager, earbuds in place, who decides the coast is clear for him to jerk off to some porn on his laptop. He notices the laptop has just been used but doesn’t seem to care and even leaves the door to his room open. It’s no surprise then that Adrijana discovers him in mid-wank.

As we move from silence to speech, we discover that Jeremy has decided not to go to school today and that this is the first time he and Adrijana have met. He plies her with a battery of initially innocuous but increasing rude questions that she answers as she tries to finish her work so she can leave for the day. Jeremy accuses Adrijana of cleaning his room in much more detail that his parents’ room, of leaving books about for him to find and read and finally of invading his privacy by looking at pictures of him on his laptop.

It transpires that many things about Jeremy – his isolation from his peers, his gestures – remind her of the son she left back in Bosnia. When Adrijana rather bizarrely changes out of her work clothes into her street clothes in front of Jeremy apparently to go home, the nature of her interaction with Jeremy changes and she begins addressing him as Bojan, the name of her son. Throughout this section it is unclear whether Jeremy is merely playing along with Adrijana’s fantasy or is, in fact, Bojan pretending not to recognize Adrijana as his mother. His constant prompts for her to continue telling the story of the past suggest the former. Her own conclusion of what has happened suggests the latter. She tells the horrific tale of how the private school she sent Bojan to was really a military training academy that turns teenagers into vicious fighters and of how her Muslim husband was brutally murdered.

While it is happening, this section is fascinating since we begin to think that this exchange is really some form of habitual game-playing between master and servant and that this is clearly not the first time Adrijana and Jeremy have met. The great disappointment [spoiler alert] is that a sudden lighting change reveals that this entire section merely was fantasy, a way of giving us access into the unspoken thoughts playing in Adrijana’s head when she says that Jeremy reminds her of her son. What had been dramaturgically exciting is revealed as merely a ploy for Tannahill to uncover the Adrijana’s back story.

Tannahill’s point is that the many menial labourers we encounter in boring places like Oshawa where the play is set have abilities far beyond the jobs they do and qualifications, like Adriana’s Ph.D., that are not recognized in this country. We see recent immigrants silently go about their work with little idea of the agonies they have suffered that have brought them to Canada. This is a worthy goal but it does mean that Adrijana’s story is just a means to an end and leaves the two characters simply as cleaner and client’s son as they were at the start. He has really learned nothing important about her and she (and we) have learned virtually nothing about him except that he’s an annoying brat. Is Bojan the only “feral child” or are we supposed to see some lapse into wildness in Jeremy? If so, mere rudeness is not a strong enough sign.

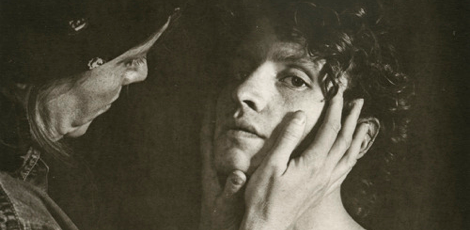

Ashperger gives a wonderfully warm portrait of a woman who has mostly succeeded in accepting her new position in life as best she can. Yet, she is expert at revealing the oceans of pain that the seeming ordinariness of her remarks conceals. Ellis, on the other hand, is not yet ready to be a stage actor. He has appeared in film and television, but those abilities do not directly translate to the stage. He does not know how to project, often using the sub-conversational level popular in movies, and speaks in the same irritatingly uninflected voice no matter what he is saying. While Ashperger can bring detail and nuance to her simplest lines, Ellis’s monotone can’t even give his basic lines meaning. He doesn’t act with his whole body as does Ashperger, but only from the neck up as if he were in constant close-up.

As a director, Tannahill paces the 75-minute show well and shows real talent for creating interest in the silent section that begins the play. He does get himself into trouble by requiring Ellis to bring on an especially gruesome prop that he then has no means of removing from the scene when its function has ended. I would suggest he eliminate the prop entirely and replace it with a projection on the vast blank wall of Jeremy’s bedroom that seems to cry out for greater use throughout the action.

Tannahill is only 24 and shows great promise as both a playwright and director. His comparing Feral Child to Sarah Kane’s Blasted is a bit of hubris since Kane’s play is set in the midst of the horror of war while Feral Child is about horror remembered in a safe place, and even then is only interested in those memories for a generic purpose rather than fully immersing us in a situation that tests our faith in humanity. Tannahill has many projects coming up and I will be interested to see how he develops. I would also go out of my way to see any play that Ashperger appears in. Ryerson University is lucky to have her as Director of Acting in its Drama Department.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: Cynthia Ashperger and William Christopher Ellis. ©2012 Mark Peckmezian.

For tickets, visit www.canadianstage.com.

2012-09-09

Feral Child