Reviews 2013

✭✩✩✩✩

by Sarah Berthiaume, translated by Nadine Desrochers, directed by Ted Witzel

Canadian Stage, Berkeley Street Theatre Downstairs, Toronto

October 17-27, 2013

Kate: “I think I’d like to be trampled by a herd of bison”

Sarah Berthiaume’s Yukonstyle premiered to much acclaim at the Theater d’Aujourd’hui in Montreal in April earlier this year. That the Montreal critics saw anything to praise in this dismal text makes one believe there really are two solitudes in Canada. Perhaps translator Nadine Desrochers could only make the “poésie” that critics lauded in Berthiaume’s frequent narrative passages sound like pretentious purple prose in English. But the translator is not to blame for such basic flaws as lack of plot, lack of purpose and lack of engaging characters. Just last month Canadian Stage presented Berthiaume’s first play The Flood Thereafter (2008) that suffers from the same flaws. Yukonstyle, which has even less substance that Flood, suggests that as a playwright Berthiaume has not developed at all in five years.

Yukonstyle is based on an incident in Berthiaume’s life where she lived in the Yukon for a month to try to forget an unhappy relationship. Despite that, it follows the same basic pattern as The Flood Thereafter – stranger arrives in town filled with grief, stranger’s visit is prolonged, stranger departs and everything is fine. In Flood the visitor is a man who unwillingly stays in a small Quebec fishing village. In Yukonstyle the visitor is a hitchhiker who willingly stays in a small town in the Yukon. In both plays the visitor does not serve as a catalyst for the subsequent events as one might imagine. Events takes their own course so that we wonder what the point of the visitor is at all.

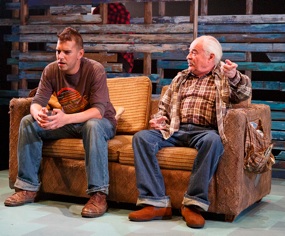

In Berthiaume’s story Kate (Kate Corbett), a pregnant, 17-year-old with a broken arm and dressed like a hooker, is picked up by Yuko (Grace Lynn Kung), the chef at the local diner. For unknown reasons Yuko invites Kate to stay in her house as long as she wants. This angers Garin (Ryan Cunningham), Yuko’s housemate and dishwasher who understandably doesn’t like the change in the situation. The situation also makes no sense because all Kate wants is an abortion clinic and the nearest one to where Yuko lives is in Vancouver. Meanwhile the 2007 trial of serial killer Robert Pickton is playing out on television. Garin is especially interested because he has the suspicion that his mother Goldie (also Kung), a native woman who disappeared twenty years ago, may have been one of Pickton’s victims. Garin presses his Francophone father Pops (François Klanfer) for information about his mother until he finally tells the whole story. After two months Kate finally leaves, according to Berthiaume’s forced symbolism, the darkness of the Yukon for the “sunshine of Vancouver” [sic].

Contrary to its title, Yukonstyle has virtually nothing to do with the Yukon since its attention is constantly focussed elsewhere. The principal focus is Vancouver where the trial is held and where Kate wants to go. The secondary focus is Japan, where Yuko is from, having left after her sister died.

Just as the plot has nothing to do with the Yukon, neither does the language. As in Flood, Yukonstyle alternates between would-be poetic narration and profanity-laden but inconsequential dialogue. Sometimes characters narrate their own actions, sometimes those of others. As in Flood, events of the past are narrated with actors taking on other roles, but actions in the present are also narrated seemingly at the whim of the author. At least Flood with its reference to the Sirens in the Odyssey has some sense of specificity. In Yukonstyle, the “poetic” passages are so general with their references to emptiness, snow, trees, wind, sky, cold, that the action could be taking place in any small town in the northern part of any of the provinces from BC to Newfoundland and Labrador.

Given how little effort Berthiaume has put into creating plot, characters or setting, it’s not surprising that director Ted Witzel and the cast fail to make anything of the play. Witzel’s main insight is to have lighting designer Bonnie Beecher fade the projected “snow” from the television set back and forth into the projected snow falling outside. I guess what’s outside and what’s on television, even if it’s static, is chilling.

Kate Corbett’s Kate is truly annoying, rather like Betty Boop dressed as Madonna circa 1984. Luckily, Corbett drops the squeaky voice when she does her narration. Ryan Cunningham is good at being generically intense but what’s with all the bizarre arm gestures during his big monologue of Act 2? François Klanfer tries, albeit in vain, to give more substance to his role as “dying old drunk”. Grace Lynn Kung at least attempts to give Yuko a surface layer and a deeper layer and her turns as the sensuous Goldie and the implacable Raven give her the chance to show her versatility. (By the way, “Harajuku” in Tokyo is pronounced “Haráj’ku”, not “Hárajúku” as Kung pronounces it.)

Through Goldie’s narrative of growing up in a residential school, Berthiaume tries to force a comparison between Pickton’s choice of native women as his victims and Canada’s victimization of native people. Yet, at the same time, you can’t but feel that Berthiaume is exploiting the trial itself to lend her otherwise bland creation the kick of transgression.

The Canadian Stage website calls Yukonstyle, “An arrestingly honest and poignant exploration of what it means to be a young Canadian living in the north”. That is pretty much the opposite of what it is. “An unremarkably artificial and tedious miscellany of scenes about young and old living north of Vancouver” is closer to the truth. “Ninety minutes wasted” is even closer.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: (from top) Grace Lynn Kung and Kate Corbett; Ryan Cunningham and François Klanfer. ©2013 Bruce Zinger.

For tickets, visit www.canadianstage.com.

2013-10-18

Yukonstyle