Reviews 2013

✭✭✩✩✩

music and lyrics by Pete Townsend, book by Pete Townsend & Des McAnuff, directed by Des McAnuff

Stratford Festival, Avon Theatre, Stratford

May 30-October 19, 2013

“He stands like a statue, Becomes part of the machine”

The rock opera Tommy is like a Christmas box wrapped in heavy, gaudy paper, tied with shiny ribbons and dusted with glitter. The wrapping is so elaborate you hate to open it – and your hesitation is justified because inside there is nothing but scraps of tissue paper. If all you want from a musical is spectacle, that’s exactly and exclusively what Tommy supplies. If what you want is emotion, complex characters and a story that makes sense, you had better look elsewhere.

Tommy first had life as a concept album by the British rock group The Who in 1969. It was the first work to be labelled a “rock opera” though, in fact, it was really a song cycle based on a loose and fairly ambiguous narrative about a deaf, dumb and blind boy called Tommy. The first fully staged version was performed in 1971. The first time the music was presented with a coherent narrative was in Ken Russell’s star-studded 1975 film overseen by Pete Townsend, the writer of the work’s music and lyrics. In 1992 Des McAnuff created a stage version of the musical with a book written by him and Townsend, that opened a year later on Broadway and won McAnuff a Tony Award for Best Direction of a Musical and Townsend a Tony for Best Original Score, though the musical lost out to Kiss of the Spider Woman for Best Musical.

The plot for the stage version covers a period from 1940 to 1966 and begins before Tommy’s birth, proceeds through Tommy’s rise to fame and ends with his renunciation of it. All this occurs in 21 scenes in only 103 minutes with an intermission between Scenes 12 and 13. The principal flaw in the musical, already discernible from these facts, is that the work has to cover too much plot in too short a time. The musical has so much narrative to get through to make sense of the songs on the album that there is virtually no time for characters, except for Tommy (and only in Act 2), to reflect on the actions they undertake. On the 1969 double album the precise time, place and staging of events is irrelevant in relation to the flow of the musical numbers. On stage, however, these assume prime important which results in the cast artfully scurrying about to change one scene to the next with only an average of less than five minutes playing time per scene. And this doesn’t take into account director McAnuff’s propensity for changing locations more than once even within the 21 scenes. The overall impression is of a large well-oiled machine in which the cast function less like people than cogs in the shape of automatons.

The mechanical lifelessness of the show is not helped by a story in which key points are either unexplained or contradictory. Captain Walker (Jeremy Kushnier) leaves his wife (Kira Guloien) to fight in the RAF in World War II. He is shot down over Germany and the RAF tells Mrs. Walker that her husband has died. The next year, 1941, she gives birth to Tommy and by 1945 she has taken a lover (Sean Alexander Hauk). As it happens, Captain Walker did not die, but was a POW. He returns to surprise his wife in England only to discover her with her lover. After a struggle he shoots the lover dead. Realizing that Tommy has witnessed everything the Captain and his wife, suddenly reconciled, tell Tommy that he did not see or hear anything and will not say anything about what happened. When in the next scene, the Captain is found not guilty for murder, the Captain and his wife notice for the first time that Tommy has become deaf, dumb and blind. Visits to medical experts provide no cure. Events have cascaded at such a pace that there is no time for Townsend or McAnuff to explore such obvious questions as what the Captain thinks about his wife taking a lover, what Mrs. Walker thinks about her husband’s sudden return from the dead and murder of her lover or what the Captain and his son think about seeing each other for the first time.

By Scene 7, the Walkers, somehow carefree (and rather stupid) after so much trauma, decide to have Tommy’s alcoholic Uncle Ernie (Steve Ross) babysit the boy. Ernie proceeds to sexually molest Tommy and even sings a song, “Fiddle About”, as he does so. The creators do not give us Tommy’s view of the assault. Next the Walkers leave Tommy alone with his sadistic Cousin Kevin (Paul Nolan), a self-confessed bully, who dumps Tommy in a trash can and later takes him to his friends to be humiliated. It is at Kevin’s friends’ hangout that Tommy discovers his gift for playing pinball. Meanwhile, Captain Walker is still desperate for a cure for Tommy and takes him to see a gypsy called the Acid Queen (Jewelle Blackman) who says she can cure Tommy with sex and drugs. Why the Captain doesn’t perceive the dodgy nature of the Acid Queen upon seeing her and her surroundings is unknown except that the creators would have to drop the song from their playlist.

Tommy is eventually acclaimed a “pinball wizard” but this news, known to everyone else, seems not to have reached the Walkers because they are still obsessed with curing Tommy. With more visits to doctors, the narrative becomes repetitive, the only new information being that Tommy is suffering from what we would now call conversion disorder, i.e. some traumatic incident has caused Tommy’s body to covert mental anxiety into physical deficits. At home Tommy’s mother, enraged that he does nothing but gaze at his own reflection in the mirror, breaks the mirror and, magically frees Tommy from his catatonia. This is a great image except that the creators have somehow forgotten that Tommy is blind and therefore could hardly see a mirror much less see himself in it.

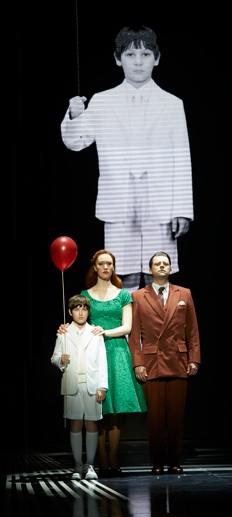

While the story seems to be nothing but a concatenation of pop clichés adding up to a pile of pretentious nonsense, the production itself is visually dazzling. Designer Sean Nieuwenhuis creates amazing effects by using simultaneous front projection onto a scrim and back projection onto a screen at the back wall that sometimes is changed for an LED wall for computer-generated imagery. Sometimes the imagery is corny as when doctors examine Tommy and the LED wall shows us doors which open revealing an ear, eye or mouth. “Aha, these are obviously Aldous Huxley’s ‘Doors of Perception’”, we think. Sometimes it is pedestrian as when the wall shows us beer glasses emptying as Uncle Ernie drinks down is beer. The worst aspect, however, is that video projection is used so extensively and is so dominant that the show seems more like an extended music video performed live than a live musical with a video background. Mcanuff has tightly choreographed the entire production, with the movement of actors and remote-controlled set pieces perfectly integrated with the music and the on-screen videos. The only relief from this dehumanizing precision comes from the dance choreography of Wayne Cilento, the choreographer in 1992, that gives some sense of life and spontaneity to this enormous clockwork machine of a production.

The entire cast give excellent performances given how little scope for individual expression the show gives them. One problem is that sound designer Andrew Keister has imbedded the vocals so deeply into the instrumentals that at least half the lyrics are obscured.

People going to Tommy and expecting another Jesus Christ Superstar will be keenly disappointed. Tommy may have a rousing score but it lacks any of the interpersonal or internal conflicts that draw a person into Superstar. In Superstar McAnuff managed to have high tech production enhance the storytelling. In Tommy he has allowed his love of the latest technology to overwhelm the storytelling completely. He is so obsessed with trying to startle the eye and ear he forgets to intrigue the mind or touch the heart.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: (top) Robert Markus as Tommy; (middle) Conor Bergauer, Kira Guloien and Jeremy Kushnier. ©2013 Michael Cooper.

2013-06-07

Tommy