Reviews 2013

✭✭✭✩✩

written and directed by Michael Shamata

Soulpepper Theatre Company, Young Centre, Toronto

July 16-August 17, 2013

“Modest Results”

Michael Shamata’s 1990 adaptation of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol has been one of Soulpepper’s staples since the company first staged it in 2001. Now Soulpepper presents Shamata’s significantly less successful 1996 adaptation of Dickens’ novel Great Expectations (1861). The reason for the difference is simple. A Christmas Carol, a short story that with its ghosts and presentation of tableaux, is already highly theatrical. Great Expectations is a three-volume novel about the spiritual education of the main character through reflection on how his view of the events of his life has changed over time. The sheer length of the material presents the first difficulty in adapting the work to the stage. David Edgar’s popular adaptation in 1980 of Dickens’ Nicholas Nickleby (1839) for the Royal Shakespeare Company was originally eight hours long, which he cut down to six hours for the show’s remount in 2006. Dickens’ novels are so full of incident at least that amount of time is needed to do them justice. The second difficulty in adapting Great Expectations is that it, unlike Nicholas Nickleby, is more about reflection than action.

Shamata’s adaptation falls into the trap of most adaptations of novels that in trying so hard to be faithful to the complicated plot it forgets to give us any particular perspective on the action. The adaptation has the effect of fast-forwarding through the novel to dramatize key scenes without giving us enough information to know why these scenes are important. This may be fine for people who already know the novel, but those who do not may find the action, with all its twists and turns, difficult to follow.

To stage the play Shamata has changed the seating in the Michael Baillie Theatre into an alley configuration with the divided audience facing each other across the bare stage. This method obviates the need for scenery and facilitates rapid changes of location, but why designer Shawn Kerwin’s faux-brick column is needed, when so much else is imagined, is a mystery. It would have been more inventive to have represented everything in the play with only the eight chairs on stage.

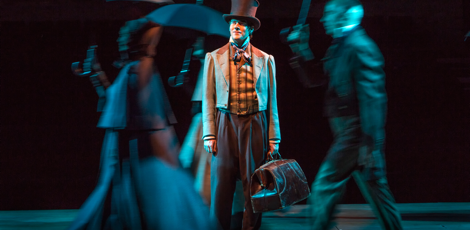

The central role of Pip could be a real tour de force in acting for Jeff Lillico, but sadly this is one challenge that he cannot quite meet. Shamata begins the play with Pip as an old man looking back on his life. His first scene is when he is aged seven and meets the escaped convict Magwich (Oliver Becker) in a graveyard. Pip’s kindness to the frightening man has repercussions that Pip will not realize until much later in the story. Lillico starts off on the wrong foot by failing to make a significant transition between the old Pip and the young Pip. Indeed, as the play progresses Lillico’s 7-year-old Pip is not much different from his 14-year-old Pip or his 21-year-old Pip. When Lillico delivers his narration he often begins in a Canadian accent that awkwardly becomes the upper-class British accent of the older Pip. Pip at ages seven and fourteen ought to have the lower-class accent of his foster father Joe Gargery (Oliver Dennis), but Lillico remembers this only intermittently. Otherwise, Lillico always suggests that Pip is brimming with emotion that he cannot always express. It is the fault of the script and direction that it is not always clear why Pip’s feelings change. Shamata simply does not show how Pip moves from revulsion at Magwich’s revelation in Act 2 to a willingness to help him.

Trying to cram three volumes of plot into only two hours and forty minutes means that we rarely get to see characters long enough to care about them. Shamata’s adaptation doesn’t even create a bond between us and Pip. The few characters we do care about are the ones Shamata allows enough time to express their own views of life. The character who makes the greatest impression is Joe Gargery, whose satisfaction with his low estate in life stands as the prime contrast to Pip’s unquenchable desire to become a gentleman. Oliver Dennis brings his customary warmth and self-deprecating humour to the role that immediately engages the audience. Dennis does so again in the lesser role of Wemmick, a lawyer’s clerk, who makes a strong distinction between what he does and says in the office and at home. It is largely because of Dennis’s gifts as an actor that he can so fully delineate a character so quickly with a few deft strokes.

Paolo Santalucia makes a jolly Herbert Pocket, the clerk Pip rooms with in London, and Oliver Becker a forceful Magwich, at least when you can understand what he’s saying. Otherwise, the actors have little chance to give their characters more than two dimensions. Estella, the girl Miss Havisham has trained to break men’s hearts and who captures Pip’s, ought to be a fascinating figure, but Shamata has decided to have two actors play the role. It’s wonderful to see so assured a child actor as Naomi Agard play the Young Estella, but it is odd to see Lillico play a child with an actor who really is a child. Besides, if Lillico has to play Pip from age seven into his 30s, why shouldn’t Leah Doz, who plays the older Estella do the same so we can see the changes in both? Doz ably distinguishes her two roles as the kind girl Biddy from Pip’s hometown and the haughty Estella, but she should project to at least the same volume as the other actors.

C. David Johnson presents the lawyer Jaggers only as coldly indifferent when he could at least suggest Jaggers knows more than he is willing to tell. Deborah Drakeford presents Pip’s sister Mrs. Joe only as a shrew and oddly makes a greater impact as Jagger’s mysteriously silent housekeeper Molly. What John Jarvis is trying to do with Mrs. Joe’s Uncle Pumblechook is anybody’s guess, but he makes a more positive impression as Wemmick’s comical “Aged Parent”. Jesse Aaron Dwyer cuts such a forceful figure as the disdainful Drummle, Pip’s rival for Estella, that we expect to see more of him, but do not.

Overall, what the production lacks is theatricality. Shamata makes Pip’s entry into London impressive with his being jostled about by busy Londoners carrying umbrellas, but other key moments fail. The death of Miss Havisham and the burning down of Satis House is a central symbol in the novel of the destruction of vanity and revenge and the wiping away of Pip’s illusions about his life. Yet, the scene passes in less than a minute with a paltry amount of red light and smoke and a red ribbon to signal the disaster. Shamata stages the climactic boat chase on the Thames without a hint of its location. Even worse, despite being overly faithful to the plot, he strangely does not have Magwich kill the villain Compeyson (Jarvis again), an act that ties up several plot strands.

It’s hard to know what audience the play is intended for. Those who know the novel will find it more interested in the complexities of the plot than in the complexities of the characters. Those who don’t know the novel will wish it presented more analysis of the action. The one theme Shamata emphasizes is Joe’s statement that “life is made of ever so many partings welded together”, but that is more a description of the action than an analysis of it. What’s missing is an emphasis on the notion that so many of the unhappy characters in the novel have built their lives on illusions, whether their own or those supplied by others. The title Great Expectations should acquire an increasing sense of irony. The past has taught us to expect great things of Soulpepper, but here it is best to keep one’s expectations modest.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: (top) Jeff Lillico as Pip (foreground) with Deborah Drakeford, Leah Doz and Oliver Dennis; (middle) Kate Trotter as Miss Havisham. ©2013 Cylla von Tiedemann.

For tickets, visit www.soulpepper.ca.

2013-07-17

Great Expectations