Reviews 2014

✭✭✭✩✩

by George Frideric Handel, directed by Marshall Pynkoski

Opera Atelier, Elgin Theatre, Toronto

October 23-November 1, 2014

Alcina: “Vi cerco, e vi ascondete? / vi comando, e tacete?”

With Alcina, Opera Atelier, Canada’s baroque opera company, finally produced its first full-length opera by Handel. Because Opera Atelier has primarily focused on operas of the French baroque where dance is such an integral part, Alcina was a logical choice since it is one of Handel’s few operas with extensive ballet music. With Alcina director Marshall Pynkoski took the company a few steps away from its mandate of staging historically informed productions. Musically the performances were on a very high level. Visually, the results were mixed.

The story of Alcina (1735) is based on an episode from Ludovico Ariosto’s epic poem Orlando Furioso (1532), which also provided the plots for other operas by Handel and his contemporaries. In this fantasy about Charlemagne’s wars against Islam, the knight Ruggiero has landed on a magic island ruled by the sorceress Alcina and her sister Morgana. Alcina uses her magic to force Ruggiero to believe he loves her. Meanwhile, Ruggiero’s fiancée Bradamante, disguised as her brother Ricciardo, has landed on the island with Ruggiero’s tutor Melisso, who has come armed with a magic ring that allows the wearer to see through illusion. As we discover from Alcina’s general Oronte, who is hopelessly in love with Morgana, Alcina’s island is entirely an illusion built from the souls of her former lovers. While Melisso and Bradamante try to win Ruggiero away from Alcina in the main plot, in the comic subplot Morgana falls in love with Bradamante, not realizing that “Ricciardo” is a woman.

Pynkoski’s central preoccupation in Alcina is twofold: first, the notion that Alcina’s magic island is an illusion, and second, that the illusion is composed of the souls of rejected lovers. To emphasize the first notion, Pynkoski, like many directors before him, most notably the great Herbert Wernicke in 1996, has decided to identify Alcina’s island with the world of the theatre itself. Therefore, during the overture the painted front drop rises, to reveal a stage bare to the very back wall with dancers stretching and stage managers conferring while only one dancer, choreographer Jeannette Lajeunesse Zingg dances. Soon Alcina (Meghan Lindsay) enters in character and gestures at the empty space, whereupon a painted backdrop and legs descend creating the familiar stage décor for an 18th-century opera. By the end when Alcina loses her power and the island disappears, the backdrop and legs again expose the bare stage.

Other ill-conceived images of film director Ben Shirinian included the gradual appearance and disappearance of Alcina’s eyes, then mouth, then face, which looked all too much as if modelled on makeup advertising. His idea for the ending was puzzling. In the story, Ruggiero and company board Melisso’s waiting boat and sail away from the island. Shirinian, however, shows us a odd white blob on the horizon that, approaching, looks like it might be the three top sails of a ship, although missing any ship below them. If the image is meant to be a ship, it ought to be sailing away from the island rather than towards it.

In general, Pynkoski seemed to be trying far too hard to overcome the perception of some that an opera seria like Alcina is too static. The complex plot alone should be a sign that the difficulty is not stasis but too many twists and turns. Nevertheless, in overcompensating for this perceived stasis, Pynkoski plays up physical action in the first half of the opera to the point of slapstick. There are only so many times that actors striking, pushing or pulling each other or falling to the ground can be funny. Similarly, Pynkoski overused the image of singers rushing across the stage to hug the proscenium as a sign of emotion.

Pynkoski deals with Handel’s da capo arias in a peculiar fashion. In the first half of the opera, he has the singers come downstage centre to sing the da capo portion directly to the audience with ornamentation to show off the singer’s technique, which was, of course, the original point of such arias. This idea well suited the conscious artificiality of the stage-as-world metaphor that begins the production. Then, in the second half of the opera, the singers perform the da capo sections in character and wherever they happen to be on stage. It seems as if Pynkoski learned in the course of directing that the da capo sections can be used as more than showpieces but can also become useful moments when characters reflect on thoughts they have just expressed.

To place so much emphasis on the sheer number of Alcina’s previous lovers undercuts the important point that Ruggiero is the first person Alcina has truly loved. It is Alcina’s experience of this truth, rather than illusion, that causes her to lose her powers and call on the gods in vain “Vi cerco, e vi ascondete? / vi comando, e tacete?” (“I look for you and you flee? I command you and you are silent?”) (Act 2, Scene 13). This is long before Ruggiero and Milisso destroy her magic kingdom in Act III. Pynkoski’s emphasis makes it difficult for Meghan Lindsay to generate much sympathy for Alcina in the second half of the opera. Lindsay uses her hard, slightly chilly soprano to great effect in the first half to create an imperious, diabolically charming figure. Yet, when Alcina reacts to Ruggiero’s betrayal in “Ah! Mio cor! Schemito sei!” and in her subsequent laments, Lindsay can not win us over to Alcina’s side despite her exquisite singing and expressivity.

Allyson McHardy is superb in the trousers role of Ruggiero. In acting she convincingly adopts the walk and gestures of a male. In singing, her warm amber-coloured contralto only grows in power and richness until a fantastically vital, swaggering account of “Sta nell'ircana pietrosa tana” filled with thrilling runs seals her triumph in the role. It deservedly won the longest ovation of the evening.

Mireille Asselin is an absolute delight as Morgana, her bright, diamantine soprano ideal as the spritely foil to darkness, both vocal and psychological, of Lindsay’s Alcina. Of the soloists Asselin showed the greatest variety in ornamentation in the da capo sections of her arias, with the Queen of the Night-like staccato embellishments of “Tornami a vagheggiar” a particular highlight.

Wallis Giunta gives a vivid account of Bradamante, playing up the comedy of trying to thwart Morgana’s advances while capturing the ardour of the woman’s joy seeing Ruggierio finally released from Alcina’s enchantments. Giunta’s mezzo-soprano lies comfortably between the brightness of Asselin’s voice and the darkness of Lindsay’s. Unaccountably it acquires a matteness in the rapid runs of “Vorrei vendicarmi”, only to emerge in richness and beauty in a more lyrical aria like “All’alma fedel”.

To have tenor Krešimir Špicer, who has sung the title roles in La Clemenza di Tito and Der Freischütz for OA, sing the role Oronte was luxury casting. His voice with its splendid combination of heft and nimbleness was equally effective in bringing out the comedy of spurned love in “È un folle, è un vil affetto” as well the depth of requited love in “Un momento di contento.”

To bring the opera in under three hours, Pynkoski cut the subplot involving Oberto. Nevertheless, it was a pleasure to see Alcina with all of the ballet music Handel wrote for Marie Sallé. Lajeunnesse Zingg led the corps de ballet as Sallé would have done, creating graceful patterns of period-style footwork. For the entrapped soles of Alcina’s lovers, Lajeunnesse Zingg employed the more-floor-oriented style of modern dance.

Under David Fallis, the Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra emphasized the wide range of dancelike rhythms that animate the entire score. Opera Atelier’s first foray into the use of film left one with the question of how theatre of the period would have produced the same effects. It’s more than ironic for an Opera Atelier production to pose such a question since until now OA has so imaginatively provided the answer.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: A version of this review will appear later this year in Opera News.

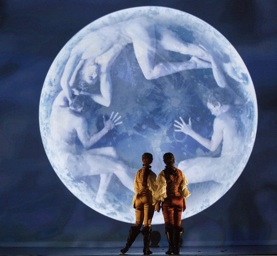

Photos: (from top) Corps de ballet with image of Meghan Lindsay as Alcina; Wallis Giunta and Allyson McHardy look at the moon; Allyson McHardy, Mireille Asselin and Wallis Giunta. ©2014 Bruce Zinger.

For tickets, visit www.operaatelier.com.

2014-10-26

Alcina