Reviews 2014

✭✭✭✭✩

by Beatriz Pizano, Trevor Schwellnus & Lyon Smith, directed by Trevor Schwellnus

Aluna Theatre, Aluna Studio, Toronto

October 30-November 30, 2014;

The Theatre Centre, 1115 Queen St. West, Toronto

January 21-24, 2016

“The challenge of maintaining our humanity in trying times”

Aluna Theatre’s new show, like all good political theatre, has the explicit goal of raising awareness of our situation in the world. Co-created and performed by Beatriz Pizano and Trevor Schwellnus, the same team behind the brilliant Nohayquiensepa of 2011, along with Lyon Smith, What I learned from a decade of fear examines what has changed in our thinking and behaviour since the “War on Terror” began in 2001. What Pizano, Schwellnus and Smith find is shocking in two different ways. First, the play forces us to acknowledge that the war on terror has gone on for so long that we have begun to take it and all its human and financial costs for granted. Second, the play makes us see that rather than making us in North America feel safer, it has in fact completely eroded the trust that used to bind people together.

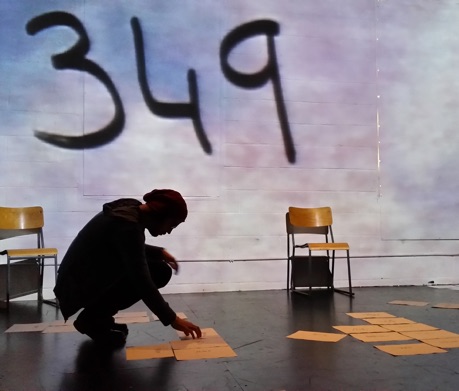

The play begins in the tiny Aluna Studio*, a room that seats only 30 audience members, with Beatriz Pizano and Lyon Smith alternately writing figures on sheets of paper that are projected onto the back wall of the acting space. Each writes the number, explains what it means, says “thank you” and places the sheet of paper in a pattern among other sheets already on the floor of the acting space. The numbers are all statistics, and they are horrifying. $12 billion = monthly cost of war in Iraq. 350,000 = number of people killed since 2001 due to direct war violence. 3990 = number of American troops killed in Iraq. 82,000 = number of Iraqi civilians killed since war began. 360,000 = US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan with traumatic brain injuries. 1892 = number of suicides of US veterans of war on terror. The list continues and is up to date. It includes: 1 = the number of Canadians killed in Canada by terrorists since 2001, a reference to Corporal Nathan Cirillo.

While Trevor Schwellnus serves as stage manager as well as lighting and sound technician and remote camera operator, Beatriz Pizano and Lyon Smith negotiate the stage. We note that although more than half the playing surface is covered with pages of statistics, neither of them steps on one of these pages. In fact, the point is that they both literally step around the facts they have presented. Their careful movement becomes a physical metaphor for how we mentally have come to ignore statistics that we once paid so much attention to when the war on terror began in 2001.

The second phase of the performance involves Pizano playing herself playing an interrogator and Lyon Smith playing an ordinary guy by playing himself. As Schwellnus states in his director’s note, “All our public language now is oppositional, and leads us to look for enemies”. Pizano’s first line of inquiry concerns whether Smith is happy. Her questions pull apart Smith’s ability to perceive happiness in others as well as in himself, thus casting doubt on his abilities of perception. Parallel to the actors’ movements around the facts, her questions also probe whether he can be happy if he knows other people are suffering. The truth, of course, is that he can be. Pizano interpretation is that is he must be callous.

After an excerpt from an old training film about the use of repeated questions in interrogation to trip up the interrogatee, Pizano begins again, this time with a focus on what Smith had for breakfast. Comic and trivial though this may seem, by the end of this section Smith has had to admit that he buys organic bananas because he trusts that the label is true even though he does not know if it is true. His buying of foods marked “organic” is thus a form of belief.

Then there is a disturbing video in which soldiers in a helicopter or perhaps manning a drone get Middle Eastern men carrying weapons in their sights and whoop as they shoot them down as if playing a video game. After this Pizano takes her questioning farther to find out under what circumstances Smith would kill another person. Smith has to admit, as most people would, that if someone were going to harm his children and he had no other recourse to stop them, he would likely resort to violence. By carefully manipulating her questions and playing on half-truths, Pizano succeeds in asserting that Smith, though just an ordinary guy, actually has it in him to kill a major political or religious figure.

In between bouts of questioning, Smith dons an unusual helmet containing a video camera trained on his face. From the outside the elongated section at the base of the helmet makes Smith look like a long-beaked bird. On this “beak” are written the words “Freedom of Speech”. While wearing the helmet of free speech, Smith can speak his mind about his displeasure over the interrogations, but, at the same time, the helmet prevents him from seeing, so that his steps have to be guided by Pizano to keep him from trampling on the facts. The implication seems to be, as we all know from the 24-hour news networks, that freedom of speech does not necessarily entail adherence to facts.

During the performance Trevor Schwellnus proves himself a technical wizard. As director and stage manager his planning of camera angles and switching from shot to shot is masterful. His fading into and out of video footage on the back wall is impeccably done. You could say he plays the visual aspects of the show as a great pianist might play the piano. Lyon Smith’s soundtrack perfectly captures the unsettling mood of the piece. As actors, Pizano’s contributions tend to sound cold and scripted whereas Smith’s are so natural they seem completely impromptu. As we discover at the end, Smith’s responses were just as scripted as Pizano’s.

In only 65 minutes this remarkable performance piece sums up the contradictions in modern life ten years or more since the “War on Terror” was launched. What the piece shows so graphically is how we have become inured to the idea of unremitting violence committed in the name of safety without any evidence that we actually feel safer. In fact, the opposite seems true that the trust people once had in each other or in ideas or institutions has become more fragile if not entirely shattered. The point of the piece is to provoke or a Schwellnus says in his director’s note, to explore “The challenge of maintaining our humanity in trying times”. The play jolts us into realizing that “Lest we forget” is a phrase that should apply to our lives everyday, not just on November 11th.

©Christopher Hoile

*If you are looking for the Aluna Studio at 1 Wiltshire Ave., Unit 124, on Google Maps, it helps to switch to satellite mode to get a clearer view of how to get from Adrian Ave. into the courtyard of the building where the Studio is located.

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Beatriz Pizano and Lyon Smith;.Lyon Smith. ©2014 Trevor Schwellnus.

For tickets, visit www.alunatheatre.ca.

2014-10-31

What I learned from a decade of fear