Reviews 2015

✭✭✭✭✩

by David Lang, directed by Jim Findlay

International Contemporary Ensemble, The Theatre Centre, Toronto

February 26-March 1, 2015

“A Chamber of Secrets and Transformation”

Soundstreams is presenting the Canadian premiere of The Whisper Opera by American composer David Lang. ICE (International Contemporary Ensemble), who gave the world premiere of the piece at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in May 2013, performs it here with its original soloist, soprano Tony Arnold. Whether the work is actually an “opera” is a subject for debate. Irrefutable, however, is the fact that Lang and stage director Jim Findlay have created an aural and visual experience unlike any you may have ever encountered. Since conventional ways of listening to opera or watching theatre are of no use in appreciating this piece, the best way to experience it is to enter with a mind cleared of generic expectations and to allow the work simply to happen.

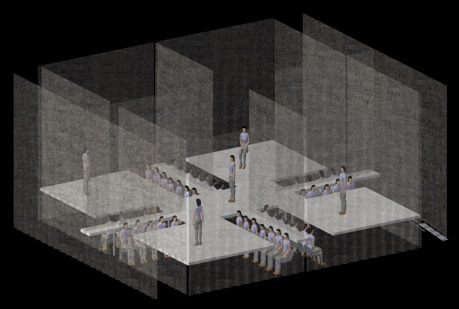

As one might guess from the title, a key aspect of the piece is quietness. For almost all of its sixty minutes the libretto is actually whispered, not sung, and the four accompanying instrumentalists play at the lowest volume possible. The point of the work is to force the audience to listen. To create the intimacy necessary for the piece to be heard, Findlay has designed a highly unusual performing space. The stage is raised to about collarbone level for the seated audience and is a square that has been subdivided into four smaller squares connected in the centre, rather like a stylized four-leafed clover.

In the trenches separating the four “leaves” are seats for 52 audience members. You are forced to face the leaf in front of you but can see the adjacent leaf to one side and a third leaf if you bother to turn your body far enough around in your seat. The fourth leaf directly behind you remains unseen. Given this set-up, one has to get used to the idea that, unlike conventional concerts, you will not ever be able to see the entire ensemble at one time and will only be able to see the soloist if she happens to wander into your line of sight. While this all seems very strange, one point being made is that intimacy also entails exclusivity, and exclusivity naturally entails exclusion. The other point is that you are always forced to listen to part of the music being made rather than always seeing it being made. Your mind thus must constantly link the seen and unseen to make a whole.

Gauzy translucent curtains surround the entire square and separate the leaves from each other. The blazing white floor of each leaf is set up for different instruments while suspended over each leaf is a bare light bulb that can lower and rise and a bass drum. These are the sole set decorations.

The performance began with the lights dimmed to about 50% and the two of the four musicians I could see spinning a cymbal on top of its stand. The only sound for me was the barely audible sound of the spinning. Then the musicians began whispering. The only word I caught echoing among them was the word “secret”. Tony Arnold then entered somewhere behind me humming and made her way around the four leaves several times as the musicians continued whispering. Then the musicians took up their instruments, and Arnold made her circuit again this time whispering the same words that the musicians had whispered. Musical phrases composed of one or two notes from each instrument reminded one of Anton Webern, but the repetition of the phrases linked the style more to Arvo Pärt. Since Arnold’s whispering, especially when she was not directly in front of you, was barely audible, what came across most was the interplay of the sibilants and plosives in English with the musical fragments.

A second phase was signalled by a change of lighting and a rotation of musicians. A flutist (Claire Chase) now replaced the cellist (Kivie Cahn-Lipman) on the leaf in front of us. She, like the other four musicians, began beating the suspended drum softly while others stroked their drums’ surfaces to create a sound much like waves breaking on a shore. During this phase the musicians began whispering again, taking care to look each one of us in the eye while repeating phrases like “I’m not crazy” or “I knew I could do it”. When the musicians returned their instruments to play, Arnold made her rounds again whispering in greater detail the same words we had heard from the musicians and also making sure to look every one of us in the eye as she did so.

After this phase came an exquisite musical interlude involving a dialogue between the flute and clarinet, each playing only one or two notes that kept bouncing back and forth between them. It was hard not to think of this as the twittering of birds.

After this interlude the flutist switched to a bass flute and the clarinetist (Joshua Rubin) to a bass clarinet. Then began the longest section of the piece. Arnold, her text on a music stand in front of her, whispered her phrases and with arms raised led the musicians to play in response at each every pause. The timbre of the lower register instruments blended perfectly with the timbre of Arnold’s whispered voice, the music acting as a kind of sigh after every phrase. The topic of Arnold’s whispers was fond memories, especially memories of love and light. At every mention of “light” the suspended bare lightbulbs lowered and suddenly glowed to full strength and dimmed again.

Rather than circulating among us has she had before, Arnold now remained in the centre of the square and directed each section of her whispered text to each on the four sections in turn. It may have merely been the ear becoming accustomed to listening to sound at such a low volume, but this section definitely seemed much louder than the previous one, which in turn seemed louder that the first. It is certain, however, that Arnold had now moved her whispering to the brink so that it occasionally included voiced phonation.

The final section began with a musician (Ross Karre), unseen to me, playing the glockenspiel. Not only was this the longest sequence of notes any musician had played thus far, the notes actually made up a melody. To this melody the other musicians joined in on flute, clarinet and cello – not adding missing notes as had happened earlier, but forming a continuo to support the melody. The final surprise was hearing Arnold’s lovely voice singing, the words unintelligible, but still singing off stage. The effect was as beautiful as it was mysterious, and it was a shock when this section reached its sudden end.

So what had we experienced? Was it an opera? As for an opera in any conventional sense, the answer would be no. Yet, people speak of Philip Glass’s Einstein on the Beach (1976) as an opera even though the singers sing only solfeggio syllables or the names for numbers. Lang’s use of a whispered text is very similar to Glass’s use of endlessly repeated spoken texts in Einstein at the Beach, except that Lang’s chosen fragments have greater meaning and seem to progress from expressions of doubt and worry to expressions of love and happiness. The passages in the earlier part of the piece where Arnold walks obsessively into and out of the four leaves of the performance space, reminded me of Beckett’s character May in his play Footfalls (1976), where the character walks back and forth and mutters to the actual, or perhaps remembered, voice of her mother.

Strictly speaking, the work is simply a staged chamber piece for four musicians and soprano. What that description failed to capture is the extent of the staging. The specially designed stage and its drapes make up a set. Arnold is wearing a costume design by Karen Young. And the lighting is not concert lighting but stage lighting that Findlay has intricately synchronized to reflect aspects of both the text and the music. Given this level of theatricality, the term “opera” is probably the closet to describing the work’s genre, making the title “whisper opera” exactly right.

Lang is clearly pushing the boundaries of what opera is but that is what experimental works do. Lang is not writing for those who think of opera only in terms of cigarette-rolling gypsies or parades of elephants. Instead, he is writing for those lovers of new music who are open to entertaining more expansive definitions of genre.

As for the work’s effect, it is a piece, not unlike those of Glass or Pärt, that the listener has to give himself to. Any resistance will cause the work to seems boring because it doesn’t fulfill any particular generic expectations. If you do give yourself to the work, you find that it take you on a journey from silence to song, from fragments to melody. Arnold as the central figure moves from being haunted by the texts she repeats to being in charge of the musicians who accompany her to finally being independent of the stage entirely. This depiction of her emergence from enchainment to empowerment to freedom is very powerful. It is supported by the change in texts from fragments to sentences to song and in the music from fragments to antiphonal response to melody and accompaniment.

The Whisper Opera will obviously not be for every taste, but for the open-minded and musically adventurous it is an hour-long journey they will be willing to take. The best way to experience how Lang’s music becomes part of you is to avoid conversation afterwards and seek out a quiet place. There you will find that you brain is still replaying sections of the work. Despite its short running time, Lang thus demonstrates how a work of art, in this case a musical-theatrical experience, if closely attended with ear and eye, becomes part of human memory.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: Ross Karre, Tony Arnold and Claire Chase; stage design and seating plan; Claire Chase and Tony Arnold. ©2013 Armen Elliott.

For tickets, visit http://actingupstage.com.

2015-02-27

The Whisper Opera