Reviews 2015

✭✭✭✭✩

by Christoph Wilibald Gluck, adapted by Hector Berlioz, directed by Marshall Pynkoski

Opera Atelier, Elgin Theatre, Toronto

April 9-18, 2015

Choeur: “L’amour triomphe!”

Opera Atelier must be one of the few opera companies in the world to have presented all three versions of Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice opera in a span of less than twenty years. In 1997 OA presented Gluck’s first version, Orfeo ed Euridice of 1762 written to an Italian libretto. In 2007 OA presented Gluck’s own 1774 revision of his work to a French libretto. In that version, renamed Orphée et Eurydice, Gluck’s most notable concessions to French taste are the rescoring of the castrato role of Orpheus for haute-contre (a male with a high tenor) and the major expansion of ballet sequences.

Now OA is presenting the version of Orphée et Eurydice created by Hector Berlioz in 1859. In Paris, concert pitch had risen steadily since 1774 so that the role of Orpheus now lay too high for an haute-contre. Giacomo Meyerbeer suggested that Berlioz revise the role for contralto Pauline Viardot (1821-1910), famed as a singer and actor and a composer in her own right. Berlioz’s version uses the key scheme and some of the orchestration of the Italian version but retains most of the additional music of Gluck’s French version. OA and the Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra deviate from Berlioz’s version by presenting the final celebratory ballet music. In his “Conductor’s Notes”, David Fallis points out that Berlioz’s explanation was that “the resources of the Théâtre Lyrique did not allow for their execution”, but, as Fallis adds, “since no one would make the same suggestion of Opera Atelier, we have reinstated them”.

Anyone who knows the original story of Orpheus may wonder how such a tragic tale in Greek mythology could end in “celebratory music”. On the day of her wedding to Orpheus, the greatest of all poets and musicians, Eurydice was attacked by a satyr. In her effort to escape, she stepped on a nest of vipers are was fatally bitten. Orpheus’ grief was so great, the gods took pity on him and said he should journey to Hades and plead for her to be returned to life. Orpheus does so and his music so moves Hades the ruler of the underworld and his wife Persephone that Hades allows Orpheus to take his wife back to the land of the living on one condition – he must not look back at her during the entire journey. Just as the two were about to reach the upper world, Orpheus’ anxiety overcame his reason, he looked back and lost Eurydice forever.

Theatre in the 18th century was more interested in depicting what should happen than what did. That’s why Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet and King Lear were all revised in that period to have happy endings. So it is with the story in Gluck’s Orpheus which remains the same in all three versions. The opera begins with Orphée mourning the death of his wife. Then Amour, or Cupid, descends and tells Orpheé that the gods have taken pity on him. It is Amour, not Hades, who tells Orpheé of one stipulation of not looking back. In ballet form Orphée pleads with Pluton and Persephone, who grant his wish. During their ascent to the upper world, Eurydice becomes so distraught at what she perceives as Orphée’s indifference that she begins to die of a broken heart. To save her Orphée does look back at her but it is too late. Luckily, Amour again intercedes and brings Eurydice back to life because Orphée has proven how true his love is.

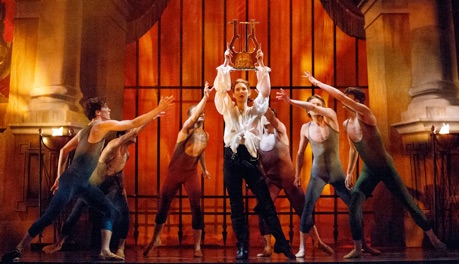

OA’s production of the Berlioz’s version is essentially a remount of its 2007 production only with Berlioz’s revised score and a mezzo-soprano as Orphée. Otherwise, Gerard Gauci’s painted drops and Margaret Lamb’s costumes, Jeannette Lajeunesse Zingg’s choreography and Pynkoski’s stage direction remain the same. Contrary to what one might expect, OA, thus, does not present a vision of what the opera would have looked like in 1859 with its costumes and backdrops inspired by ancient Greece. Instead, OA’s 2007 production positions itself in look and style halfway between the 18th and the 19th centuries. The men wear tights, knee-high boots and blousy shirts that give them the air of buccaneers. The women wear petticoated ankle-length gowns topped with overbust corsets very much as in 19th-century ballet. Amour, however, is costumed as if he were an 18th-century boy not unlike the young Mozart.

In his direction, Pynkoski seeks a point where the stylized gestural language of the baroque was transforming itself into melodramatic tropes of the 19th century. In her choreography of the dances that make up at least half of the work, Jeannette Lajeunesse Zingg creates beautiful patterns in the baroque style, but includes 19th-century pointe work in “Dance of the Blessed Spirits” and floor-oriented rolls for the Furies from the 20th century.

Compared with Gluck’s 1774 version, Berlioz’s revised score is imposing but its orchestration more austere as if Berlioz were highlighting Gluck’s importance as a reformer with his emphasis on purity of line and lack of ornamentation. David Fallis led the 35-member Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra in a stirring account of the score, with a particularly hair-raising “Dance of the Furies.” Fallis found in the Act II music in Hades numerous pre-echoes of Mozart’s Don Giovanni and Requiem of 1791 as well as intimations of Berlioz’s own La Damnation de Faust of 1846. In fact, it is impossible to see this production of Gluck’s Orphée where a young man rescues a young woman from captivity, where his music charms savage spirits, where he must undergo a test of his love and where a deus ex machina is always available for help, without thinking of Mozart’s The Magic Flute.

Canadian mezzo-soprano Mireille Lebel makes her role debut as Orphée. While her lower register does not always cut through the orchestra, her voice in its middle and upper registers soars above it with a creamy tone and gleaming top notes. Lebel triumphs in Gluck’s showpiece aria, “Amour, viens rendre à mon âme,” here sung a cappella, to which conductor David Fallis has added Viardot’s original ornamentation of octave-length leaps, trills and high notes that Lebel tossed off with thrilling panache. In terms of acting Lebel has not quite made the stylized gestures feel like natural expressions of emotion, but it is still a very creditable performance.

OA favorite, American soprano Peggy Kriha Dye, who sang Eurydice in 2007, returns to the role and lends it even greater depth. She makes Eurydice’s death from heartbreak in Act III especially moving. Soprano Meghan Lindsay with her bright, sparkling tone is ideal as the ever-optimistic deus ex machina Amour.

The added final ballet is the same as that in 2007 in turning the stage into an enormous Valentine’s Day card with dancers holding out letters spelling “L’Amour triomphe,” the words to the final chorus. After the curtain calls, when Pynkoski has the performers reprise the chorus and ballet, he takes his concept even further over the top. Dancers holding out letters spelling “Immortal Hero” that when turned around spell “#OAorpheus,” the Twitter address for the show. This is rather a cheeky move, but then OA has been on a high ever since Pynkoski and Zingg directed Mozart’s Lucio Silla at La Scala in February this year. The audience was delighted and more than happy to allow the company a bit of giddy self-promotion.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: A version of this review will appear later this year in Opera News.

Photos: (from top) Mireille Lebel (Orphée) and Peggy Kriha Dye (Eurydice); Mireille Lebel (Orphée) and artists of the Atelier Ballet; Artists of the Atelier Ballet. ©2015 Bruce Zinger.

For tickets, visit www.operaatelier.com.

2015-04-13

Orphée et Eurydice