Reviews 2015

✭✭✭✭✩

by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted by Michael Healy, directed by Miles Potter

Stratford Festival, Tom Patterson Theatre, Stratford

May 27-October 3, 2015

Dr. von Zahnd: “I’m the one who decides who my patients think they are!”

One of the surprises of the Stratford Festival’s 2015 line-up is Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s 1962 comedy The Physicists (Die Physiker). Except for Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot from 1953, the Festival has seldom staged absurdist plays or plays influenced by absurdism. It’s never even staged Beckett’s two other full-length plays Endgame (1957) or Happy Days (1961). As for Dürrenmatt, the Festival last staged one of his plays in 1981, a great production of The Visit starring William Hutt and Alexis Smith directed by Jean Gascon. It is good, therefore to see the Festival explore other plays by the Swiss playwright, especially when the production and acting are of such a high level.

The play is set in a Swiss villa converted into an insane asylum called the Les Cerisiers Institution, (“cerisiers” meaning “cherry trees”). The institution is presided over by the indomitable hunchback Fräulein Doktor Mathilde von Zahnd (Seana McKenna), who is the last in a long line of famous physicians and psychiatrists who, sadly, all went mad before they died. Les Cerisiers currently has only three patients, all of whom are physicists or at least believe they are physicists. There is Herbert Georg Beutler (Graham Abbey) who believes he is Sir Isaac Newton (1643-1727) and dresses in a wig and 18th-century garb. There is Ernst Heinrich Ernesti (Mike Nadajewski), who believes he is Albert Einstein (1879-1955) sports wild hair and constantly plays the violin for relaxation.

The third patient is Johann Wilhelm Möbius (Geraint Wyn Davies). Möbius shares his last name with the famous German mathematician August Ferdinand Möbius (1790-1868), who first described an object since known as the Möbius strip, a two-dimensional surface in the form of band with only one side. Paradoxical as the object may seem, it is simple to make and its properties have had practical applications in electronics, physics, chemistry and nanotechnology. Dürrenmatt’s character Möbius is like that band, appearing to have two sides, but in reality having only one, and his Möbius’ theory is like that of his predecessor, highly abstract but rich in practical applications.

The Möbius in the play does not believe he is someone else. Rather his delusion is that King Solomon of the Bible appears to him on a regular basis and dictates the “Principle of Universal Discovery”, the modern “theory of everything” that scientists have been searching for that will provide one coherent explanation for all physical aspects of the universe.

Two other events occur in Act 1. First, Lina Rose (Jane Spidell), who has divorced her husband Möbius, has brought their three children and her new husband Oskar (Sean Arbuckle) to meet Möbius and say goodbye before she and the family depart for the Mariana Islands. To make this parting less painful, Möbius becomes abusive to his wife and children and claims that King Solomon has directed him to do so. Thus, the nominally insane Möbius intentionally feigns insanity which suggests that he cannot actually be insane. Second, Möbius’ personal nurse Monika Stettler (Claire Lautier) admits she is in love with Möbius and has concocted a plan to help them escape the villa and start a new life together.

At the end of Act 1, the play looks like a witty but not especially innovative demonstration of one of the questions that intrigued authors and psychiatrists in the 1960s, namely “Who has the authority to say who is sane or insane?” and “Is not insanity the appropriate response to life amidst the insanity of the outside world?” These ideas are found in R.D. Liang’s The Divided Self (1960), Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilization (1961) and in novels like Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962).

Yet, what may be the end point in a play about psychiatry like Peter Shaffer’s Equus (1973), is just the starting point for Dürrenmatt’s The Physicists. After the set up of Act 1 and the basic questions it poses, Act 2 presents us with one revelation or plot twist after the next. Here Dürrenmatt moves into questions that are especially pertinent today. “What should the relationship be between science and politics? What should the relationship be between science and commerce? Can science ever be ‘pure’ if it can be used to bring about good (nuclear power) or ill (atomic bombs)?”

The Physicists is a forerunner of the kind of intellectual comedy involving famous historical figures that we now associate with Tom Stoppard. Stoppard’s first play to use such characters was Travesties (1974) set in Zurich when James Joyce, Lenin and Tristan Tzara were all living there. But while Travesties is enormously clever, The Physicists has something that Stoppard’s play notoriously lacks – an emotional centre.

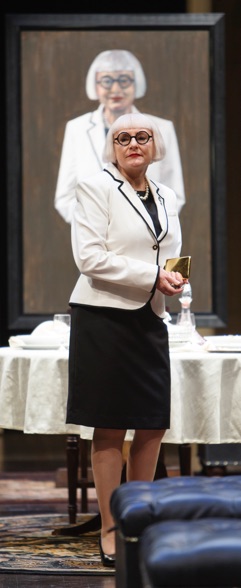

If Möbius is the play’s main representative of knowledge, Dr. van Zahnd is is main representative of power. The role is ideal for Seana McKenna whose dry delivery of the self-obsessed doctor’s more outrageous statements makes them even funnier. She is able to have van Zahnd blithely refer to the gallery of her mad forebears without a hint that she may not be the exception she thinks she is. In fact, McKenna helps us to realize that van Zahnd’s absolute certainty about everything may not be the sign of a mentally healthy human being.

Graham Abbey is suitably self-assured as “Newton” and Mike Nadajewski humble as “Einstein” in Act 1 and both ably switch into a more aggressive personae in Act 2. Jane Spence gives a remarkable performance as Lina Rose, perfectly poised on the edge between comedy and pathos. Claire Lautier is a seductive nurse Stettler while Randy Hughson is so funny as the hangdog detective one wishes Dürrenmatt had made the part longer.

Peter Hartwell’s set is most notable for a wonderful lighting fixture on centre stage that cleverly looks both like planets circling a sun or like atomic particles orbiting a nucleus. In adapting the text, Michael Healey has thankfully confined himself only to punching up some of Dürrenmatt’s humour and to updating technological references to the computer age. He has otherwise left intact Möbius’s “Principle of Universal Discovery” and Dürrenmatt’s surprising foresight about the place of science in the modern world.

Not only is The Physicists a treat for the audience, it also seems to be a treat for the actors who all seem to be enjoying the chance to act in the kind of modern, intellectually playful work that is seldom on the agenda at Stratford. There are more plays in this vein and let’s hope the Festival seeks them out. Meanwhile, theatre-goers should make sure to see this laughter-provoking, thought-provoking show.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Rylan Wilkie, Mike Nadajewski, Geraint Wyn Davies, Graham Abbey and Victore Ertmanis; Seana McKenna as Dr. van Zahnd; Geriant Wyn Davies as Möbius. ©2015 David Hou.

For tickets, visit www.stratfordfestival.ca.

2015-06-22

The Physicists