Reviews 2016

✭✭✭✩✩

by William Shakespeare, directed by Graham Abbey

Groundling Theatre, Coal Mine Theatre, 1454 Danforth Ave., Toronto

January 28-February 20, 2016

Time: “I, that please some, try all, both joy and terror

Of good and bad, that makes and unfolds error”

The Groundling Theatre Company makes its debut with a intimate production of The Winter’s Tale on the tiny stage of the Coal Mine Theatre. The ten-member company is an amazing gathering of stars from Toronto and the Stratford and Shaw Festivals. To see them working as an ensemble on one of Shakespeare’s most profound, most poignant plays is a pleasure in itself and a fantastic luxury for an audience that can number at most 100. Director Graham Abbey draws excellent performances from much of the cast but slightly reorders our experience of the action which confuses the play’s import and themes

Abbey begins the action in Shakespeare’s Act 5, where King Leontes of Sicilia (Tom McCamus) is still ruing the rash actions he took sixteen years earlier that caused the deaths of his son Mamilius (Calum McAlister) and his wife Hermione (Michell Giroux). Set at some point between the 1930s and 1950s by costume designer Michael Gianfrancesco, Leontes is punishing himself by watching home movies of Hermione, Mamilius and himself in the happy time long past. Paulina (Lucy Peacock), who always believed Hermione innocent of his accusation of adultery, is there still to upbraid him for his actions, a criticism he welcomes as a form of penance.

Presenting the first part of the play as a flashback may seem like an innocent enough ploy except that it has a negative effect on the themes and structure of the play. First of all, from a purely practical point of view, Leontes’ memory of the past at the start of Act 5 cannot include Act 4 which is set in Bohemia and of which Leontes knows nothing until the end of Act 5. Second, the flashback set-up places the subsequent action in Leontes’ mind when Shakespeare makes clear we are watching no one person’s memory but the doings of Time itself. Abbey’s set-up subordinates Time’s important speech to Leontes’ mind, when, in fact, it is essential that we see that Leontes is subject to Time. Time is, after all, the active agent of the plot as it says of itself: “I, that please some, try all, both joy and terror / Of good and bad, that makes and unfolds error” (IV,1). Finally, the notion of Leontes watching home movies of Hermione and Mamilius means their images have already been captured in art which ruins the surprise and entire point of the statue scene at the end since Leontes already has the facsimile of a living moving Hermione before his eyes.

In order to make the experience of the play more comfortable in the cramped space of the the Coal Mine’s Theatre’s present location and in order for only ten actors to play it, Abbey has cut the text. In general, his excisions are all well considered, but he noticeably omits all the passages that link The Winter’s Tale to the other four plays known as Shakespeare’s “romances”. All five of the romances – Pericles (c. 1607), Cymbeline (1610), The Winter’s Tale (1610), The Tempest (1611) and The Two Noble Kinsmen (1613) – are characterized by divine intervention and the themes of time and art.

Abbey at least preserves the character of Time in the person of musician George Meanwell. Indeed, his live accompaniment, especially in transitions from scene to scene, does help reinforce the idea that Time is guiding the action. Unluckily, Abbey cuts sections of the play that are key to understanding its larger meaning. He omits the scene (III, 2) of divine intervention when Cleomenes and Dion return from the Temple of Apollo at Delphi with the oracle’s verdict on Hermione proclaiming her chaste and Leontes a tyrant. The fact that Leontes rejects this divine verdict is the height of his hubris as a tragic character.

Abbey also omits two central passages relating to nature and art, the subject that The Winter’s Tale so carefully explores. The first of these passages (IV, 4) occurs when Perdita gives flowers to the disguised Polixenes and Camillo. Abbey shows the flower-giving but omits Polixenes commentary on flower-breeding that is one of Shakespeare’s most profound statements on art. Polixenes tells Perdita: “This is an art / Which does mend nature, change it rather, but / The art itself is nature”. This is a rebuttal to Plato’s view (The Republic, Book X) that art is inferior to nature since it identifies the creativity of man with the creativity of nature.

The second passage is the description (V, 2) of the carving of the statue of Hermione in Paulina’s keeping. This passage spoken by the Third Gentleman links up directly with that in Act 4. The Gentleman refers to the statue as “a piece many years in doing and now newly performed by that rare Italian master, Julio Romano, who, had he himself eternity and could put breath into his work, would beguile Nature of her custom, so perfectly he is her ape”. This is important because it emphasizes that the statue actually is a statue, and not, as so many would like to believe, merely the real Hermione in some sort of suspended animation. What happens at the end is supposed to be a miracle and that is why Paulina tells the group about to see art become nature, “It is required / You do awake your faith”. Shakespeare is describing how something that is art, like a statue or like a play, becomes real in the mind of the viewer – something that Coleridge would later call the “willing suspension of disbelief”. To omit the passages about art and nature is to miss the true import of the story.

Nevertheless, there is a great advantage to seeing The Winter’s Tale in such a small space as the Coal Mine Theatre. The intimate space means that the actors can deliver Shakespeare’s verse in a conversational tone. Perhaps, unsurprisingly, since the words do not need to be projected, they and their meaning seems clearer. The Winter’s Tale was, after all, written for an indoor theatre like the original Blackfriars. That is one reason why a conversational tone seems so apt.

While Abbey draws generally fine performances from the cast, there is one overall failing that is hard to ignore. Between Act 3 and Act 4, Time steps in to inform us that sixteen years have elapsed. Yet, of the characters who appear both before and after Time’s announcement, only Lucy Peacock as Paulina and Robert Persichini as the Old Shepherd make any attempt to show a change in age.

Tom McCamus’s Leontes, in particular, should appear ravaged by sixteen years of grief and repentance yet here seems as energetic as when we first meet hime. McCamus does depict the onset of Leontes’ fit of jealousy well, but the best performances should show that Leontes is aware he is acting rashly but, like a sick man, can’t prevent himself from doing what he does.

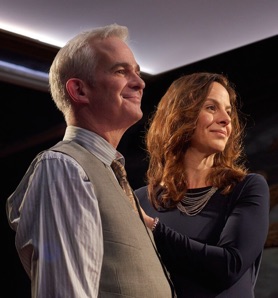

Michelle Giroux gives a fine account of Hermione and her nobility of demeanour with its underpinning of bewilderment and sorrow in face of husband’s irrational accusations. She also is seductive enough at the beginning that someone like Leontes could put a false contraction on her natural persuasiveness in making Polixenes stay if one so wished. Lucy Peacock is an excellent Paulina, a role one hopes she will play sometime at Stratford, bursting with rage mixed with sadness at Leontes and the tragedies he has caused. Her finest scene is that with McCamus when she announces Hermione’s death and they both collapse in grief and despair.

Patrick Galligan is a well-spoken Polixenes, who flies into his own blind rage at his son and Perdita just as Leontes had earlier at Hermione. In both Sicilia and Bohemia, Roy Lewis is a stalwart source of reason as Camillo, who tries to calm both kings when he sees that only emotion guides their actions.

While it is a pleasure to see Brent Carver on stage again and so close up, it is hard to know what he is doing in either of his roles as Antigonus, Paulina’s aged husband, or as Autolycus, the chief thief and rogue of Bohemia. Abbey omits one of Shakespeare’s most famous stage directions, “Exit, pursued by a bear” that refers to Antigonus’ misfortune on landing in Bohemia. Instead, Abbey appears to have Carver act out both the roles of Antigonus and the bear, but the way Carver enacts the scene looks more like Antigonus is transforming into a werebear himself than that he is being pursued. As Autolycus, Carver has several songs to sing, very suitable for such a figure and well sung, but Carver’s characterization makes Autolycus seem more mentally distrait than wily and cunning.

The chance to se so many fine actors playing Shakespeare in such an intimate space will be reason enough for many to attend. Nevertheless, the general impact of the play is neither as intellectually or emotionally satisfying as others in the past. Of the many productions I have seen. The one directed by the late, much lamented Brian Bedford at Stratford in 1998 still remains the most emotional I have ever seen. The reconciliation at the end where all the main characters acknowledge their faults and forgive each other was a beautiful depiction of the power of truth and forgiveness to help re-form a broken society. Abbey’s production never approaches that power, likely because he chooses to view the action as a domestic rather and universal tragedy that the characters must face. Yet, with Groundling Theatre Company’s access to such actors as these, one looks eagerly forward to whatever project it next undertakes.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

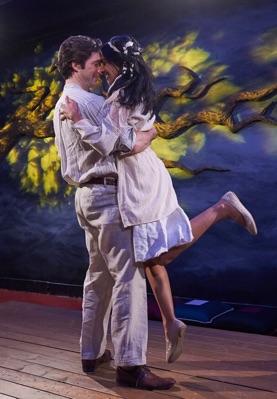

Photos: (from top) Tom McCamus as Leontes and Lucy Peacock as Paulina; Patrick Galligan as Polixenes and Michelle Giroux as Hermione; Charlie Gallant as Florizel and Sarena Parmar as Perdita. ©2016 Michael Cooper.

For tickets, visit www.coalminetheatre.com.

2016-01-29

The Winter's Tale