Reviews 2016

✭✭✭✭✩

by Sally Clark, directed by Tyler Séguin

Thought For Food, Theatre Passe Muraille Backspace, Toronto

January 29-February 14, 2016

Nun: “You don't need to accept everything as true, you only have to accept it as necessary”

In 2014 Tyler Séguin directed a thought-provoking production of Vaclav Havel’s play The Memo for Though for Food. Now he and the company are back with another absurdist play, this time from Canada – Sally Clark’s The Trial of Judith K. from 1989. As the title suggests, Clark’s play is an adaptation of Franz Kafka’s classic novel The Trial (1925), but with Kafka’s protagonist Josef K. reimagined as a woman, Judith K., and the setting shifted from 1920s Prague to 1980s Vancouver. Though adhering very closely to the plot of the novel, Clark’s swapping the protagonist’s gender and that of most of the other characters gives Kafka’s general examination of the futility of existence a more specifically feminist slant. Why this change should have such an effect is as intriguing now as it was when Clark first adapted the novel.

As in Kafka’s novel, Judith K. (Stephanie Belding), who works in a bank, wakes up on the morning of her 30th birthday to find two men (Andrew Knowlton and Scott McCulloch) in her bedroom who tell her she’s under arrest. Her landlady Edna Block (Toni Ellwand), female in both Clark and Kafka, seems to be in cahoots with the authorities. Judith, as in Kafka, is never told what crime she is charged with, but is also told she can continue with her work and everyday activities as long as she reports for interrogation regularly at a specified address.

Judith does attend the court, which is in session in a derelict building, decries the situation and offends the Magistrate (Scott McCulloch). Later back at the bank, Judith discovers that the two men who arrested her are being flogged for asking for bribes. In the novel, Josef K. is visited by his uncle; in the play Judith K., separated from her husband, is visited by her sister-in-law Deedee (Cara Pantalone), who tells her who the best lawyer for her case is. Judith visits the lawyer, who is male in Kafka, Theadora (Helen Juvonen), a bedridden consumptive with a personal attendant, female in Kafka, Ted (Patrick Howarth), who seems to be romantically involved with Theadora although the lawyer herself appears to be rather more a prostitute than a lawyer. As in Kafka, Judith is strongly but unwillingly attracted to the attendant and they begin an affair.

Meanwhile, Judith’s position at the bank worsens due to her lack of attention and her vain attempts to seek advice. The court painter (Scott McCulloch), who is male in both Clark and Kafka, tells her that no one accused has ever been acquitted and she discovers that her own landlady (an unacquainted man in Kafka) has been fighting her own case for six years with the help of six different lawyers. In Clark, a Nun (Cara Pantalone), substituting for the priest in Kafka, recounts the parable “Before the Law” (“Vor dem Gesetz”) before Judith is led off for sentencing.

The single greatest difference that Clark makes to Kafka’s tale is by making the lawyer’s attendant a serial killer. In Kafka, Josef K. notes that a man and woman are having sexual relations while the Magistrate speaks. In Clark, Judith K. notes that a man, Ted, strangles a woman to death. The Magistrate asks Ted if he has killed any other women, Ted says he has and tells the Magistrate where their bodies are. Rather than punishing him, the Magistrate does not charge Ted because he has given information that will help solve a crime.

Later it is this same man, who is attendant on Theadora, with whom Judith has an affair. She is attracted to him and the more she gives in the more information he tells her about the court. Ted tells her that he is not, in fact, a serial killer and that all the women he “killed” only were pretending.

Symbolically, Judith’s attraction to Ted is the least understandable aspect of the play. More understandable is Clark’s portrayal of Judith’s female colleague, male in Kafka, who takes advantage of Judith’s distractions to steal her clients and advance herself in the bank. With this Clark is suggesting, as does Caryl Churchill in Top Girls (1982), that women who strive to fit into a male-dominated hierarchy will also adopt a male model of behaviour.

Designer David Poholko has created a very clever set of two three-sided pillars that can be turned to represent different places, a door in a door frame, a bed which can be turned to represent the Magistrate’s desk and a side table. In scenes changes under Jareth Li’s disorienting lighting, the actors moves these pieces about until they reassort themselves to represent a new location. Through this simple method Séguin lends a dreamlike quality to the action, very appropriate for a nightmare of paranoia that Kafka and Clark reveal as everyday life.

Kafka’s original novel used its satire of the obtuseness of bureaucracy, particularly of the law, as a metaphor for the meaninglessness of existence and our feeling of dread at realizing that we have been condemned by being born to live out this sentence for life. Clark’s gender-swapping still carries Kafka’s original intent but adds an element that dominates it. Because Judith is a woman, she is born into a society where she is condemned to be undervalued and objectified by men from which there is no escape. The Nun’s advice, “You don't need to accept everything as true, you only have to accept it as necessary” is as depressing as Judith (like Kafka’s Josef) says it is because it implies that nothing will change. In Clark, Kafka’s story becomes a nightmare vision of what a world unenlightened by feminism would be like.

Tyler Séguin has drawn fine performances from the entire cast. Belding is excellent as an intelligent, ambitious young woman who wakes up one day to find that her intelligence and ambition are no longer of any use. Belding finds humour not only in Judith’s initial naïveté in assuming that there a purpose to her life as well as in her gradual realization that each new tip she is given will only lead to a dead end. Belding also makes frighteningly real the sudden shift from the absurdist levity of the majority of the play to deadly earnestness at the end.

The other six actors, who play three or even four characters each, are all successful at keeping them completely distinct. Patrick Howarth’s oily Inspector and manic Flogger are nothing like the enigmatic Ted. Howarth manages to lend Ted enough suavity that it is almost believable that a woman as smart as Judith could fall for his charms.

Toni Ellwand makes sure her two main characters, Edna Block and Mrs. Voight, are completely different. The first is frumpy and cowardly, the second cold-hearted and sneeringly superior. Helen Juvonen’s Miss Lang is mousy but calculating in contrast to her lubriciously seductive Theadora. Cara Pantalone’s best role is probably Judith’s abrasive sister Deedee, Scott McCulloch’s likely the lascivious painter Pollock and Andrew Knowlton’s the sleazy would-be borrower Brazier.

Séguin encourages the actors to play the piece in the outsized manner of sketch comedy to make this absurdist play laugh-out-loud funny before it hits you with its shockingly dark ending. Sally Clark herself was in the audience on opening night and seemed pleased to see that her adaptation of Kafka’s great novel is still so effective after 27 years.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

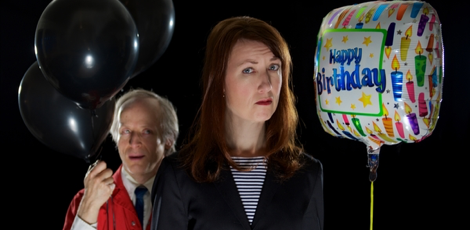

Photos: (from top) Scott McCulloch and Stephanie Belding; Stephanie Belding as Judith, Helen Juvonen as Theadora, Toni Ellwand as Edna and Patrick Howarth as Ted. ©2016 John Gundy.

For tickets, visit http://thought4food.ca.

2016-01-30

The Trial of Judith K.