Reviews 2016

✭✭✭✩✩ / ✭✭✩✩✩

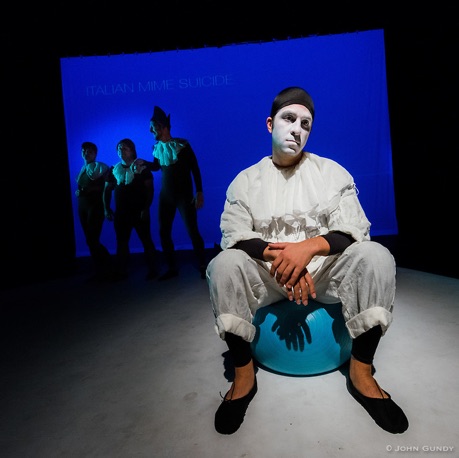

by Bad New Days, directed by Adam Paolozza

Bad New Days, The Theatre Centre, 1115 Queen St. West, Toronto

October 8-23, 2016

“How do you mime the intangible?”

It is no pleasure to say that the new double bill from Bad New Days is a major disappointment. Adam Paolozza, director and performer for both, has done such fine work in the past as in Spent seen in 2013 and The Double seen in 2012, that it is surprising that these two new works should be so ill-conceived. Both plays, Italian Mime Suicide and Three Red Days, feel more like rough drafts for plays rather than finished products with Italian Mime Suicide the more successful of the two.

The programme begins with the 25-minute-long Three Red Days. The piece is based on an event in the life of the Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-75). In 1948 he and several other composers in the USSR were denounced for writing “formalist” music, a code term meaning music written under a perceived Western influence. The composer was called in by the NKVD (part of the secret police) for interrogation on a Friday and told he must report back on Monday, meaning he would be formally arrested and likely exiled. He and his wife spent three anxious days of waiting before Shostakovich returned only to find that all charges had been dropped and that his interrogator had himself been arrested.

This makes a great anecdote and is related in the Director’s Note in the programme. Not having read the programme beforehand, I will admit that I didn’t have a clue what the piece was attempting to show. Needless to say, an audience should not have to read the programme in to understand a play. The piece should stand on its own.

The following description of the plot is based almost entirely on my reading of the programme notes and not on viewing the performance. All I could make out was that three men (Rob Feetham, Paolozza and Viktor Lukawski) were waiting nervously in an office while a Soviet official (Miranda Calderon) periodically looked at a file, laughed and turned on or off an invisible radio or phonograph playing Shostakovich string quartets. After this introduction the long middle section shows the three men doing miscellaneous activities – shaving, scratching, falling down – in time to the music. Calderon returns in a 1940s-style dress and is sometimes separated from Paolozza, leading us to believe that she may be Mrs. Shostakovich. In various mime stunts suitcases that were light suddenly become heavy and then become light again. The piece ends with the three men back in what is perhaps a different office, the official acting in the same manner. It ends with the official donning a large mask of Stalin and the three doing obeisance to it.

Paolozza says that the two mime pieces are non-narrative, but that is not really the case with Three Red Days which has a clear beginning and end. Since the group creation never depicts Shostokovich’s interrogation, we don’t know even which of the three he is. I assumed that two of them might be Sergei Prokofiev and Aram Khachaturian, composers who were also attacked by the government at the same time. Reading the programme, however, reveals that all three men are Shostakovich, something which is certainly not clear from the performance. It also raises the question why three actors are playing the same character. They are not different aspects of Shostokovich’s personality as are the four Glenn Goulds in David Young’s Glenn (1992), since the three mostly just mirror each other’s activities. It is difficult then to see what the point of this triplication is.

It is also unclear what the unconnected middle episodes are supposed to represent. In hindsight one can see that Bad New Days is trying to shown how everyday life becomes warped by waiting in a climate of fear. Fears of fleeing and separation are shown once we’ve determined that Calderon must be Shostakovich’s wife Nina. The problem is that these scenes are not specific to the situation. Everyday life becomes warped for anyone living in fear not simply in the Soviet Union.

The deeper problem is that Three Red Days completely ignores the essence of the conflict between Shostakovich and Stalin – that is, how a composer can remain a creative individual under a totalitarian regime that seeks to repress individual expression as a threat to the state. That subject could be a rich vein of thought for mime to explore, more than simply the frantic thoughts of people waiting. British playwright David Pownall wrote a play directly on this topic in his Master Class (1982) which imagines a direct confrontation between Shostakovich and fellow composer Sergei Prokofiev on the one side and Stalin and his culture minister Andrei Zhdanov on the other.

The most imaginative scene in Three Red Days is when the official opens a suitcase and begins pulling out metres of recording tape while the three surprised men suddenly start pulling recording tape out of themselves. This is a great image of the three men realizing to their dismay that they have been under government surveillance.

The most surprising flaw of Three Red Days is that it is not executed all that well. The three mimes are supposed to synchronize their actions with each other and to the music, but more often than not they are not quite in sync and their performances so lack precision that it seems under-rehearsed.

Italian Mime Suicide is altogether more successful. This piece is also based on a true story. Paolozza states in his Note that in 2003 a friend told him about a story he’d read: “An Italian mime jumped off a building claiming that no one appreciated his art”. Paolozza says his reaction was “ a simultaneous sense of pathos and of ridiculousness”. Throughout Italian Mime Suicide we hear a recorded voice make pronouncements in Italian about the theory and importance of mime while a translation in English is projected on the back wall. The actions that occur after these pronouncements seem to capture both the pathos and ridiculousness of the art form.

The first of these, as a kind of introduction to the spirit of mime as play, is Feetham performing a number of hilarious pratfalls in his attempt to move a Swiss ball. Paolozza, who plays the doomed Mime, comes out in archetypal mime gear and puts on his grease paint in front of us, after which he imitates the various expression of people in the audience. Later we see two figures suggesting the look of commedia dell’arte characters – a father (Lukawski) wearing a bicorne and a mother (Calderon) holding a baby, while a young gorilla (Feetham) plays about at their feet striving for attention. This juxtaposition neatly suggests that a mime is a person who expresses as art what the wild person inside us represses.

In subsequent scenes we see the lonely Mime join the circus and eventually leave it to strike out on his own. At one point he literally tries to catch his place in the spotlight as the spotlight moves from the stage and up the back wall. The most inventive scene in the piece presents a morning talk show with a jolly male and female host (Lukawski and Calderon) who make inane banter and occasionally ask the inevitable sidekick (Feetham) for a comment. The Mime is a guest on the show, supposedly to be interviewed about why he left the circus and why his career has gone downhill. As one might expect, neither host is actually interested in understanding the Mime. All they really want is for him to perform the clichéd mime routine of being trapped in a glass box. The brilliance of the scene comes from the fact that all four actors lipsynch to prerecorded words, a fact that underscores the popular imagination’s pre-existing views of what mime is all about.

After both a comic and then a poignant depiction of the Mime’s suicide, the 35-minute-long show ends with a staged talk-back between Lukawski and Paolozza as themselves. Unlike the earlier talk-show, the actors speak live in their real voices. The notion of a staged talk-back has both plusses and minuses. On the one hand, theatre talk-backs are events ripe for satire. Why should actors have to explain themselves after a performance? Shouldn’t the performance itself be enough? Beyond this, in a show about the death of a mime, the talk-back by using real speech basically shows us speech killing mime right before our eyes.

On the other hand, the mimed play has ended so strongly, it is almost painful to have to listen to the actors speaking. While the creators may be making fun of the idea of actors explaining the play to the audience, the actors do actually explain the play we have just seen. We learn that they have decided to make the death of this particular Italian mime signify the death of mime as an art form in general. Ironically, of course, every word the two speak about the show takes us further away from the essence of mime.

Thus, I both understood why Bad New Days ended the piece in such a daring way and I disliked it at the same time, but this may, in fact, be the reaction the company is seeking. Overall, Italian Mime Suicide has a fascinating premise that it does not fully explore. I would certainly like to see more about how the child comes to the idea of becoming a mime in the first place. During the talk show we hear about some of the Mime’s failed solo shows after he leaves the circus. It would be better to see some of them. The voice-over and its translation suggest that mime has limits. “How do you mime the intangible?” it states. Do the creators of the piece agree or disagree with this view? Or is this really only one of the thoughts of the depressed Mime himself?

Italian Mime Suicide has the advantage over Three Red Days in using an excellent live band (Arif Mirabdolbaghi, Justin Ruppel and Bruce Mackinnon). The company could have taken more advantage of this by generating more interaction between the band and the performers.

If the two plays are considered as two rough drafts, Three Red Days is one that really needs to be rethought, its action clarified and its performance better rehearsed. Italian Mime Suicide, has the potential to be an important work about mime and the threat to the art form in the modern world. To do this, the work needs to be expanded so we more fully understand the reasons for the Mime’s growing despair. At the same time, since mime transcends language, one might think, contrary to the view of the play, that mime would thrive in a multilingual world. In fact, the success of Italian Mime Suicide would seem to show that despite the despair and death of one mime, mime itself is very much alive.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: (from top) Miranda Calderon, Adam Paolozza, Rob Feetham and Viktor Lukawski; Miranda Calderon, Rob Feetham, Viktor Lukawski and Adam Paolozza. ©2016 John Gundy.

For tickets, visit www.badnewdays.com.

2016-10-10

Italian Mime Suicide / Three Red Days