Reviews 2016

✭✭✭✩✩

by Bahram Beyzaie, translated by Soheil Parsa & Peter Farbridge, directed by Soheil Parsa

Modern Times Stage Company, The Theatre Centre, Toronto

March 29-April 10, 2016

“I turn to right and left, in all the earth

I see no signs of justice, sense or worth” (Ferdowsi, Shahnameh)

Modern Times Stage Company has revived the Iranian play The Death of the King (sometimes translated as The Death of King Yazdgerd) by Bahram Bayzaie that it first staged in 1994. It is a fascinating poetic play about politics and power. The closest English equivalent to its heightened language and style is perhaps T.S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral (1935), which also looks at an event from its nation’s past to ask questions about the present. The physical production is beautifully managed but director Soheil Parsa has encouraged an over-emphatic style of acting that does not always present the work in the best light.

The play is based on a strange fact of history. King Yazdgerd III (reigned 623-651ad) was the last king of the Sassanian Empire before it was conquered by Muslim Arabs. The religion of the the Sassanids was Zoroastrianism. After the province of Pars fell to the Arabs, Yazdgerd fled to the city of Merv, where he and his few followers were defeated. He was founded stabbed in a flour mill and the miller was arrested, though some historians have doubted whether the miller was the real murderer

Bayzaie’s play opens with the presumed body of Yazdgerd already dead on the ground covered with a royal cloak and crown. A Commander (Carlos González-Vio) has already arrested the Miller (Ron Kennell) and has planned lingering deaths for him, his Wife (Jani Lauzon) and their mentally unhinged daughter (Bagareh Yaraghi). But the Miller and his Wife beg to explain what really happened. The three re-enact what happened, with each of the three at some point taking the part of the King. To the astonishment of the Commander and the Magu (Steven Bush), a Zoroastrian priest, the three claim that the King fled the battlefield and entered the mill disguised as a beggar. The three assumed that he must be a thief who had robbed the King of his cloak, crown and treasure. Eventually, the stranger convinced the three that he is their King but that he is so distraught over the state of the world that he wishes to commit suicide. Too cowardly to kill himself, he wants the Miller to do it for him. The Miller is now faced with a terrible dilemma – if he does kill the King, he is a murderer, but if he does not he is a traitor.

When the Miller refuses to act, the three claim that the King tried bribery, authority and finally shame, having sex with both the Girl and the Wife, to force the Miller to kill him. Twist follows twist in the tale the three tell until it becomes difficult for the Commander and for us to be certain what the truth really is. Doubt is even cast concerning the body of the King that has been lying in the foreground throughout the action. Since none of the religious or military officials have actually ever seen him, even they can’t be sure that the body is the King’s.

The intriguing part of Beyzaie’s play is how he uses impersonation as a means of critiquing social hierarchies and the fixity of identity. In telling the Commander and his followers what happened, all three peasants take turns acting the part of the King. At one point the Miller plays the King, the Wife plays the Miller and the Girl plays the Wife. When the family re-enacts the King’s attack on the Wife, the Wife plays the King and the Girl plays the Wife. This fluidity of role-playing implicitly critiques class difference not as inherent but as affectation. The role-playing within the play leads to the further irony that the military officials identified the King’s body not through recognition of his person but solely by his cloak and crown.

Bayzaie wrote the play in 1979 in the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution. Then the people ousted the Shah of Iran, the last of the Pahlavi dynasty, recalled the ayatollah and Iran became an authoritarian theocracy. The perceived rebellion of the Miller and his family against the last king of the Sassanian Dynasty serves as an historical analogue for the event.

What is unclear from Parsa’s production is the tone and point of view of the play towards the events it depicts. On the basis only of the production, the action could be viewed as tragic or as grimly comic. The play certainly begins as tragic with the threat that the Miller and his family will die horrible deaths for a crime they did not commit. The notion of a king who wanted to commit suicide is also not comic nor is the ending when all the arguments about who did what in the mill are made trivial by the approach of the invading enemy. On the other hand, while the tales of the Miller and his family seem true up to a point, as soon as they cast doubt on the identity of the corpse we wonder whether the family has decided to do so to exculpate themselves from the killing entirely. In this case, their wiliness in duping the officials would be comic, just as is the revelation that the officials really can’t prove who the corpse is. The arrival of the invaders would then be a blackly comic ending in which an entire society of corruption and lies is wiped out.

While there are a few lines that do seem intentionally funny, like the bumbling admission of the Private (Colin Doyle) that he does not really know what the King looks like, the vast majority of the dialogue, including the bickering between Miller and Wife, does not seem to be meant as comic. Yet, Parsa allows some cast members such over-emphatic acting that even the most serious parts of the play, including the sober introduction, become unintentionally funny.

Chief of the over-the-top performances is that of Jani Lauzon as the Wife. She begins the role with such vehemence and anger directed at the Commander that she has nowhere to go and remains at this overwrought pitch throughout the show, except, strangely enough, when she takes on the role of the King. Lauzon’s responses are so exaggerated they often lead one to think they are meant to be humorous.

In between these extremes lie the rest of the cast. As the Girl, Bagareh Yaraghi begins on too frantic a note, but is able to climb down from that level to use a well-modulated voice for the rest of the play. The scenes in which she plays the King are especially strong and she lends mystery to the Girl’s obsession that the corpse is really that of her father.

As the Miller, Ron Kennell tends to be too frenzied, but he is excellent at differentiating the Miller as narrator from the Miller as himself. As a narrator Kennell is mesmerizing and seems to be recounting the events he witnessed as if in a trance. All that one might wish is some hint of a distinction between when the Miller as narrator is telling the truth and when he begins to lie.

Steven Bush is not very quick off the mark as the aged Magu and certainly does not exude the threatening authority that González-Vio and Baek do. The Private played by Colin Doyle is the only purely comic character in the play, but Doyle’s timing and delivery need to be tighter to be more effective.

The physical production is beautiful. Trevor Schwellnus had designed a raked circle where all the narration takes place, a circle that is also a suitably abstract symbol of a mill. The expert changes of lighting instantly tell us when the Miller’s family are re-enacting events or being themselves. Thomas Ryder Payne’s music and sound design add immeasurably to giving the action a sense of place. As usual, Parsa’s physical, quasi-ritualistic direction is a pleasure in itself.

Modern Times Stage Company has championed Iranian theatre, particularly the works of Beyzaie, from its foundation in 1989. As in his Aurash seen here in 2010, he is clearly an inventive writer and we owe Modern Times thanks for reviving The Death of the King for all those who did not have the chance to see it before. With a more even cast and a better communication of the play’s tone, the show would reach the same high level as so many other of Modern Times’s productions. As it is, anyone even mildly curious about drama from the lands between Europe and Asia should make a point of seeing this play simply to take advantage of the luxury of Modern Times has given us of being able to experience a different form of theatre. Beyzaie’s play provides much food for thought and makes one long to see more of his works.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

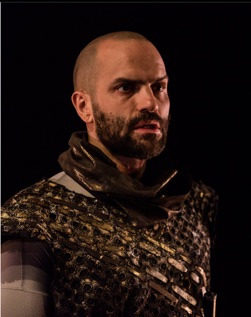

Photos: (from top) Bahareh Yaraghi, Ron Kennell and Jani Lauzon; Ron Kennell (foreground), Sean Baek, Carlos Gonázlez-Vio and Colin Doyle; Carlos Gonázlez-Vio. ©2016 Jeremy Mimnagh.

For tickets, visit http://theatrecentre.org.

2016-03-30

The Death of the King