Reviews 2016

✭✭✭✩✩

written by Daniele Finzi Pasca & Julie Hamelin Finzi, directed by Daniele Finzi Pasca

• Cirque du Soleil, Grand Chapiteau, Port Lands, Toronto

July 28-October 16, 2016;

☛ Touring North America until December 15, 2019 – see below

‘O’ Minor

Cirque du Soleil’s Kurios set the bar so high in 2014 that any Grand Chapiteau spectacle thereafter would have to be really special to equal it. Cirque du Soleil’s new show Luzia that premiered in Montreal in April this year does not reach the same heights. Rather, it feels like a throwback to earlier CdS shows like Amaluna of 2012 or OVO of 2009. Instead of presenting a vision of an alternate future, Luzia once again gives us a vision of animated nature, this time with Mexico as its prime influence. Developing new technology has always been part of Cirque du Soleil creations, but in Luzia there’s an unfortunate emphasis on technology for its own sake that tends to obscure the human achievements it ought to enhance.

In the midst of this attractive garden is a two-part treadmill that runs the full diameter of the circular stage. Once the garden is removed, this treadmill becomes a key element of the first act of hoop diving done by a troupe from Canada, the US and France. Hoop diving, in which acrobats leap and somersault through a series of small vertical hoops, has been a feature of previous CdS shows like Dralion (1999) and non-CdS shows like Traces (2006) by Les 7 Doigts de la Main. The excitement of this act comes from watching performers run up to set of hoops and hurl themselves head- or feet-first through them. The difference here is that the treadmill does the forward propulsion for the acrobat and this severely dampens the thrill of the act. The treadmill simply conveys the acrobat up to the hoops and he or she jumps through, often with the help of others.

The circular stage consists of two revolves – an outer ring and an inner platter – that can turn together in sync or at different speeds. The revolves are used for almost all the acts so that everyone in the audience will get a front on view of the action at sometime during the act. The downside is that director Daniele Finzi Pasca sometimes uses the outer ring unhelpfully.

For the Act 2 opener featuring masts and poles, Finzi Pasca places female acrobats on three poles on the outer ring and two male acrobats on the Chinese poles at the centre of the platter. Four acts occurring simultaneously is already too difficult to take in, but to make things worse, Finzi Pasca has the outer ring revolve, so that not only are the three outer pole artists moving while they do their routines but they periodically obscure the routine of the inner pole artists. Act 1 saw something similar when American Cyr wheel artists perform at the centre of the stage while fake Monterrey pine trees on the revolving outer ring needlessly pass by. One point of having advanced technology is knowing when not to use it.

The most blatant use of technology for its own sake is the rain machine that gives Luzia its name. The name is a conflation of two Spanish words – “luz” meaning “light” and “lluvia” meaning “rain”. Cirque du Soleil already has its renowned water-themed show ‘O’ that has been running at a permanent site in Las Vegas since 1998. Technologically, Luzia is an attempt to bring some of aspects of ‘O’ to a touring show. When it is first used in Act 1, the rain machine functions just like any ordinary such machine in a theatre and douses the performers underneath it with water. The Cyr wheel performers even continue their routine while it is raining. Although the stage is perforated with almost 95,000 holes to allow the instant drainage of the stage into a basin below, the stage still needs to be dry for the following acts. For that reason there is an overlong interlude with the show’s Clown (engaging Dutchman Eric Fool Koller [sic]), who tries to set up a rivalry between the left and right half of the audience in a form group volleyball to occupy the time while the crew mop the stage.

Later in Act 1 the Clown, whose water bottle has been empty since the start of the show, tries to get water from the rain machine. Here we discover that unlike any ordinary rain machine, this one has nozzles that can function independently. Thus, it can send a trickle from the far right or the far left to force the Clown to rush from one side of the stage to the other. The climax of this scene is the revelation of the rain machine as a major technological marvel.

From a torrent of rain released from the long bar of the machine high above the stage, patterns gradually emerge in the downpour made by gaps in the raindrops. They begin with simple animal forms and then become ever more complicated, eventually imitating the intricate Mexican art of cut paper patterns known as papel picado. This is an extraordinarily beautiful effect and with the light illuminating the rain sums up the the combination in the show’s title Luzia. The main problem with this effect is that it has absolutely nothing to do with human beings in performance. The audience may applaud but they are not applauding a person but the gigantic equivalent of an ink-jet printer that uses water instead of ink.

The unpleasant question Luzia forces us to ask after seeing everything from little robots to this huge “graphical water display screen”, as it is called, is whether Cirque du Soleil will eventually allow displays of feats of technology to displace feats of live human performance. The technology of permanent shows like floating double stages of Kà and the instantly appearing and disappearing pool of ‘O’ helps to give circus performers new ways to stage familiar acts and even to invent new acts. Here in Luzia when the audience applauded the computer-operated rain machine, it felt like a boundary had been crossed where an elaborate special effect was receiving as much acclaim as a human performer.

Other than this strange side to the show, Luzia falls into the familiar pattern of a non-narrative CdS show. The Clown is the visitor to a strange world that just happens to be dreamlike version of Mexico. None of the acts in the show are surprises that we haven’t seen before, like the breath-taking Wheel of Death in Koozå (2007) or the stick-balancing routine in Amaluna (2012). Rather many are simply variations on the familiar.

Perhaps the most beautiful of all the acts is Americans Angelica Bongiovonni and Rachel Salzman on Cyr wheels. This is an apparatus more often used by men than women, but these women make it fully their own. Costume designer Giovanna Buzzi has clad the two in yellow flowered dresses that swirl upward exactly within the circumference of the wheel. The women not only dance inside wheels while twirling them but also perform the more typical male stunts of cartwheels and coins. The women are so entrancing on their wheels that one has to remember to look up at American Emily Tucker on the dance trapeze above them.

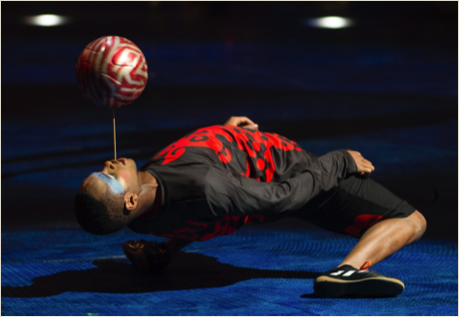

As proof that some of the least technological acts can be the most exciting is the football dance routine of Abou Troaré from Guinea and Laura Biondo from Italy. The tricks they can do with just a soccer ball are simply amazing like tumbling or even break-dancing while holding the ball with one foot. Because it requires no special apparatus or costume, this is the act that will likely most appeal to young people.

Other than the scene where the curtain of rain becomes a graphical water display screen, only one act makes any effective use of water. That, oddly enough, comes about in the course of a fantastic aerials straps act by Canadian Benjamin Courtenay. Only for Courtenay’s act is the water basin below the stage opened up. Courtenay does the typical strength displays of holds, twists, rolls and poses, but he is also frequently dunked into and pulled up from the water basin, making patterns of spray as he rises. At the conclusion of his act he does a spectacular head downward drop until his long hair is soaked in the water. This he follows with a series of one-armed swings, his hair dipping in each time, so that his circular movements are augmented with circles of following water drops.

The most bizarre act of the evening is the contortion of 21-year-old Russian Aleksei Goloborodko. Seldom has Cirque du Soleil so highlighted the work of a male contortionist. Goloborodko is already so famous in Russian that he been acclaimed “the most flexible human on the planet”. When he first appears on his platform, you merely see what seems to be a pile of clothing. Amazingly, the pile unwinds itself to reveal that it was really a person compressed to its smallest possible size. Goloborodko is a backbender so that the majority of his moves involve chest stands and variations of the headseat where the buttocks rest, incredibly, on top of the head. Many of his moves, such as draping parts of himself over other parts as if he were completely boneless, are ones that I’ve not seen even female contortionists perform and are so grotesque they are not especially pleasant to look at.

The show concludes with a Russian swing act. Unlike a normal swing, a Russian swing has a platform that is rotated 90° in relation to the overhead bar. With two Russian swings one performer pumps the swing and another makes acrobatic leaps from one swing to the other. It’s rather odd that Finza Pasca would choose this kind of act to end the show since Russian swings have featured in at least four previous Cirque du Soleil shows including Saltimbanco (1992), ‘O’ (1998) and Varekai (2002). The team from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus have lots of energy but their routine is far from thrilling. In the best Russian swing acts, the flier will leap from one moving swing to another moving swing. Here those in charge of the landing swing stop it to make the flier’s landing easier. Needless to say, this act does not end the show on the high note one would expect.

Cirque du Soleil now produces so many shows worldwide that it is impossible for them all to be equally good. While I could easily see Kurios a third time, I grew tired of Luzia by intermission. Luzia may be lovely to look at but its pacing is languid partly because every use of the rain machine requires such a lengthy clean up, partly because Finzi Pasca allows the striking of one apparatus and the setting up of the next to be so slow and deliberate. He may think this helps to create the effect of a dream, but it also allows the energy from one act to dissipate before the next begins.

Most people will probably remember Luzia because of its programmable rain curtain. If so, that will be very sad because it is absolutely the wrong reason to attend Cirque du Soleil. Try instead to think of the women spinning on Cyr wheels, the soccer ball whiz kids, the high speed juggler and the aerial straps artist, arcs of water retracing his every move.

©Christopher Hoile

Running time: 2 hours, 25 minutes, including intermission.

Tour stops after Toronto, ON:

• San Jose Arena, San Jose, CA

February 9-March 5, 2017;

• King County’s Marymoor Park, Seattle, WA

March 31-May 21, 2017;

• Pepsi Center - Prius West Lot, Denver, CO

June 1-25, 2017;

• United Center (Parking Lot K), Chicago, IL

July 21-September 3, 2017;

• Atlantic Station, Atlanta, GA

September 14-November 19, 2017;

• Dodger Stadium, Los Angeles, CA

December 8, 2017-February 11, 2018;

• PC Fair & Event Canter, Costa Mesa, CA

February 21-March 18, 2018;

• Tysons II, Washington, DC

April 13-May 13, 2018;

• Suffolk Downs, Boston, MA

June 27-July 29, 2018;

• Gran Carpa Soeil en Av, López Mateos, Guadalajara, MEX

August 30-September 16, 2018;

• Gran Carpa Soleil en Valle Oriente, Monterrey, MEX

October 4-21, 2018;

• Gran Carpa Soleil en Santa Fe, Mexico City, MEX

November 8-December 23, 2018;

• Sam Houston Race Track, Houston, TX

January 10-February 24, 2019;

• Under the Big Top The Florida Mall, Orlando, FL

March 7-31, 2019;

• The Big Top next to Citi Field, New York, NY

May 3-26, 2019;

• On Market Street, Hartford, CT

June 19-July 21, 2019;

• Stampede Park, Calgary, AB

August 16-September 22, 2019;

• Concord Pacific Place, Vancouver, BC

October 3-December 15, 2019

– then to Europe.

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Shelli Epstein as the Running Woman; Robot; Angelica Bongiovonni (Cyr wheel), Shelli Epstein, Emily Tucker, Rachel Salzman (Cyr wheel); Abou Troaré (soccer ball); Benjamin Courtenay (aerial straps). ©2016 Sébastien St-Jean.

For tickets, visit www.cirquedusoleil.com/luzia.

2016-07-30

Luzia