Reviews 2016

✭✭✭✩✩

by Thornton Wilder, directed by Molly Smith

Shaw Festival, Royal George Theatre, Toronto

May 12-October 15, 2016

Stage Manager: “There’s some scenery for those who think they have to have scenery”

The Shaw Festival has already staged two of Thornton Wilder’s lesser known plays – The Skin of Our Teeth in 1984 and The Matchmaker in 2000 – so it is about time it got around to his best known work and one of the undisputed classics of American drama, Our Town of 1938. The play is directed by American Molly Smith, who, strangely enough, knows that the play was revolutionary for its minimalist aesthetics yet chooses not to follow them. Besides a number of odd directorial and design choices the central role of the Stage Manger is miscast making the production feel like a missed opportunity.

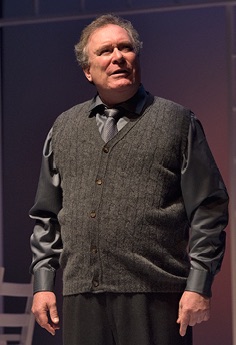

Wilder’s play follows the course or everyday life in the town of Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire, population 2642, in the years 1901, 1904 and 1913. Our guide is a narrator called the Stage Manager (Benedict Campbell), who focusses his story on the lives of two neighbouring families, the Webbs and the Gibbses. In three acts we see the childhood of George Gibbs (Charlie Gallant) and Emily Webb (Kate Besworth), their falling in love and marriage and last Emily’s funeral after her death in childbirth. The point of the play is to document the lives of ordinary people of a certain time and place because history too often records only the lives of famous people and rulers.

The aesthetic of the play is rigorously minimalist as spelled out in its opening stage directions: “No curtain. No scenery. The audience, arriving, sees an empty stage in half-light”. Later, two trellises are rolled in (here flown in) when the Stage Manager says making fun of stage conventions, “There's some scenery for those who think they have to have scenery”. Other than this, all the props are common objects or are mimed.

The paradox of Smith’s production is that she seems to be one of “those who think they have to have scenery”. When we enter the stage is bare and in half-light, albeit with a ghost light downstage centre, which should not be there when the stage is lit or especially when an audience is present. Smith is using it to symbolize the fact that most of the main characters we meet are already dead.

The other odd detail is that the entire stage of the Royal George Theatre has been covered with bright white wooden floor boards with narrow gaps between them. We soon discover that there are lights under these gaps to shine through for various effects. In a move not in the text, Smith has the Stage Manager gesture and a plain drop flies down to cover the bare back wall of the stage so it can reflect Kimberley Purtell’s varied lighting effects. What we have to ask Smith is what part of “no scenery” and “empty stage” does she not understand? She has had Ken MacDonald cover the stage with a technologically enhanced floor and cover the back wall, thus creating a set for a play that is meant not to have any. MacDonald has also designed bright white furniture to look like ordinary furniture to match the floor. Worse, instead of the ordinary step adders meant to be used for the facing windows of George and Emily, MacDonald has designed two rolling towers with a ladder on one side but with platform that looks less like the window sill it is meant to represent than does the top step of a regular step ladder.

In another peculiar decision, Smith has had William Schmuck colour-code the characters’ costumes. Now we might be able to understand why the Milkman (Jeff Irving) wears all white or why the Paper Boy (Billy Lake) wears a colour that looks like yellowed paper. Simon Stimson (Peter Millard), the town drunk, wears all burgundy and Mrs. Webb (Jenny L. Wright), who strings green beans wears all green. That doesn’t explain, however, why George wears all burnt orange and Emily an icy blue, or why all the men at George and Emily’s wedding wear black shirts, which was certainly not the custom at the time.

Molly Smith’s worst choice is to have James Smith construct a detailed soundtrack to accompany the actors’ miming. Thus we hear house and oven doors open and shut, sink noises, baseballs caught, bottles rattling, horses hooves and neighing all of which is unnecessary and disrespects the actors’ artistry in mime. Molly Smith allows James Smith’s music to accompany and often cover up the words of key passages and, disregarding Wilder’s minimalism entirely, she has a snow machine blanket the Act 3 cemetery in fake snow that Wilder would rather have us imagine.

An aspect of this production quite unusual at the Shaw Festival is that the characters do not have uniform accents. The inhabitants of Grover’s Corners grow up, live and die there, yet Kate Besworth as Emily and Billy Lake as the Paperboy seem to have come from New York City and Emily’s accent does not match those of her parents or of George. Some like Benedict Campbell put on a successful New England accent, but most others don’t bother.

Among the many fine performances several stand out. The best all-round performance comes from Charlie Gallant as George Gibbs. He shows the greatest changes in character at the three times of childhood, adolescence and maturity. He makes two moments particularly memorable. One the utter shame that comes over George when father chides him for not doing his share of the housework. The other is awkwardness of his conversation with his future father-in-law, Mr. Webb (Patrick McManus).

Ideally, Kate Besworth’s Emily should be equal to George. Unfortunately, Besworth allows the deliberateness of her accent to interfere with the naturalness of her delivery. Her scene of falling in love with George at the soda fountain is her best, but her more important scene, that of realizing the pain of reliving an ordinary day, seems rushed without enough expression of frustration and despair.

Of the four parents, Catherine McGregor’s Mrs. Gibbs and Patrick McManus’s Mr. Webb provide a stronger feeling of their characters’ inner life than do Patrick Galligan as Dr. Gibbs or Jenny L. Wright as Mrs. Webb. David Schurmann makes his two roles quite distinct. One is comically pedantic Professor Willard, who gives a lecture about Grover’s Corners. The other is the grimly impassive undertaker Joe Stoddard. Peter Millard makes a big impression the the small role of Simon Stimson, the church organist and choir leader as well as the town drunk. This is the only perpetually unhappy character in the play and the only character the Stage Manager suggests would have been better off living in a big city. We can’t know what the Stage Manager is implying, but Millard suggests that drink is the only way Stimson has of calming some perceived vice that is consuming him from within.

Paring his staging down to the most minimal requirements is the structural parallel of Wilder’s paring down his story of everyday life to a glimpse in three separate years of two youngsters from two families in one unremarkable small town. To go against Wilder’s Spartan minimalism is to work against the impact of the story. Smith’s attempt to make the play prettier and more spectacular has just this effect. This leaves Soulpepper’s rigorously unsentimental production of 2006 likely the best professional Our Town presented in Ontario in the last 30 years. The current Shaw Festival cast is very strong and with different direction and design could well have come close to equalling Soulpepper’s achievement.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: (from top) Kate Besworth, Charlie Gallant, Benedict Campbell and ensemble; Charlie Gallant and Kate Besworth (on ladders) and ensemble; Benedict Campbell as the Stage Manager. ©2016 David Cooper.

For tickets, visit www.shawfest.com.

2016-08-07

Our Town