Reviews 2017

✭✭✭✭✩

by Adam Lazarus, directed by Ann-Marie Kerr

The Theatre Centre & QuipTake with Pandemic Theatre, The Theatre Centre, Toronto

November 9-19, 2017;

Rossy Pavilion, National Arts Centre, Ottawa

February 9-10, 2018

“I’ve done a lot of bad things”

Adam Lazarus’ controversial solo play Daughter was a massive hit at SummerWorks last year. Now The Theatre Centre and QuipTake with Pandemic Theatre have remounted it and given more people a chance to see it and judge the work for themselves. It’s a deeply disturbing piece, all the more so because Lazarus is such a charming, engaging performer. But the deliberate strategy of the play co-created by Lazarus, Anne-Marie Kerr, Melisssa D’Agostino and Jiv Parasram is to lure the audience into the mind of Lazarus’ character where he harasses it with increasingly unsavoury stories and images. By the end you may well fell unclean and ashamed. It’s not an enjoyable show, but its process and the mindset it exposes could not be more topical and are vitally important to recognize.

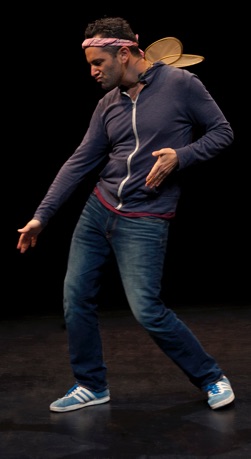

The show begins innocently enough with Lazarus appearing on a bare stage wearing a headband, butterfly wings and rolling a hula hoop while an iPhone on a stool plays pop music through a speaker. He says what we’ve been listening to is from his 6-year-old daughter’s playlist. He asks if we want to see a dance that his 6-year-old created just for him and then proceeds to perform a fairly sexualized dance with lots of chest shaking and pelvic thrusting. Everyone laughs at the disparity between the conventional notion of childhood innocence and the obvious raunchiness of the dance. But no, it was all a joke, Lazarus tells us when the laughter dies down. He then says he’ll show us the “real” dance that his daughter created for him. On the iPhone he punches in the boppy song “Everything Is AWESOME!!!” from The LEGO Movie (2014) and does a much simpler dance with lots of simple jumping up and down and repeated arm movements – something we can more easily imagine a six-year-old teaching her father.

Though we don’t know it at this point, Lazarus and the show’s co-creators have already introduced us to the play’s theme. His “joke” of a dance reveals his character’s central problem – an inability to think of females, even his own daughter, in other than sexual terms. Yet, we have no time to think deeply about this because Lazarus immediately draws us into the story of his daughter’s difficult birth.

He describes the difficulty he had when his daughter was little and was always getting out of bed at night. One night after her sixth or seventh time waking him up, he manhandled her, forcefully pushed her down into her bed and told her not to get up again that night. He then asks the audience outright whether they approve or disapprove of what he did, because he is still not sure it was right. The audience is divided in its opinion.

It’s hard initially to judge the nature of the character Lazarus is playing (or is it Lazarus himself?) because we know nothing about him. But Lazarus’ flashbacks to his own life starting at age six and moving forward tell us the story and reveal a pattern. Lazarus is sure that the audience all remembers the first time it drank pee. He does because he had to drink some to prove the pee was lemonade in order to make a girl drink it as part of his revenge on her. Fortunately, she saw through the scheme. He also recalls being at school, pulling out his penis and threatening to pee on girls, assuming that this is not something out of the ordinary.

When he moves forward to his teenaged years he tells of amassing a huge amount of porn downloaded at dial-up speed from the internet, the delay of finally seeing breasts appear being itself a kind of pleasure. He enumerates all the different types of porn he collected including orgies and gang bangs, but, as if to show that even he had his limits, he tells us he discovered there were types of porn he could never enjoy, namely namely bestiality, scat and fisting. That didn’t prevent him, however, from keeping examples of these latter types, supposedly to remind himself of what he was not into. As if hearing about this were not enough, Lazarus then acts out one of the videos he saved, a “classic” he says that we must know, about a woman having sex with a horse. This he demonstrates in exactly the same position he had previously used to imitate his wife moaning in pain in her marathon labour session.

If we have paid attention, Lazarus has said he is “not into” three types of porn, not that he finds them objectionable. His acting out the horse rape scene shows that he even thinks these types may be amusing.

Lazarus then describes going to Japan, where to his delight he discovers that white men receive deferential treatment from Japanese women over Japanese men. Having lived in Japan myself for two years, I can say that it is easy early on to judge male gaijin (foreigners) based on their view of Japanese women’s traditional behaviour. Those who continued to find female deference enjoyable you wanted to avoid. Those who found it demeaning to women were more enlightened.

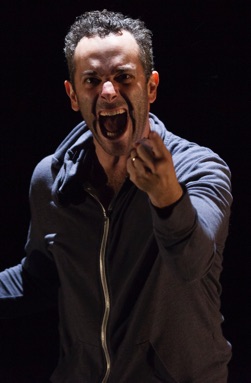

After a further unsettling story he suddenly launches into an invective against women, including his daughter. Sensing our objection, he says, “that’s what this type of show is for, isn’t it? To say what we really think about things?”

If we feel our blood rising in anger at the end of the show it is because the show has been carefully, almost insidiously, structured as a premeditated sexual assault. The male predator is charming, even a bit goofy. he portrays himself as a family man and wins us to his side with the tale of his wife’s difficult birth. Having created a bond of sympathy with him, he reveals more and more of his secrets checking all the time that we can understand that that is how someone of his age at the time would act. Each of our assents, even if in silence, even as part of an audience, makes us complicit in his continuing to test our tolerance of his behaviour. Having established, from his point of view, that we and he think alike, it is a small step for him to think we will approve of his aggression, even though it is only verbal, in attacking women.

One reason why we continue listing to Lazarus’s increasingly disturbing self-revelations is because Lazarus and his collaborators are knowingly playing with the form of the confessional solo show. The mere listing of three co-creators for the show should tip us off that the show cannot be strictly autobiographical. An audience will accept all kinds of unpleasant revelations if the show is framed in a personal confessional mode. Here, however, the appearance of personal revelations is to make us feel complicit in an objectionable ideology. In fact, he is using the audience’s role as passive listeners as unfair proof of our consent.

The show works so well because Adam Lazarus has the amazing ability to make what he says appear improvised. His demeanour is so non-threatening and his delivery so apparently off-the-cuff that we easily forget that the show is a show with a predetermined trajectory.

Yet, likeable as Lazarus makes his character seem, that character is the perfect embodiment of the toxic masculinity that has been so much in the news of late. That fact and the creators’ deliberate abuse of the audience’s passivity make Daughter a show that gives chilling insight into a form of maleness that derives pleasure from dominance and power, not compassion, and treats all others who disagree as weak and worthy only of degradation. Daughter is an important and powerful play, but many should be warned that it contains images and phrases that they may wish they could later unsee and unhear.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Adam Lazarus; Adam Lazarus; Adam Lazarus. ©2017 John Lauener.

For tickets, visit http://theatrecentre.org.

2017-11-10

Daughter