Reviews 2017

✭✭✭✩✩

music by David Shire, lyrics by Richard Maltby, Jr., book by Craig Lucas, directed by Adrian Noble

Garth Drabinsky, Elgin Theatre, Toronto

March 23-April 9, 2017

Sousatzka: “The music is in you”

Now enjoying its world premiere the musical Sousatzka is former Livent impresario Garth Drabinsky’s bid to re-enter the world of producing Broadway musicals. The musical is well cast, well acted and well sung but it is overproduced and uninvolving. It is the story of a piano teacher successfully guiding a child prodigy to success, but why anyone thought it would be a good subject for a musical is a mystery. Teacher and pupil may sometimes disagree, but that hardly constitutes dramatic conflict.

Instead, Craig Lucas’s book tries to locate conflict in the separate pasts of the two protagonists which only tends to isolate them even more. The result is a musical where the main figures come to embody Big Themes but never become real characters. Composer David Shire and lyricist Richard Maltby, Jr., have written song after song about overcoming adversity when by the time of the action, the worst adversity the characters have faced is already overcome.

The musical claims to be based on “the original novel Madame Sousatzka by Bernice Rubens”. This is a bit of a canard. Rubens’s original 1962 novel was about the Russian émigré piano teacher Madame Sousatzka teaching the Jewish, British-born child prodigy Marcus Crominski. When the novel was made into a film in 1988, screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala changed Madame Sousatzka to a Russian-American immigrant to suit actor Shirley MacLaine and made Marcus Crominski into Manek Sen, the son of a Bengali immigrant. According to Craig Lucas, influenced by Garth Drabinsky’s desire to bring “together onstage the world of the Jewish diaspora from Eastern Europe and the struggles of the South African anti-Apartheid activists in exile”, Lucas has changed the story even more. Now Madame Sousatzka is a Polish Holocaust survivor and Marcus Crominski has become Themba Khenketha, the son of an imprisoned anti-apartheid leader in South Africa. What had originally been a delicate story about the split duties of a young boy to his mother and his teacher has now been overblown into a meeting of two survivors of nationalized racist regimes.

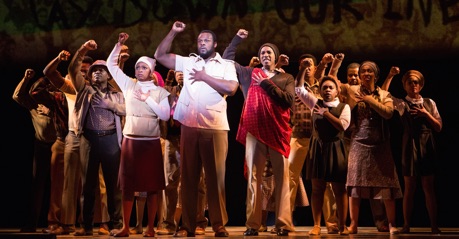

The action of the musical begins in South Africa where we see the protest where Themba’s father is arrested, where he is tried and imprisoned for life on Robben Island. In flashbacks through the musical we see how Themba’s aunt warns Themba’s mother to flee South Africa with Themba, how they are received by the ex-pat South African community in London and how Themba’s aunt arranges for Themba to study with Madame Sousatzka, “the greatest piano teacher in London”.

After Themba meets Madame Sousatzka and begins his studies, Lucas begins to give Sousatzka flashbacks of her own. We learn that Sousatzka’s friend the Countess, who lives with her and Sousatzka’s odd collection of exiles, helped Sousatzka escape Poland after all of Sousatzka’s relatives were sent to their deaths. Thus, as is heavily underlined, both pupil and teacher are immigrants who have escaped fascist regimes. The problem with all of this background, no matter how well depicted, is that it has absolutely nothing to do with the main plot, i.e. Sousatzka’s nurturing of Themba to success. In the main song of the show, Sousatzka tells Themba “You have the music in you”. All he needs to do is allow the music to play itself. Thus, according to this formalist view, what background he brings to the music doesn’t matter.

Of course, the difficulty about a story where a gifted pupil continually improves while practicing the piano is that all the hard work he does is not inherently interesting. Therefore, besides filling out the show with the excursions into the backgrounds of pupil and teachers, Lucas also lards it with vignettes of all the minor characters. Thus the gay osteopath who lives in Sousatzka’s building gets a song, so does the prostitute who lives there, so does the music impresario who is the prostitute’s regular client, and so does even the the impresario’s wife. Lucas thinks we should get some glimpse into Themba’s private life outside of piano practice, and so gives him a ballerina girlfriend who also happens to like visiting punk rock clubs. Since this, like the show’s already too numerous subplots goes nowhere, it ought to have been omitted.

Meanwhile, just when Themba is about to make his first public appearance, Lucas decides he should be haunted by memories of his father and question his gift for pianism as inferior to his father’s sacrifice for politics. This leads to Themba’s father singing in 1982 about South Africa as a “Rainbow Nation”. That phrase was coined by Bishop Desmond Tutu in 1994 after South Africa’s first fully democratic elections. No matter how uplifting the song, it seems rather unfair to ascribe Tutu’s important phrase to a fictional character twelve years earlier.

The second act revolves around Themba’s first major concert. The only action is waiting for the concert date, that just happens to be at Christmas, to arrive. To fill the space, Lucas gives all the major characters yet another would-be show-stopping song including the worst song of the evening, the Countess’s totally needless Christmas song “Ring One Bell” which makes the remarkable observation that “Christmas comes round every year”.

The score for the musical covers an extremely wide range. Not only do we have traditional South African music, Eastern European waltzes, jazz, quotations from classical music and disco, but Shire and Maltby have written a series of earnest, classically tinged power ballads all on the uplifting theme of hope conquering doubt. Unsurprisingly, all these major solos tend to sound pretty much the same. The show should drop the visit to the punk rock club since Shire’s notion of punk seems to be disco, its polar opposite.

The most ingenious sequence in the whole show is the scene when the audience of Themba’s big concert sits facing front and sings about how they feel Themba’s performance is going to the tune of the Bach keyboard concerto that Themba is playing. Otherwise, the most moving music in the show appears in the scenes set among the South Africans. This is not surprise because Lebo M, who wrote the African music for The Lion King, also wrote the African music and lyrics in Sousatzka.

The performances under Adrian Noble’s direction are faultless. Victoria Clark has a near-operatic voice and sings with great nuance and feeling. As an actor she is perfect at conveying both the rigour and the eccentricity of Sousatzka. To see her perform is a pleasure in itself. Newcomer Jordan Barrow is a major find as Themba. He is an intense, realistic actor, he sings with passion and he can convincingly play well-known classical pieces on the piano. It’s hard to understand the ups and downs of Themba’s mother Xholiswa as played by Montego Glover. She’s pleased that Themba gets to study with London’s greatest piano teacher, yet she doesn’t personally like Sousatzka and is on the point of taking him away. Glover’s voice tends to be drowned out on ensembles but she does shine in her main solo number “Song of the Child”.

Ryan Allen, who plays Themba’s father Jabulani, also has an operatic voice and uses it to impressive effect in all his numbers. Judy Kaye, who was such a delight when last here as Mrs. Lovett in Sweeney Todd, is given little to do as the Countess except make veiled remarks about Sousatzka’s past.

Costume designer Paul Tazewell lets his imagination go wild, especially in the scene of Themba’s appearance at a private salon where the guests’ costumes are so outré they contradict the show’s general look of realism. Elements of Anthony Ward’s computerized sets slide in and out, up and down, as if all part of some huge, clockwork machine. On the one hand the precision of the multiple scene changes is impressive. On the other, the mechanical nature of the changes tends to emphasize the mechanical nature of the entire show which seems entirely geared to hit as many audience demographics as possible.

In its emphasis on grandiose production values over a focus on character development, Sousatzka picks up exactly where Livent left off in 1998 with such large-scale musicals as Showboat in 1993 and Ragtime in 1996 which have since proved much more successful in smaller-scale formats. Drabinsky may have lined up a list of famous artists in their fields for the musical, but Sousatzka completely lacks the invention, freshness and verve of such recent musicals as Matilda the Musical (2010), Once (2011) or Canada’s own Come From Away (2015). Sousatzka claims that it it is Broadway-bound, but Broadway has moved away from the earnest, overproduced stodginess that could win it fans if only as a prestige production. No matter how well performed and decked out, a musical without conflict or characters to care about will only will stimulate the snooze response rather than the intellect or emotions. At the very end, the show which had been skimming the surface of oversentimentality for almost three hours, finally gives up the effort and plunges into it headlong.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Jordan Barrow and Victoria Clark; Montego Glover, Ryan Allen and company; Victoria Clark, Judy Kaye and company. ©2017 Cylla von Tiedemann.

For tickets, visit http://sousatzkamusical.com.

2017-03-24

Sousatzka