Reviews 2018

✭✭✭✩✩

by William Shakespeare, directed by Graham Abbey

Groundling Theatre Company, Harbourfront Centre Theatre, Toronto

January 12-28, 2018

Fool: “Have more than thou showest,

Speak less than thou knowest” (I, 4)

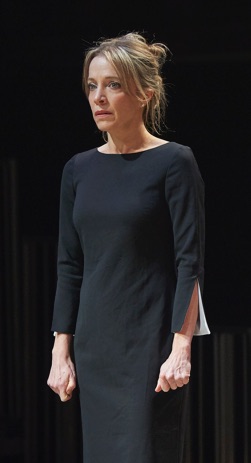

The the first thing to know about Groundling Theatre’s production entitled Lear is that it is not the 1971 play of that title by Edward Bond, who radically rewrote Shakespeare’s play as a social critique of what he felt was an even more brutal age. Instead, Groundling is presenting Shakespeare’s original play with a significant difference. A female actor, Seana McKenna, plays the title role. All words pertaining to Lear’s gender have been changed so that McKenna is in fact playing Queen Lear. Glenda Jackson played a Queen Lear in London in 2016 as did Diane D’Aquila in Toronto in 2017, so Groundling is not exactly breaking new ground. Nevertheless, for those who saw neither of those productions, the Groundling production will convince any doubters that the iconic role suits a woman just as well as a man.

The Groundling production also demonstrates, in case anyone did not know it, that Lear is the most difficult role ever written for an older actor. To be effective an actor cannot merely fall back on familiar techniques but must find new means of expression to suit the new world of utter deprivation and madness that Lear encounters. This, unfortunately, is exactly what McKenna does not do except for a few moments where she allows us a glimpse of rawer emotion than she has hitherto ever shown on stage.

In Shakespeare’s text Lear gives his age as “Fourscore and upward, not an hour more or less”. In this production, McKenna’s Lear says she is “threescore”. Therein lies one of many difficulties that beset McKenna’s Lear. At the start of the play and indeed even through the storm scene of Act 3, scene 2, and beyond, McKenna’s Lear is far too hale and hearty. Though she calls herself “old” as do her daughters, McKenna’s Lear is far too vigorous.

When she claims, “’tis our fast intent / To shake all cares and business from our age; / Conferring them on younger strengths, while we / Unburthen’d crawl toward death”, she starts the play on a completely false note. McKenna gives Lear so much command and authority it doesn’t make any sense that she would want to give up the power she so clearly enjoys wielding. No matter what the text says, McKenna shows Lear in no way enfeebled in mind or body or in any way haunted by the thought of approaching death.

The effectiveness of the production never fully recovers when its premise is so thoroughly undermined. Yet, one good insight director Graham Abbey has is to relate Lear’s anger at Cordelia’s unexpected response to Leontes’ sudden fit of jealousy in The Winter’s Tale written four year later. Abbey has the three portions the daughters are to receive all set out on Lear’s desk so that the “love test”, as it is called, is clearly seen by Lear as a mere formality. When Cordelia refuses to play along, Lear’s anger mounts so high so rapidly that it is indeed quite like the fit that overtakes Leontes. The difference is that Lear’s later rejection by Goneril and then by Regan cause secondary fits that show us a mind losing all sense of stability.

Other than playing Lear as not at all infirm, McKenna’s greatest difficulty with the role is the same as that seen in the Lear of Brian Bedford at Stratford in 2007 and in Christopher Plummer there in 2002. All three wished their Lears to go mad in the most attractive manner possible, which, needless to say, is completely contrary to the descent into the abyss that Shakespeare depicts.

People when mad lose any irony along with control. They have no intellectual distance from what they perceive since what they perceive, no matter how outlandish, seems real. As an actor McKenna has always been a master of the ironic tone which makes her so superb in plays where her character is in complete control or in Restoration and 18th-century comedy characterized by wit. The problem here is that McKenna holds on to her ironic tone of voice far too long into Lear’s mad scenes with the result that her Lear seems to be merely eccentric like Giraudoux’s Madwoman of Chaillot that she played last year. Rarely does she give us any hint of the kind of soul-searing madness that so dispirits Lear’s observers such as Gloucester and Edgar. Only once in Lear’s mad scenes on the heath does Mckenna give a glimpse that she is capable of something beyond her familiar irony. In Lear’s entrance crowned with wildflowers, McKenna spoke in the dulled distracted voice of someone who could authentically be mad, exclaiming “Look, look, a mouse!” as if this vision were of great though unknowable importance. Unluckily, once the topic of dialogue turned to Goneril, McKenna allowed the irony to creep back in.

A second glimpse of what might have been McKenna gives us when Lear awakes after a long sleep in Act 4, scene 7. Here McKenna lends wear and humility to her voice in a way we have not heard and seems an entirely different person. McKenna keeps this welcome change of tone in operation through Lear’s heart-rending response to Cordelia’s death and almost to the end. It’s clear there is a fine Lear in McKenna – perhaps not right now and perhaps not until she is is ready to take more risks.

Hay is the first actor I have seen who clearly demonstrates the unintentional turning of her character toward its darkest side so that her Goneril appears in such a fog about her own motives that we almost pity her. In the division of the kingdom scene, Hay shows Goneril authentically shocked and dismayed by Lear’s request to say in public how much she loves him. She trembles, completely unsure whether she what she has said is even adequate. Later when she receives Lear’s horrendous curse for refusing to house his full train of knights, Hay stands stock still and weeping as she suffers such total public humiliation. It is primarily though her jealousy of Regan and Regan’s seeming strength that evil enters in. This is confirmed when Goneril, though married, longs for the attentions that Edmund gives Regan.

In contrast to Hay, Abbey has Diana Donnelly play Regan as evil from the very start. Donnelly’s Regan observes Goneril’s dismay, sees the game that Lear is playing and then proceeds to one-up her sister in declaring her love. Donnelly lends Regan an icy-hard voice and visage throughout as if never coming first in birth as Goneril or in love as Cordelia has caused her complete disbelief in kindness.

Mercedes Morris’s Cordelia, unfortunately, is one of the weakest performances in the play. The best Cordelias are angered by Lear’s love-test and vigorously refuse to play his game. Morris, however, meekly speaks her truth but is unable to show any emotion, either of love or anger behind it.

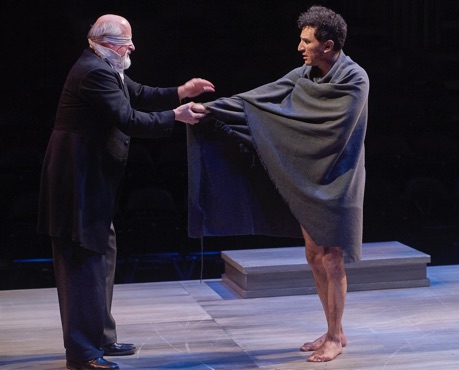

Among the parallel family to Lear and his daughters, Jim Mezon is wonderful as the Earl of Gloucester. While he has become a master at speaking Shaw, it is marvellous to hear him speak Shakespeare again with such technical and intellectual clarity. Mezon shows that Gloucester fits the same pattern of so many other good characters in the play – a flawed man who is spurred to heroic action by the sight of iniquity.

Antoine Yared gives what is so far his best-ever performance as Edgar. Perhaps because he does have to project in so large a space as the Festival Theatre, Yared uses a more rounded tone. He makes all of Edgar’s asides as “Poor Tom” register the distress that Edgar feels at seeing the downfall of Lear and then of his own father. Yared’s sympathetic performance helps make Gloucester’s false suicide at Dover one of the highlights of the play. Besides that, when Edgar feigns another voice as the man who discovers Gloucester at the bottom of the cliff, we find that Yared possesses a more modulated and deeper voice, one he should really adopt as his regular stage voice.

As Edgar’s half-brother Edmund, Alex McCooeye suffers from Abbey’s decision to direct the character’s first speeches as if they were fully comic. They are satiric but it is far better that Edmund speak them with deep bitterness, otherwise, as here, it seems he is meant to be a comic commentator on the action which is absolutely not the case. McCooeye is very effective as the evil, egotistical Edmund later on, but Abbey should have allowed Edmund’s true nature to be clear from the start.

In other roles, Kevin Hanchard makes Kent’s noble, righteous nature shine through even when when Kent is in disguise, while Augusto Bitter is a suitably officious Oswald. Alex Poch-Goldin is a chillingly evil Duke of Cornwall, well-suited to Donnelly’s icy Regan, while Karl Ang is sadly unable to give the Duke of Albany’s virtue enough heft to counterbalance much less negate the malice of his evil brother-in-law.

A further disappointment is the Fool of Colin Mochrie. The best productions of Lear make much of the friendship of Lear and his Fool with the sense that Lear allows the Fool such leniency in upbraiding Lear’s actions because at some deep level Lear knows the Fool speaks the truth. Without establishing such a bond, Lear’s exclamation over Cordelia’s body, “And my poor fool is hang’d!” loses the full impact of it’s double meaning. Mochrie speaks all the Fool’s lines clearly but Abbey has not encouraged the development of any emotional tie between Lear and the Fool at all, so that it really is unclear why Lear is so eager to have the fellow about him at all.

While Groundling Theatre’s Lear proves that one of the greatest roles in English drama should not be the exclusive preserve for men, it does not demonstrate that the present production is the best example of that revelation. This is not necessarily a production to avoid, but one should know that the play can be much more powerful than the present staging and, at its best, emotionally devastating. Anyone who saw Ian McKellan as Lear in 2007 in London or William Hutt as Lear in 1988 at Stratford should count themselves lucky to have had a fuller experience of what may be Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Seana McKenna as Lear and Jim Mezon as Gloucester; Deborah Hay as Goneril; Jim Mezon as Gloucester and Antoine Yared as Edgar. ©2018 Michael Cooper.

For tickets, visit http://www.harbourfrontcentre.com/whatson/today.cfm?id=9768&festival_id=0.

2018-01-14

Lear