Reviews 2018

✭✭✭✭✩

choreographed and directed by Akram Khan, music by Vincenzo Lamagna

• Akram Khan Company, Bluma Appel Theatre, Toronto

October 18-21, 2018;

• Lincoln Center, New York, NY

October 31-November 1, 2018;

-

•Place des Arts, Montreal, QC

February 13-16, 2019

“This is not war. This is the end of the world”

Akram Khan has said that Xenos will be his last full-length dance piece. That alone is reason enough to see it. An even greater reason is that it is simply a phenomenal work of theatre that inextricably combines dance, music, design, lighting and staging to create a multilayered commentary on life lived in extremis. The piece was commissioned for the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I. But as the 65-minute-long work progresses, it becomes clear the that Khan’s insights apply to the stress of everyday life lived in a world of chaos.

Khan’s particular interest is in commemorating the 1.3 million troops from India that fought for the British Empire in the Great War. We know about the contribution of colonial troops from Canada and Australia, But most of us are shamefully ignorant of the contributions of troops from other parts of the Empire. Xenos (ξένος) which means “stranger” or “foreigner in Greek, explores the enormous disruption troops from India would have experienced in having to serve in the trenches of Europe.

When you enter the theatre Aditya Prakash and B.C. Manjunath are already entertaining the audience with improvisations of Indian music. The set behind them is a curved slope designed by Mirella Weingarten reaching to half the height of the proscenium. A set of chairs, a table, rugs and cushions give the impression of an outdoor concert. Without a break in the music, Khan enters stage right pulling a long heavy rope. When he reaches centre stage, he lets it go and it recedes offstage. Khan then proceeds to perform a fantastic sequence of kathak dance. In motion, his arms seem to alternate between being absolutely rigid or completely liquid. He turns at what seem impossibly rapid speeds but always returns to precisely the same pose he had taken just before the turn including precisely the same mudra (symbolic hand gesture) he had made positioned in precisely the same place. His mastery of rapid gestures and immaculate precision is simply breath-taking.

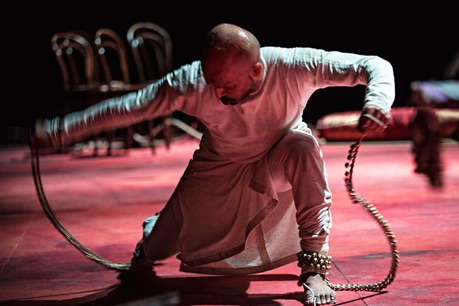

Periodically, there is a dull explosive sound and static as the ten bare light bulbs illuminating the stage flicker or even momentarily go out. Khan falters and falls to the ground. One time he falls and breaks the table but saves a small mound of earth from it and places it downstage centre. Khan’s gestures seem to become wilder. Eventually, after one explosion, Khan sits down and unwinds the series of ghungroos (rows of ankle bells) that had decorated each of his ankles. Khan then takes the ends of the ghungroos and fixes one around the toes of each foot. He then uses his hands to move himself as if manipulating himself as a marionette as if his culture had caused him to be treated no longer as a person but a puppet.

Finally, there is an especially loud explosion that causes the improvisations of Prakash and Manjunath to merge into the slow, eerie and menacing music of Vincenzo Lamagna for a special string quintet revealed behind a black scrim above the slope of the set.

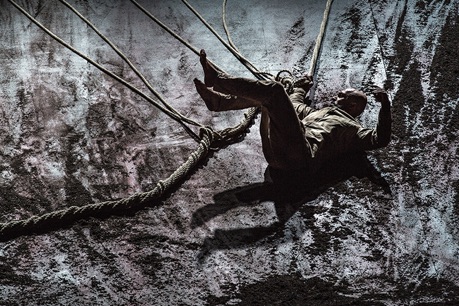

At this point there is a coup de théâtre. All of the objects on stage have been attached to ropes and as Lamagna’s music continues all the furniture, including rugs and cushions, is slowly pulled up the slope and over the top. A rope with a small noose captures one of Khan’s feet and begins to pull him up, too, as quantities dirt begin sliding down the slope. Symbolically, we see how the whole world Khan’s nameless soldier knows is pulled into the conflict and into the unknown. Khan himself is pulled against his will into what seems to be a huge trench that we feel lies behind the slope.

Once on top of the slope Khan encounters an oversized gramophone, symbolic of European technology. Khan has dragged a long rope in with him and when he sees the small cord dangling from the gramophone he ties them together to the sound of static. What emerges is a roll-call of Indian names. At the sound of each name, Khan agitates the rope so that a small ripple courses down its length. We then hear how an Indian soldier was laying a telephone cable down the length of a trench even though half the troops there were already dead. As the words “already dead” replay on the gramophone as if stuck in a record groove, Khan enacts the grief and despair of those in the trenches.

When the gramophone begins to play the old anti-war song, “Hanging on the Old Barbed Wire”, Khan movingly and disturbingly recreates with the help of ropes the landscape of men dead and caught on wire fences who were the first to exit the trenches.

Canadian Jordan Tannahill has written the text that Khan speaks although Khan speaks it so softly little of it is heard. An exception is Khan’s voice repeating, “I’ve been a soldier. I’ve killed and I’ve been killed. Again and again”, thus turning the single soldier he has been playing to every soldier. To the repetition of these words, Khan makes his way down the slope and concentrates on protecting the small mound of earth he had saved from the table near the start of the show. This action carries multiple meanings. Is Khan a colonial soldier protecting land gained by British troops? Is this Khan a colonial soldier protecting his memory of the land he had to leave to fight for the British? Is this a display of the absurdity of war that one man protects a bit of earth as he is surrounded by other bits of earth? Why is this bit special and all the rest not?

In the act of protection, Khan’s right hand begins to march across his left arm and onto the ground. Gradually, this small gesture turns into a fantastic battle played out with Khan’s very body of a struggle between his right half and his left. Though precisely calculated, in many ways this looks very like Khan miming the struggle of a man attempting to escape a straitjacket, with all the brilliant attendant meanings of mankind attempting to escape from the insanity of war. Khan’s soldier even creates a kind of full-face mask and turban out of the rope on stage as if demonstrating how the soldier is both tied to and ashamed of what he has done.

The piece ends with a sense of reconciliation when we hear the Lacrimosa from Mozart’s Requiem Mass in D minor (1791). The words “Lacrimosa dies illa / Qua resurget ex favilla / Judicandus homo reus” (“Full of tears will be that day / When from the ashes shall arise / The guilty man to be judged”). The dirt that has covered the stage receives yet another meaning as the resting place of both innocent and guilty alike. The show ends with another theatrical surprise when, from the seats so distant from the stage where I was, what looked like small balls cascaded down the slope. Not knowing what they were I assumed the piece ended on an extremely pessimistic note of the collapse of the world around Khan. When I saw what they were in the poster outside the theatre, I realized they represented just the opposite – a cause for hope and rebirth after destruction.

Xenos is an amazing work. Not only does it feature the impeccable dancing of Akram Khan but Khan fashions a huge array of meanings not just from the gestures of kathak and modern dance but from his brilliant use of just a few basic props. A slope, earth and ropes – these he builds through numerous contexts into a complex array of symbols, each comprehending in itself opposing meanings. Ropes are signs of traps but also safety as his ghungroos are of art and celebration. As a performer Khan explores these various and connected meanings in an attempt to comprehend what home and belonging really mean. How can anyone be considered a “foreigner” when we are live on the same earth, are made from it and return to it?

If you have never seen Akram Khan before, do not miss Xenos. If you have seen him before you will certainly want to revel in his dancing and supreme theatricality in this his last full-length work.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Akram Khan in Xenos; Akram Khan removes his ghungroos; Akram Khan in Xenos. ©2018 Jean-Louis Fernadez.

For tickets, visit www.canadianstage.com

2018-10-19

Xenos