Reviews 2018

✭✭✭✭✩

by Marc-Antoine Charpentier / Jean-Philippe Rameau, directed by Marshall Pynkoski

Opera Atelier, Elgin Theatre, Toronto

October 25-November 3, 2018;

Harris Theater, Chicago, IL

November 15-16, 2018

Pygmalion: “Règne, Amour, fais briller tes flammes”

Opera Atelier has debuted a new triple bill that combines two one-act operas it has staged before, though not on the same programme, with OA’s first ever commission of a new work. The three pieces work together beautifully, with the two operas making more sense when played together than with their previous pairings.

OA first staged Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s Actéon (1683) on its own in 1993. In 1998 it was paired with Lully’s music for Molière’s play Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (1670) and in 2005 as a curtain-raiser for Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (1689). OA first staged Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Pygmalion (1748) in 1990 with Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s monodrama Pygmalion et Galatée (1770). In 1999 it repeated this pair with Roland Petit’s ballet Le Jeune Homme et la mort (1946) choreographed to music by J.S. Bach.

With the current triple bill, OA has finally found a more essential connection between Actéon and Pygmalion than period of composition or variation on a theme. Now, as signalled by the chrysalis that designer Gerard Gauci has projected on the front curtain, OA has seen that it is the theme of transformation that unites the two. Not only that but the stories for both operas have a common source in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8 ad) – Acteon from Book III and Pygmalion from Book X. The pairing also contrasts the tragedy of Actéon with the comedy of Pygmalion.

Both plots are quite simple, but there is no doubt that Actéon has the greater depth. In Actéon, the title character (Colin Ainsworth), a hunter, stops to spy the goddess Diane (Mireille Asselin) bathing in a pool with her nymphs. When she discerns the interloper, she transforms him into a stag and he is chased and eaten by his own hounds. When Actéon’s comrades lament his death, the goddess Junon (Allyson McHardy) appears and explains that Diane was merely carrying out her wishes. Junon’s action was a vain attempt to take revenge on her husband Jupiter, who is currently in love with Europa, to whom Actéon is related.

In comparison, the plot of Pygmalion is almost rudimentary. Pygmalion (Ainsworth) is discovered already in love with the statue of Galatée (Meghan Lindsay), unnamed in the opera, that he has sculpted and lamenting the fact that he should be struck with such a fate. His once-beloved Céphise (McHardy) upbraids him for his lack of attention and his foolish new obsession. In response Pygmalion prays to Venus to brings the statue to life. In the original, Venus’s son Cupid, called simply “L’Amour”, does this. Pynkoski and Zingg have split L’Amour into two characters – Eros, dancer (Tyler Gledhill), brings Galatée to life while L’Amour (Asselin) unites Pygmalion and Galatée. Only reading the programme makes this clear, otherwise we assume that Gledhill’s character is acting on Asselin’s character’s orders which makes just as much sense. Much dancing and celebration by the populace and by L’Amour’s entourage follow the transformation and make up the majority of the work.

In between the two operas is a brand-new ballet called Inception for solo baroque violin and solo male dancer. Edwin Huizinga, the violinist and composer, leads dancer Tyler Gledhill playing Eros and sporting little save a pair of red wings, across the totally bare stage. During the performance Gledhill gracefully transforms into movement every twist and turn of Huizinga’s neo-baroque solo. As the short piece progresses the drops and legs for Pygmalion gradually move down into place so that by the end the empty space has been transformed into a stage – a simple but beautifully effective metatheatrical variation of the evening’s theme of metamorphosis. Gledhill’s appearance, wearing the same wings, as the counterpart to L’Amour in Pygmalion, further links the new work and the old together.

More than most OA offerings, the new triple bill is a showcase for dance as much as singing. Chief among the singers is Colin Ainsworth, who plays the title role in both operas. In Actéon he shifts from a carefree hunter to a man seized with horror as he watches himself transforming into a beast. Ainsworth makes this transformation aria “Mon cœur autrefois intrépide” absolutely chilling, with Actéon barely able to sing his final word before he loses his human voice.

In Pygmalion, Ainsworth traverses the emotional arc in reverse. He begins with Pygmalion’s anguish at his lot, but after Galatée’s transformation Ainsworth outdoes himself in expressions of wonder and joy. Pygmalion’s final aria “Règne, Amour, fais briller tes flammes” is probably the most demanding and Ainsworth handles its rising tide of ecstasy beautifully. Ainsworth’s high tenor has grown in depth and power over the years. Now his his top notes have a thrilling heroic ring.

Mireille Asselin lends her pure, limpid soprano to both Diane in Actéon and L’Amour in Pygmalion. Asselin well conveys all the hauteur and anger of a goddess famous for her chasteness in the first opera, and, in contrast, projects all the playfulness of Venus’s naughty son in the second.

Mezzo-soprano Allyson McHardy also keeps her roles quite distinct. In the first opera she delivers Junon’s aria “Son infortune est mon ouvrage” with a grandeur befitting the queen of the gods, yet she subtly suggests the combination of annoyance and shame at Jupiter’s infidelity that has driven her to take revenge on Actéon that she knows his friends will find unfair. As Pygmalion’s spurned lover Céphise, McHardy again conveys a complex mixture of emotions in her one short scene – continued love for Pygmalion and humiliation that he should love an inanimate object more than she. It is a pity that Rameau’s librettist, Ballot de Sauvot, did not find a way to bring Céphise back for some kind of reconciliation if only for the pleasure of hearing McHardy’s dark, smooth, velvety voice again.

In Actéon, soprano Meghan Lindsay is simply one of Diane’s nymphs, Aréthuse, who is chosen for various short solos. As Galatée in Pygmalion she has a role that requires a high degree of vocal and physical stamina. For the first section of the opera Lindsay holds her pose as a statue so rigidly that some may even mistake her for one. The acting she brings to the statue’s coming to life is beyond what one often encounters in the best productions of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale where the statue of Hermione also comes to life. Lindsay shows us the wonder Galatée feels on being able to breathe for the first time, the marvel of singing, the awkwardness of taking her first steps and the joy of progressing so far she is able to dance. All the while Lindsay’s clear, strong voice beautifully conveys the Galatée’s emotions with each new experience.

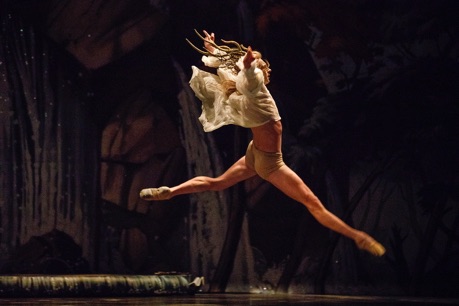

Dance is so much a part of both operas it is delightful to see how perfectly Asselin, McHardy and Lindsay are able to integrate themselves into the varied dances that Jeannette Lajeunesse Zingg has choreographed. Yet, it is suitable in Actéon that as the character’s metamorphosis begins, Ainsworth should rush off stage only to be replaced by dancer Edward Tracz performing virtuoso leaps and turns all the while supporting a large rack of frightening antlers skilfully designed by milliner Leslie Norgate and OA’s Head of Wigs, Jacqueline Cull.

While Zingg employs 19th-century classic technique of evading the floor to Tracz’s solo in Actéon, she moves forward to the 20th century for Tyler Gledhill’s sensitive solo in Inception which, despite his wings, is much more floor-oriented.

As usual, David Fallis draws gorgeous playing from the Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra producing a richness and warmth of sound that one did not think possible at the start of the period instrument movement. The Chorus of the University of Toronto Schola Cantorum with members of the Choir of the Theatre of Early Music, led by Daniel Taylor, provide the lush, precise choral contributions.

While the evening is studded with superb singing, it is also a reminder of how important dance is to Opera Atelier and how its integration into opera has helped make the company so unique not just among baroque opera companies but among opera companies in general. Opera (the plural of the Latin “opus” meaning work of art) was originally invented as a means of combining all the arts in one to tell a story. Opera Atelier has maintained true to the origins of opera and we have been all the more blessed for it.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Tyler Gledhill as Eros, Meghan Lindsay as Galatée and Colin Ainsworth as Pygmalion; Edwin Huizinga (violin) with dancer Tyler Gledhill as Eros; Edward Tracz as Actéon. ©2018 Bruce Zinger.

For tickets, visit https://operaatelier.com

2018-10-28

Actéon / Pygmalion