Reviews 2018

✭✭✭✭✭

by Slava Polunin, directed by Viktor Kramer

• Show One Productions, Bluma Appel Theatre, Toronto

December 7-16, 2018;

• Théâtre St-Denis, Montreal

December 19, 2018-January 6, 2019;

-

•Stephen Sondheim Theatre, New York, NY

November 14, 2019-January 5, 2020

“Sors salutis

et virtutis

michi nunc contraria,

est affectus

et defectus

semper in angaria”

(from “O Fortuna”, Carmina Burana)

Slava’s Snowshow has been going strong since its world premiere at the Edinburgh Festival in 1996. The entertainment by Russian master clown Slava Polunin is undoubtedly the most popular full-length clown show ever created. It was last seen in Toronto in 1999. If you saw it then, you will certainly want to see it again. If you missed it then, don’t miss it this time.

The wordless show is accompanied by a varied selection of pre-recorded music mostly melancholy in nature. Slava as his clown alter-ego Assissiaï enters downcast and holding a noose. The comedy is that the rope is so long that Slava has to gather it up in in several coils. Since there are no trees in sight, we wonder where Slava plans to do himself in. Viktor Plotnikov’s set looks like seven upright mattresses with stars printed on them and gives the impression both of a padded cell for madmen and of an otherworldly space. To give away the show’s first gag, Slava keeps tugging of the rope until pulls in the show’s second lead clown (Nikolai Terentiev) who already has a noose around his neck. Thus we are introduced the mordant, absurdist humour that characterizes the whole show. We are also introduced to the first of a succession of circles, balls and falling that give the show its gorgeous visual harmony.

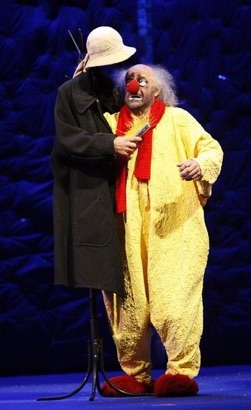

Though Slava’s Snowshow does not tell a story, the connection of its sequence of skits does suggest that after Slava and his fellow clown discover they both planned to commit suicide, they then try to see what the world has to offer to cheer them up enough to change their minds. Slava is dressed in a baggy yellow one-piece outfit with a red scarf and fluffy red, slipper-like shoes to match his red nose. He is bald on top but the profuse grey hair on the sides grows out horizontally from his head. Slava stands out from all the other clowns, including his companions, who are dressed in baggy mid-calf green overcoats and wear hats with oversized earflaps that stick out horizontally two or three feet from the hats. The Green Clowns also wear shoes about three feet longer than an ordinary shoe.

After a fall of glitter to suggest rain followed by hoards of soap bubbles blown in from the wings, Slava and Nikolai sail in to Vangelis’ heroic music for Chariots of Fire on a red metal bed with a red broom for a bowsprit and an old sheet for a mast. This is a perfect example of the childlike world of imagination the show conjures up as a balance to its adult-like melancholy. Nikolai and another Green Clown enter with Slava, play squeeze-boxes and lip-synch to the silly 1950s song “Blue Canary” to try to cheer Slava up which comically happens to Slava in spite of himself until he is finally lip-synching along.

Slava has two encounters with spinning balls. With one small one that swings he manages to get his head out of the way just in time. When it is spinning he pretends he is spinning it on the tip of his red nose. The next incident happens with the old ash-can that has been the only prop on the set and is the place the tramp-like clowns gather to warm themselves. Gradually a yellow hemisphere rises that we think may represent the fire. But it turns out to be a globe that slowly rises straight from the can out of sight.

Much humour in the show derives from Slava’s disdain of the behaviour of the Green Clowns, the irony being that they are all so low on the hierarchy of power that it seems absurd that anyone should try to dictate proper behaviour to anyone else. In a great scene Slava and Nikolai happen to meet but have have forgotten how two people greet each other. They know it involves one person rubbing part of himself on the other, and the two proceed to experiment (non-sexually) and go to hilarious lengths.

This show is not at all ideal for people with coulrophobia. In fact it will only encourage it because the clowns do not stay safely on stage away from the audience. In Act 1, Slava himself makes his way into the audience walking on the backs or arms of the seats, often using the hands of audience members for support. In Act 2, from the point of view of a coulrophobe, things get even worse. All seven of the Green Clowns invade the audience with bins of paper “snow” that they liberally scatter on audience members of simply dump on a single audience member. If that were not enough they emerge again with tattered green umbrellas. That’s not so bad we think. Wrong! They’ve inverted plastic water bottles on the finials of their umbrellas so that when the spin them water splashes everyone around. Note: there’s no point in dressing up for this show.

In these ways the show rids the audience of any smugness it may have about being any different from the clowns on stage. We are merely the clowns in the audience. A great example occurs just at the end of Act 1. Slava indulges in the typical clown trope of touching something sticky on one of the mattress-like panels of the set and then gets so bothered in trying to rid himself of it that he becomes almost cocooned in its web. We may laugh, but little do we know that Slava has a massive revenge for our ridicule in store that engulfs the entire audience.

Yet Slava can take another clown trope and play it to its utmost seriousness. There is a woman’s hat and coat on a coat stand. Slava puts his left arm through the left sleeve of the coat and magically he becomes two people, a woman and a man in love. I have seen others do this routine many times before but watching Slava sent a shiver when down my spine when the right arm in the coat moved so independently from Slava that for a minute I actually thought I saw two people there.

The “woman” slides a train ticket into Slava’s pocket, presumably to meet him at the destination, but Slava is devastated to find she is not there. He tears the ticket up into little pieces, throws them into the air and this unleashes the famous unimaginably huge snowstorm to Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana that then engulfs the entire audience. It’s fitting that the storm starts with the words in “O Fortuna” that translate as “Fate is against me / in health / and virtue, / driven on / and weighted down, always enslaved”. True to the double nature of the show that gives it its depth, what we experience as exhilarating and uplifting, is, in fact, an infinite magnification of Slava’s sorrow.

Though the show may involve a crew of scruffy, bizarre-looking clowns, the scenes that lighting technician Alexander Iakovlev creates are often exquisitely beautiful. Often he silhouettes the performers against the background as if to underscore their insubstantiality. His lighting for the famous snowstorm is amazing as is his scene setting for the major surprise that follows it. Slava has said he wanted to create “A show which would help spectators be released from the jail of adulthood and rediscover their forgotten childhood”.

That is exactly what happens at the end as the show passes from a passive to an active experience. The show brings ecstasies to the children in the audience and liberates the inner children of their accompanying adults so that you relive what it was like to be a child again. It is no wonder that Slava’s Snowshow has delighted audiences all over the world by reminding adults that that they have not really left their childhood behind. They have merely allowed it to languish until someone like Slava Polunin brings it back to life.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Slava Polunin as Slava, ©V. Vial; Slava and a Green Clown sailing, ©2014 Guilio GMDB; Slava and friend, ©Eva Miglioli.

For tickets, visit https://showoneproductions.ca or

https://theatrestdenis.com/en/event/slava-snowshow or https://slavaonbroadway.com

2018-12-09

Slava's Snowshow