Reviews 2018

✭✭✭✭✩

by Pierre Corneille, directed by Joël Beddows

Théâtre français de Toronto, Berkeley Street Theatre Upstairs, Toronto

April 13-22, 2018

Cliton: “Les menteurs les plus grands disent vrai quelquefois”

To conclude its 50th season the Théâtre français de Toronto has chosen to present its first-ever Corneille. Falling in the traditional Molière slot at the end of the season is Le Menteur, a comedy from 1644 by Pierre Corneille (1606-84), best known as the author of the Le Cid (1636) that inaugurated the neoclassical period of drama in France. Le Menteur precedes Molière’s first great play Les Précieuses ridicules (1659) by fifteen years and gives us a very different view of 17th-century French comedy. The TfT has fielded a superlative cast who under Joël Beddows’s direction astutely bring out the ambiguities of Corneille’s provocative, strangely modern play.

Corneille based Le Menteur on the Spanish play La verdad sospechosa (pub. 1634), the best-known play by Mexican author Juan Ruíz de Alcarón (c.1580-1639) that also inspired adaptations by famous authors in Italy and England. In Corneille’s play the title character is Dorante (Nico Racicot), who has just arrived in Paris for the first time after giving up his law studies in Poitiers. He is basically a boy from the provinces who longs to make himself famous in the big city. A compulsive liar, he is keenly aware of his lack of an interesting background and defends his lying as the the only way he can make an impression.

As his first adventure, he and his valet Cliton (François Macdonald) go for a walk in the Tuileries. There they meet two young women, Clarice (Valérie Descheneaux) and Lucrèce (Shiong-En Chan), and Dorante immediately falls in love with the more talkative of the two and she, apparently, is not indifferent to his persistent attentions. To impress her Dorante claims he is just back from fighting in Germany (likely in the Thirty Years War) and that he has been in Paris for a year watching her and waiting to speak to her because he is in love.

After the women leave, Cliton goes to ask their coachman the names of the women. He says that the more beautiful of the two is called Lucrèce and the other Clarice. Based on this ambiguous information, Dorante immediately assumes his interlocutor was Lucrèce (whereas, in fact, it was Clarice).

Dorante’s flirtation with Clarice instantly gets him in trouble since Dorante’s friend Alcippe (Alex Côté) has already been promised to Clarice in marriage. The problem is that Alcippe and Clarice have been waiting for two years for Alcippe’s father to make the trip to Paris so they can marry. Unaware of this, Dorante enrages Alcippe by claiming that he has recently entertained Alcippe’s fiancée with a lavish party on the Seine.

Meanwhile, Clarice has become tired of waiting for Alcippe’s father to arrive and Dorante’s father Géronte (Guy Mignault) suggests that should the marriage be called off, he would like to suggest his own son as her new fiancé. Seeing that Dorante is his son, Clarice is pleased. Dorante, however, on learning that his father wishes him to marry “Clarice”, is not pleased since Dorante thinks he is in love with “Lucrèce”. As a way of foiling his father’s plan, Dorante tells him that he can marry no one because he is already married and makes up an extraordinarily involved story of a misadventure in Poitiers that brought this about.

While Géronte is happy to hear that Dorante is married, this news of course, enrages Clarice which leads Dorante to explain his “marriage” away with a whole new series of lies. As the action progresses we increasingly wonder when and how Dorante will be finally entrapped by the web of lies he has spun.

What makes Dorante so different is that he is just a young man out of university unlike all of Molière’s monomaniacs who are either middle aged or elderly. In Le Menteur, in total contrast to Molière, the usually insipid young male lover has become the play’s primary blocking figure. As a result, contrary to the usual course of comedy in which youth triumphs over the rules of the old, in Le Menteur youth succumbs to the older generation’s dictates. Corneille portrays Dorante in a non-Molièrean fashion by allowing our perception of the character to become increasingly negative in the course of the action.

This becomes particularly evident in a scene more like that in a tragedy than a comedy in which Géronte delivers a poignant plea as a father and an aristocrat to Dorante to behave in a more honourable manner. When Dorante foolishly laughs off this advice, what little sympathy we had for him vanishes. It is a fascinating dramatic ploy typical of Corneille’s interest in pushing the boundaries of dramatic genres in a manner quite unlike Molière. One can only wonder what French 17th-century comedy would have been like if Corneille had chosen to focus on comedy rather than tragedy. Just as in Le Cid where Corneille wrote a “tragedy” with a happy ending, in Le Menteur Corneille wrote a “comedy” with an ending that may not be tragic but is far more ironic that anything in Molière. In fact, its ending is much like the ending of some of Shakespeare’s so-called “problem plays” Measure for Measure or All’s Well That Ends Well, where the play concludes with multiple marriages, as do comedies, but where those couples have to be viewed as far from happy.

Beddows and his designer Melanie McNeill have set the action in a kind of alternative present where men wear floral patterns and women plain colours. McNeill’s clever costume for Dorante makes him look as if he has a cape slung over one shoulder when it is really just extra fabric extending from his jacket. McNeill’s set features neon lights including a crescent moon and a star on the back wall that are seen through three layers of translucent plastic curtains. The idea may be to embody the way in which Dorante’s accumulation of lies increasingly befog the truth. That interpretation is contradicted, though, by the power Beddows gives Dorante to turn on the neon lights or the stage lights with a snap of his fingers as if he were in control. This is a rather confusing power to give him since Dorante should be seen as barely in control of his own life let alone of the entire stage.

One of the great virtues of this production is its cast. They speak Corneille’s muscular French couplets with such clarity and understanding that, if you are Anglophone but know French, you will find little reason to glance at the English surtitles. You can’t help but wonder why the young actors at Stratford aren’t able to speak Shakespeare as well as these young actors speak Corneille.

Nico Racicot plays Dorante as a scoundrel from the beginning, lovable at first but increasingly unlikable as the action proceeds. The question the play poses is why Dorante is such an inveterate liar. Initially, Racicot makes it appear that Dorante feels lies are necessary to make him appear more attractive in the eyes of experienced Parisian women. Yet, Dorante also lies to get himself out of trouble and, in speaking to Alcippe, to goad his former friend deliberately into anger. In Racicot’s hands Dorante’s behaviour remains outrageous from start to finish, rather as if Dorante told lies to prove to himself what fools other people are in believing him.

Yet, this could be a richer role than Beddows or Racicot have imagined. Most compulsive liars lie because they are deeply unhappy with their lives as they are and use lies for self-aggrandizement. Racicot is so good in projecting Dorante as a rogue that he could easily have made the character more complex by giving us a glimpse at the insecurities that must underlie Dorante’s ultimately self-destructive behaviour. Beddows seems to want us never to sympathize with Dorante, but a view of the character’s complexity would go a long way to making Dorante a more intriguing figure.

François Macdonald is well cast as Dorante’s valet Cliton, a young man who is a plain-speaker as much as his master is not. Macdonald lends Cliton a charming naïveté showing that even he can still be taken in by Dorante’s lies. One is tempted to see the Dorante-Cliton relationship as a precursor of the Dom Juan-Sganarelle relationship in Molière’s Dom Juan, except that Macdonald suggests that Cliton remains with Dorante not because Dorante still owes him money but because they are much more friends than master and servant and Cliton seeks, in vain, to protect Dorante from the effects of Dorante’s mendaciousness.

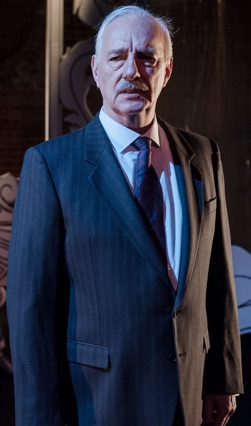

The outstanding performance of the evening comes from none other than Guy Mignault, Joël Beddows’s immediate predecessor as Artistic Director of the TfT. Mignault lends the scene where Géronte castigates Dorante for deceiving him enormous emotional power that goes far beyond what one might expect in a comedy. Mignault creates a portrait of fatherly love and honour betrayed that inseparably mixes Géronte’s pain, embarrassment and outrage. Kudos to Beddows for not trying to make the scene comic in any way and to Mignault for so perfectly conveying Géronte’s complex emotions.

In other roles, Alex Côté is an energetic Alcippe, a young man who is constantly on the verge of losing his self-control. Nabil Traboulsi well plays the ever reasonable Philiste, who tries to make peace between Dorante and Alcippe. And Inka Malovic clearly distinguishes between the bookish Isabelle, Clarice’s maid, and the sensuous Sabine, Lucrèce’s maid. The only problem is that for those unfamiliar with the play, some may think that Isabelle is actually disguising herself in a comic way rather than that Malovic is playing two different characters.

Corneille is always taught as one of the three great French playwrights of the 17th century, yet his plays are far less performed than those of his contemporaries Racine and Molière. This is a pity since Corneille, unlike the other two was interested in expanding what the genres of tragedy and comedy could do instead of conforming to Richelieu’s “rules” for the two genres.

The Stratford Festival has staged two plays by Corneille, Le Menteur as The Liar in 2006 and the charming L’Illusion comique as The Illusion in 1993. The rare chance to see Corneille performed at all, let alone in the original (with English surtitles), and in Ontario and in a provocative production is reason enough for theatre-lovers to see this TfT production. Seeing what other approaches to comedy there are in classical French drama as in Corneille’s fascinating play make one hunger for more variety like this in the traditional programming slot for Molière that clearly should not be reserved for Molière alone.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive

Photos: (from top) Nico Racicot as Dorante, Nabil Traboulsi as Philiste and Alex Côté as Alcippe; Nico Racicot as Dorante and François Macdonald as Cliton; Shiong-En Chan as Lucrèce and Valérie Descheneaux as Clarice; Guy Mignault as Géronte. ©2018 Marc Lemyre.

For tickets, visit http://theatrefrancais.com.

2018-04-15

Le Menteur