Reviews 2018

✭✭✩✩✩

by Erin Shields, directed by Jackie Maxwell

Stratford Festival, Studio Theatre, Stratford

August 17-October 27, 2018

Satan: “Evil, be thou my good” (Book IV)

Anyone attending Erin Shields’s Paradise Lost expecting to see an adaptation of John Milton’s great 17th-century epic poem, will be disappointed that the play is almost entirely about Shields and only tangentially about Milton. To be fair to an audience the play should be titled Paradise Lost: A Burlesque, because that is what it is. Shields takes clichés and prejudices about Milton’s poem and its subject matter for truths and then mocks them. The play only follows the plot outline of the poem and cannot even qualify as a superficial reading of it. Instead, it is merely a series of comic riffs on subjects suggested by the poem. An audience will emerge from the show no wiser about Milton’s work or why it is important than when it went in.

Paradise Lost, published in its final form in 1674, is a work that anyone who has not read or studied it can find very easy to mock. It is, after all, an epic poem where the central action is a woman eating a piece of fruit. The poem is, moreover, written by a Puritan who claims that he wants to “Justify the ways of God to Man”. For many people that fact alone would be so off-putting that they would read no further. Yet, anyone who is able to set aside prejudice and read what Milton actually wrote will discover that the poem has no less a purpose than to explain the nature of the universe and mankind’s place in it.

Milton may have been a Puritan but people should remember that one of his greatest prose works is the Areopagitica of 1644, an impassioned defence of free speech. Far from imposing doctrine, he speaks out against censorship: “I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and sees her adversary ...”. Anyone who studies his Paradise Lost closely will realize that it, too, is far from doctrinaire but rather proposes one of the most radical interpretations of the fall of mankind ever written. It is depressing, therefore, that someone as talented as Shields should not even inquire into what Milton’s poem is about but merely use it as a framework of a series of comic skits.

To reach Earth, Satan has to escape imprisonment in Hell. As it happens the gatekeepers of Hell are Satan’s own daughter, the slatternly Sin (Sarah Dodd), and her son, the dimwitted Death (Devon MacKinnon), amusingly characterized by Shields as trailer trash. Satan convinces them that if they let him out he will return for them and take them to Earth. Satan then disguises herself as a Cherub to get past the Archangel Uriel (a noble Beryl Bain), who stands guard at the Sun.

Before deciding how to tempt Adam (Qasim Khan) and Eve (Amelia Sargisson), Satan observes them. Here Shields has fun satirizing the inanities of their happy life. They are blissfully in love and work tending the Garden of Eden but need not work so much that it could really be called work. In a detail that contradicts her own portrayal of Eden, the two enjoy all the fruits of the Garden including lamb chops, which makes no sense since, as Shields later shows, animals did not eat each other until after the Fall.

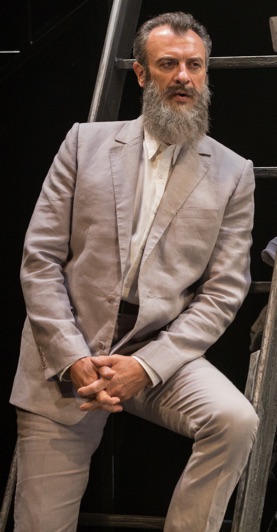

Shifting the scene to Heaven we meet God (an imperious Juan Chioran) and the Messiah (a compassionate Gordon S. Miller), who is actually called only the Son in Milton’s poem. The Son informs God of Satan’s movements to which he keeps answering “I know” – Shields’s comic way of showing that God is omniscient. God decides to send the Archangel Raphael (Michael Spencer-Davis) to Earth to warn Adam and Eve of the danger they are in. Shields has the idea to make Raphael an amateur playwright so that instead of explaining the War in Heaven as happens in Milton, Raphael has written a drama about it to perform for the two humans.

This play-within-a-play is the most hilarious part of Shields’s adaptation although it relies heavily on the Mechanicals’ play in A Midsummer Night’s Dream for inspiration with Raphael as an angelic version of Peter Quince. The main knowledge we gain is that Satan used to think of herself as God’s most beloved angel until God introduced the angels to his Son. It was Satan’s pride that caused her to rebel and to rally a third of the angels against God, who were then all single-handedly defeated by the Son. Raphael’s play itself does not go well, especially when the real Satan appears in the role of Satan and frightens everyone.

Satan discovers that Adam and Eve can eat from all the trees in the Garden except from the Tree of Knowledge, the penalty for which is death. Her plan is thus formed and when Adam and Eve work separately one day, Satan disguised as a serpent tempts Eve to eat the forbidden fruit. When Adam discovers what Eve has done, he feels that he must eat of it, too, since he loves Eve so much he does not want to be alone. As one of her many jokes, some of the knowledge Adam gains includes thinking the Earth is flat and that the sun and planets revolve around it. This only suggests that the knowledge from the Tree of Knowledge is not worth acquiring, which is funny for a moment until you realize it runs counter to the whole point of the story.

God sends the Son to punish the first couple and burdens Eve not just with pain in childbirth and submission to her husband, but, comically, with numerous contemporary complaints like always being interrupted by men at meetings. The Archangel Michael is sent to drive the disobedient pair out of Paradise but not before granting Adam a vision of what will follow taking him through the Book of Genesis and mentioning the Son’s plan to sacrifice himself to save mankind.

Shields adds her own postscript to the action with a dialogue between God and Satan. Here Satan discovers, as she should already have known, that because of God’s omniscience he knew of it all, including her rebellion and her plans for revenge, before it happened. Satan thus accuses God of trying to keep his name clean by allowing her to do all his dirty work for him, to which God replies that she can think what she will.

While much of Shields’s invention has been quite humorous, this ending is extremely unsatisfying both for those who know the Bible and especially for those who know Milton. The most obvious omission is that Shields neglects to show God’s punishment of Satan by turning her into a snake. Shields shows all the rest of the rebel angels thus transformed but not Satan.

Shields knows that Satan is God’s creation and that Satan, like God’s other creatures capable of reason, has free will. Without free will Satan would not have been able to rebel. Without free will Eve would not have been able to eat from the forbidden tree. This is part of the price of freedom. As Milton’s God says of Satan, “I made him just and right, Sufficient to have stood, though free to fall. Such I created all the ethereal Powers And Spirits” (Book III).

Though Shields acknowledges that God already had foreknowledge of the events that would happen before he created angels and humans, all Shields sees is that human beings are trapped by modern religious prohibitions, which gives her much material for satire but misses the whole point of Milton’s epic. The poem is about freedom. And if God is omniscient he knows that mankind will choose freedom and knowledge even if the price is death. Indeed, death only makes life more precious.

Shields also totally ignores Milton’s central interpretation of the Fall of Mankind. She portrays it in the narrowest possible way as the event that leads inevitably to our present unhappy world. Milton, however, looks at the Fall of Mankind from a universal perspective and sees it as a felix culpa or “fortunate fall”. Mankind may give up blissful ignorance and security, but the knowledge and the capacity for suffering it gains outweighs what it loses. Significantly, Shields omits one of the most important passages in Milton’s poem. Near the end of the epic Raphael says:

[O]nly add

Deeds to thy knowledge answerable; add faith,

Add virtue, patience, temperance; add love,

By name to come called charity, the soul

Of all the rest: then wilt thou not be loath

To leave this Paradise, but shalt possess

A Paradise within thee, happier far. (Book XII)

This is the most radical aspect of Milton’s poem. Adam and Eve may lose the physical Paradise they lived in in ignorance, but what they gain is a “Paradise within” to which they always have access. What Milton audaciously suggests is that by disobeying God, Adam and Eve attain a state that is better than the Paradise they had before. This is hardly the strictly Puritan or even traditionally Christian viewpoint that Shields so lustily satirizes, but a statement of the ultimate freedom of the individual that nothing can diminish.

By missing this point, Shields shows she does not understand the poem. I don’t mind a satire of a work that an author understands. I can’t abide a satire of a work an author does not or can’t be bothered to understand. Shields is free to portray God as a tyrant with his angels automatically chanting “Wise are his ways” as a salute whenever his name is mentioned. But that portrayal goes contrary to everything Milton’s poem depicts.

Luckily, the play is blessed with fine performances from the entire cast, with Peacock’s wry, unsavoury talkshow host-like Satan a particular standout. It’s too bad Judith Bowden’s design for Heaven, Hell and Earth, made up of a mass of shirts sinking down from a trellis into a pile near a ladder with neon-lit rails, is unattractive and signifies nothing.

Audiences attending a Shakespeare Festival will likely expect a serious engagement with Milton’s epic rather than what feels like a sophomoric protest against having to read a difficult poem. Rather than commissioning a play on the subject from Shields, the Festival need simply to have invited Montreal’s Paul Van Dyck to bring his multi-award-winning version of Paradise Lost to Stratford. Touring since its premiere in 2009, Van Dyck’s version, in which he plays all the roles, successfully dramatizes Milton’s poem using only carefully selected excerpts from the text itself. Unlike Shields’s play, Van Dyck’s more theatrical version hones in on the power and inherent drama of Milton’s verse and emphasizes Milton’s radical interpretation of the story. In so doing Van Dyck accomplishes more in only one hour than Shields does in a bloated 2 hours and forty minutes.

If all you are looking for in a show named Paradise Lost is light entertainment and a few laughs at subpar sketches suggested by Milton’s poem, then Shields’s play will fit the bill. If, however, you want to see how Milton’s poem itself can be brought to exciting theatrical life, then keep an eye open for the next tour of Van Dyck’s brilliant version. It has visited Toronto twice and, one hopes, will return again.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Lucy Peacock as Satan; Amelia Sargisson as Eve and Qasim Khan as Adam; Juan Chioran as God the Father. ©2018 Cylla von Tiedemann.

For tickets, visit www.stratfordfestival.ca.

2018-08-31

Paradise Lost