Reviews 2018

✭✭✭✭✩

music & lyrics by Robert Wright and George Forrest, book by Luther Davis, directed by Eda Holmes

Shaw Festival, Festival Theatre, Niagara-on-the-Lake

May 27-October 14, 2018

Doctor: “For all of them time is running out”

The Shaw Festival’s big musical this year is a rare revival of Grand Hotel by Robert Wright and George Forrest as revised and expanded by Maury Yeston. The musical is based on Menschen im Hotel (“people in a hotel”), the international 1929 bestselling novel by Austrian author Vicki Baum (1888-1960), the 1930 hit play she adapted from it and the 1932 Hollywood movie Grand Hotel based on the play that won the Oscar for Best Picture that year. The music is lush and the storylines melodramatic, but they suit a show about the fervour of life in a luxurious hotel in Berlin in 1928, a world on the brink of collapse and a descent into darkness.

Grand Hotel, as novel, play and film, is famous for inaugurating a new way of constructing narratives based on the gathering of strangers in the same place and following their interactions. Whether the strangers are held hostage as in The Petrified Forest (1935), invited to a house party by a mysterious host as in And Then There Were None (1939), snowbound as in Bus Stop (1955) or thrown together by disaster as in The Poseidon Adventure (1972), this form still endures today.

In Grand Hotel the musical this structure is especially interesting since on first meeting the six characters we will follow, we have no idea how their separate fates will become entwined. The most dashing guest is the Baron Felix von Gaigern (James Daly), a man with a title but no money, who is already seven months in arrears for his hotel bill and is hounded by a mysterious man posing as his Chauffeur (Jeff Irving), to pay a larger outstanding debt.

Just his opposite is the mousy, terminally ill bookkeeper Otto Kringelein (Michael Therriault), who has left hospital and withdrawn all his considerable savings to stay at the Grand Hotel, where he hopes for once in his existence to experience “life” and luxury.

Less happy than either the Baron or Kringelein is Kringelein’s former employer Hermann Preysing (Jay Turvey), whose future in business will be destroyed if a company in Boston rejects his company’s offer of a merger.

Also staying in the hotel is the once-renowned ballerina Elizaveta Grushinskaya (Deborah Hay), now on her eighth farewell tour, who knows she is long past her prime and that audiences no longer wish to see her. Pressing her to keep going on is her devoted assistant Raffaela (Patty Jamieson), who has been keeping the depth of her love for Elizaveta a secret.

The youngest of the six, though not initially a guest in the hotel, is the typist Frieda Flamm (Vanessa Sears), who dreams of being a movie star in Hollywood and has already chosen “Flaemmchen” (“little flame”) as the name she will be known by. She desperately wants to earn enough money to go to the US.

As Colonel-Doctor (Steven Sutcliffe), named Doctor Otternschlag in the novel, play and film, observes, “For all of them time is running out”. And just as time is running out for each of the main characters it is running out for the world in general in this last year before the great stock market crash of 1929.

If people know the story of Grand Hotel at all, it will likely be from the 1932 film where, unfortunately, the Expressionist point of view has been eliminated in favour of Hollywood-style realism. Luther Davis’s insightful book for the musical reinstates the novel’s Expressionism by emphasizing that we see everything happening on stage through the eyes of the Colonel-Doctor, a World War I veteran who is addicted to the morphine he uses to numb the pain from his injuries. Director Eda Holmes ensures that we know we see things from his point of view by having him present on stage throughout, looking on from the shadows even on the most private scenes between characters.

Luther Davis’s use of an drug-addicted narrator and Holmes perception of its importance helps make the feverish, melodramatic nature of the action understandable. Throughout the show a dominant theme is the flimsy border between fact and fiction. Raffaela and Elizaveta’s manager (Allan Louis) feed Elizaveta false views of her current popularity. Preysing feeds his stockholders a false view of the company’s health. Flaemmchen’s dream of being able to travel to the US suddenly comes true only to turn into a nightmare. And, strangest of all, the Baron’s feigned love for Elizaveta turns into real love. All of these incidents makes sense in a world with such a tenuous hold on reality.

The music of Wright, Forrest and Yeston reinforces this air of unreality by being nearly continuous throughout the work. The music is all based on popular dances which morph into each other during certain songs and which the orchestra continues to play as underscoring for the dialogue. If dance is thought of as an escape from reality, the composers present the actions as one long, unending dance. Since even the youngest character remarks, “We all are dying aren’t we?” to Kringelein, the musical’s continuous dance, especially in its German setting, could be considered a kind of modern Totentanz.

The show has an excellent cast. Steven Sutcliffe’s Colonel-Doctor is a man so imbued with cynicism that he is simultaneously fascinated and appalled by the foibles of his fellow human beings. Though he decides each day whether he will continue to live, it seems, despite his scorn that his fascination with humanity impels him to live another day.

As the Baron, James Daly looks too young for someone trying to pretend he is under 30. He presents the Baron as a young man open to anything, which helps explain his friendship with a non-entity like Kringelein, but his manner is rather too sunny. When the Chauffeur suggests that he steal from other guests, we should think that this is something he has done before. Daly also doesn’t quite pull off the difficulty task of distinguishing the Baron’s false love for Elizaveta from his true love. Yet, Daly cuts such a dashing figure and sings so well, we tend to forget that his characterization is not as layered as it should be.

Deborah Hay, however, is magnificent as Elizaveta and makes the part fully her own. An emotionally and spiritually fragile person who needs constantly bolstering from her entourage could appear as a negative figure, but Hay shows us that her need arises from deep inner pain and knowledge of her own self-deception. It is the most emotionally complex performance of the evening and her intense account of “Bonjour Amour” brings down the house.

Michael Therriault gives an endearing performance as Kringelein, a man who is experiencing the grand life for the first time. Therriault minimizes the inherent sentimentality of the part through the naturalness and simplicity of his acting that makes us focus on the new pleasures he is feeling rather than on his tragic circumstances.

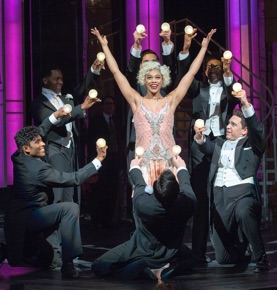

Vanessa Sears successfully takes her character Flaemmchen through a wide emotional range – from the naïveté of her dreams of stardom and her self-confidence as a New Woman ready to meet men on her own terms to her anger at being objectified to her chastened nature at the end and realization that not all good things may be the ones you seek. Sears has a real star-making turn in the flashy song-and-dance number “Girl in the Mirror”.

Jay Turvey well plays the morally weak businessman Preysing, but isn’t really able to summon up enough creepiness when it’s time to reveal Preysing’s darker side. Patty Jamieson is a sympathetic Raffaela. We guess before she says anything what the source is of her devotion to Elizaveta. Jamieson lets us see that Raffaela knows the hopelessness of her love and now, after 22 years of service, it is too late to reveal it. Jamieson invests both her numbers “Twenty-Two Years” and “How Can I Tell Her?” with a sadness tempered by a sense of duty.

In other roles, Travis Seetoo is quietly sensitive as the hotel clerk Erik Litnauer, whose manager won’t allow him to visit his wife who is due to give birth. Jeff Irving is coldly menacing as the supposed “Chauffeur” who keeps putting pressure on the Baron to steal to pay his debts. And Matt Nethersole and Kiera Sangster are outstanding as the song-and-dance duo Jimmy and Jimmy (usually played by two men). The joyous enthusiasm of their dance moves only seems to be heightened by their amazing precision. Their big number “The Grand Charleston” is one of the major highlights of the show.

One could say that with A Little Night Music (1973) and its sequence of waltz-time numbers, Stephen Sondheim had pretty much encapsulated the decadence of the 19th-century European aristocracy. One could also say that with Cabaret (1966), Kander and Ebb had given us a more vivd picture of Germany on the brink of disaster. Yet, there is a place for a musical like Grand Hotel that show us people, paralyzed both by their isolation and by social expectations, who don’t yet know that the world they live in is crumbling and who all want to know how best to live their lives. The wonderful irony of the show is that the person with the keenest knowledge of how to live is the one with the keenest knowledge that he will die.

Judging from the whoops that punctuated the show after the biggest songs and dance numbers and the wildly enthusiastic reception the audience gave the mid-season performance I saw, Grand Hotel draws an audience into the travails of each of its characters and tells a complex story through music and dance that few musicals seem to do nowadays. Kudos to the Shaw Festival for giving it such an impressive revival.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Matt Nethersole as Jimmy, James Daly as the Baron and Michael Therriault as Kringelein on the bar with the ensemble; Deborah Hay as Elizaveta; Vanessa Sears as Flaemmchen with ensemble; Kiera Sangster and Matt Nethersole as the two Jimmys. ©2018 David Cooper.

For tickets, visit www.shawfest.com.

2018-08-06

Grand Hotel