Reviews 2018

✭✭✩✩✩

created by Joan Littlewood, the Theatre Workshop & Charles Chilton, directed by Peter Hinton

Shaw Festival, Royal George Theatre, Niagara-on-the-Lake

August 12-October 13, 2018

Joan Littlewood: “Shut up. I want to look at the film”

Peter Hinton’s adaptation of the anti-war musical Oh What a Lovely War is conflicted both in conception and execution. The 1963 work was created by Joan Littlewood and the Theatre Workshop as a blistering indictment of the senselessness of war using World War I as its example. The Shaw Festival has mounted Oh What a Lovely War as one of three plays this year commemorating the end of the World War I, and Hinton has engaged historians to add material to the work pertinent to the Canadian role in the war. The problem Hinton faces is the contradictory task of simultaneously honouring the Canadian contribution to the war while satirizing the war itself.

If you wish to know what the original production of Oh What a Lovely War was like you need merely to read the programme note by former National Post critic Robert Cushman, who saw it. Act 1 of the original focussed on music hall songs of the period that encouraged patriotism and urged men to enlist. Act 2 focussed on the soldiers themselves and the horrors they endured as their commanders coldly calculated thousands of their lives away as part of their war strategy. The first act was to draw people into the show. The second was to hit them with the reality of what happened.

In his Director’s Note, Hinton says he is using Littlewood’s play as his “blueprint” but, in fact, he blurs Littlewood’s distinction between the two acts to such an extent that at the end of Act 1, it feels very much as if the show is over even though the action has only reached 1914. Under Hinton, Act 2 repeats the structure of Act 1 so thoroughly with sequences of scenes of battle, songs and numbers of killed totted up that far from inducing outrage the show only induces tedium.

The point of Littlewood’s Pierrot costumes was to ensure that we see actors playing clowns playing soldiers. By limiting the Pierrot costume to one actor only, Hinton eliminates one of Littlewood’s key distancing effects along with the notion that all those involved in the war were clowns in every sense of the word. We should see the incomprehensible drill sergeant (Jeff Irving) as a clown as well as the poor dupes he chews out. We should see the general Sir Douglas Haig (also Jeff Irving) as a clown as he idiotically sends more and more young men to purposeless deaths. Hinton wants to avoid this notion of the participants as clowns since it counteracts one of his central approaches to the play as announced in his added prologue.

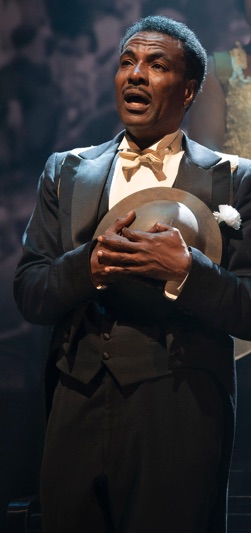

Hinton’s prologue has two functions. First, it tells the origin of the show. He introduces the character of Littlewood herself (Jenny L. Wright) who hears Charles Chiltern’s musical history of World War I on the radio and finds it far too sentimental. She wants to create a play that cuts through any nostalgia for a war that brought about over 10 million deaths. Second, a Master of Ceremonies (Allan Louis) along with the rest of the cast tells us that the Royal George Theatre was one of the three theatres in Niagara-on-the-Lake where troops waiting to be shipped overseas would be entertained. What he claims is that what we will see is the kind of music hall show that soldiers 100 years ago would have seen. The two functions of the prologue already introduce Hinton’s contradictory approach to the play. Following Littlewood, he wants to satirize the propaganda behind World War I and hence behind war in general. But, by adding the Canadian content, he adds material that Canadians wish to honour and commemorate. How do you celebrate Canadian efforts and losses in a war if you also emphasize that the war was utterly pointless and a waste of human life?

Hinton does include almost all of the music hall numbers in the original and many of the skits. The most important of these is the one that explains how the war started with arguments between personifications of Britain (Marla McLean), France (Kristi Frank), Germany (James Daly) and Russia (Jeff Irving). Unfortunately, Hinton has the four shout their lines so rapidly that the gist of what the disputes the four may have is completely lost. When Hinton stages the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand and his wife the Duchess of Hohenberg, we have no more idea why that should spark the onset of war than we did before the four-nations skit.

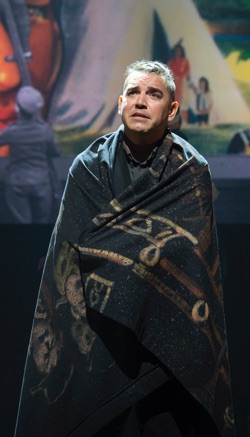

Hinton also shows that First Nations men were also initially refused. Yet, as the casualty rates rose, the government relaxed its restrictions and in 1915 actively encouraged First Nations people to enlist. The sting, as we learn in Act 2, is that First Nations veterans were not given the pensions or benefits of their White compatriots. These are important facts about the war that Canadians should know, but they do not fit into either of the categories of musical hall or of satire.

Hinton’s physical production suffers from the same contradiction in purpose as does his adaptation of the text. The upper half of the back wall of the playing area is taken up with a huge screen for projections. Littlewood used a screen above the playing area to project the statistics of lives lost compared to the paltry amount of land gained.

Hinton, however, projects old newsreels and archival photos. The problem is that the moving pictures being brighter than the playing area below with the figures larger and moving more swiftly automatically draws our eye towards the screen and away from the actors on stage. Only when the projection is a still photograph can we concentrate on the actors below. Yet, even when Hinton uses stills, he will have projection designer Howard J. Davis iris in and out of them or pan across them lending them movement when there should be none.

This does a great disservice to the actors in two ways. First, the projections are a complete distraction and undermine the actors’ efforts to capture our attention. Hinton even has his Joan Littlewood character say to the actors, “Shut up. I want to look at the film”. Second, we naturally will grant the documentary evidence of the film and photographs higher regard as historical testimony than we will the would-be satirical shenanigans of actors in a play. Attempts to satirize the war and its participants are completely overwhelmed by images of the real devastation that the war caused. In the end, one would much rather have seen a specially made documentary film about Canadians in World War I than this unsuccessful hybrid of play and film. Or, since Gerry Raffles has clearly done so much research to Canadianize Littlewood’s play, one wonders whether the effort would have been better spent in creating a new Canadian documentary play about the war.

In editing the play to include Canadian content, Hinton has sometimes removed the context of some of Littlewood scenes. Thus the lengthy ballroom sequence in Act 2 where the dancers gossip about who is rising or falling in estimation as commander makes absolutely no sense since we don’t know any of the people being discussed except, perhaps, Lord Kitchener. Yet, Hinton does come through with one beautifully staged scene. This is of the famed Christmas truce of 1914 when German and British troops sang each other Christmas carols and went into the no man’s land between the trenches to meet each other and exchange gifts. This, more than any other scene in the show demonstrates that the war was the product of the ambition and greed of government leaders, not of the common people themselves who had no grievances against each other. This scene which concludes Act 1 is so powerful that you really feel the show has nothing more to say about the war. And, indeed, as Hinton has framed it, it doesn’t. Only if you want to hear more of the fine singing of the ten-member cast is there any reason to return.

If the Shaw Festival were still to adhere to its original mandate, it would find that there are myriads of playwrights, poets and other writers who wrote between 1914 to 1918. Performance their works would provide us with insight into what people of the period were thinking. An evening of poetry and music from the young men whose lives were cut short in the war would be enough to honour them and highlight war’s evil.

It is perverse, to say the least, to try to force a British play satirizing British nationalism and imperialism into a simultaneous commentary on Canadian contributions to the war when Canadian nationalism is still a phrase with no meaning. This is especially true for World War I, which historians agree was the first time that Canadians across the country first thought of themselves as Canadians rather than members of a province or territory.

Despite the best efforts of its able cast, Hinton’s Oh What a Lovely War disappoints both as a version of Littlewood’s play and as a documentary of Canada’s involvement in the war. To commemorate the Great War, the Shaw offers GBS’s O’Flaherty V.C., the only play this season written during the war about the war, and, bizarrely, Shakespeare’s Henry V, which has been relocated to World War I. Surely, the Festival which once had such a long history rediscovering lost gems of the theatre, could have investigated the period of the Great War and done better.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Marla McLean (Briatin), Kristi Frank (France), Allan Louis (MC) and James Daly (Germany); Allan Louis as an African-Canadian; Ryan Cunningham as a First Nations Canadian; Marla McLean, Kristi Frank, Allan Louis and Kiera Sangster (on piano), James Daly, David Ball and Jenny L. Wright (on ground). ©2018 David Cooper.

For tickets, visit www.shawfest.com.

2018-08-07

Oh What a Lovely War