Elsewhere

✭✭✭✭✩

by Christopher Marlowe, directed by James Wallace

The Dolphin’s Back, The Rose Playhouse, London

March 11-29 & October 7-26, 2014

Duke of Guise: “Religion: O Diabole....

To think a word of such a simple sound,

Of so great matter should be made the ground”

I was lucky to participate in an historical occasion in British theatre. Christopher Marlowe’s play The Massacre at Paris (1593) received the first professional production of its extant text in over 400 years. Not only that, but the play was revived in the place, the recently discovered remains of the Rose Theatre, where it was first performed. The Massacre at Paris is usually considered the least of Marlowe’s seven plays primarily because no text overseen by the author exists. All we have is a memorial reconstruction – that is a text compiled by the actors who played in it. (This is the same situation as with the last two acts of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.) As a result only 1147 lines of dialogue remain – half the length of the average Elizabethan play.

What is so wonderful about The Dolphin’s Back production is that all of the aspects of the play that others have thought of as disadvantages, Wallace and his company have seen as advantages. The action comprises 22 scenes in only 90 minutes. They gives the play the breathless pace of a modern film. Except for two key soliloquies by the central villain, the Duke of Guise, the remembered dialogue is sharp and to the point. With 18 onstage slayings, the action has perhaps the highest body count of any Elizabethan or Jacobean play. In an earlier age this might have seemed unnecessarily gruesome, but after movies by Sam Peckinpah and Quentin Tarantino, this ultraviolent action not only seems up to date but appropriate for his historical subject matter – the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572 in which the Duke of Guise and his Catholic League gave Catholics free license to murder any Protestants they encountered. About 3000 were killed in Paris and more than twice that number in the rest of the country.

The Duke of Guise follows in Marlowe’s project of portraying men who seek power beyond the the bounds of religion. More than Tamburlaine and Islam, Barabas and Judaism or Dr. Faustus and Protestantism, the Duke of Guise explicitly uses virulent Catholicism as a way to gain earthly power. In his most extended speech, we see his similarity to Marlowe’s other overreachers:

That like I best that flyes beyond my reach.

Set me to scale the high Peramides,

And thereon set the Diadem of Fraunce,

Ile either rend it with my nayles to naught,

Or mount the top with my aspiring winges,

Although my downfall be the deepest hell.

What is different is the Guise’s plan to foment hatred to Protestants to his advantage:

For this, from Spaine the stately Catholic

Sends Indian golde to coyne me French ecues:

For this have I a largesse from the Pope,

A pension and a dispensation too:

And by that priviledge to worke upon,

My policye hath framde religion.

Religion: O Diabole.

Fye, I am ashamde, how ever that I seeme,

To think a word of such a simple sound,

Of so great matter should be made the ground.

The gentle King whose pleasure uncontrolde,

Weakneth his body, and will waste his Realme,

If I repaire not what he ruinates.

In general, The Massacre at Paris comes off like Shakespeare’s First Tetralogy, exchanging Yorkists and Lancastrians with Catholics and Protestants, edited down to only 90 minutes by a playwright like Edward Bond with a taste for cruelty and succinct dialogue. The trigger of the massacre is the marriage of the Protestant Henry of Navarre (Lachlan McCall) to the Catholic Margaret of Valois (Beth Park), opposed by Margaret’s mother Catherine de’ Medici (Kristin Milward). Soon enough after the marriage, the groom’s Protestant mother Joan III (Frances Marshall) and the Lord High Admiral of France, leader of the Huguenots (Richard Koslowsky) are dead. The Catholic Charles IX (John Sandeman) takes the throne, but he is seen as too soft on Protestants and Catherine de’ Medici, his own mother, plots his demise so that her younger, more malleable son Henry (James Askill) can become King of France. Yet, even he who becomes Henry III and whom Marlowe portrays as gay and surrounded by “minions”, develops a mind of his own. When the Guise has Henry’s chief minion Mugeroun (Jamie Sheasby) murdered, the Guise’s fortunes change and the man he sought to control now controls him.

The 12x20-foot performance space at the Rose Theatre consists of the wooden observation platform constructed to view the excavations of the archeological site underneath a modern highrise. Red rope lighting can be turned on to show the outlines of the theatre in the dark and the lighting is also embedded in the platform to show where the platform extended over one corner of the buried theatre wall. The seating for an audience of about 70 is in the form of a shallow C facing into the gloom over the theatre remains. There is no heat, but blankets are provided upon request.

Director James Wallace stages the play in modern dress with a minimum of furniture. He made imaginative use of the site – sometimes illuminating the red rope lights in the platform to delimit the Guise’s infernal domain, one time turning on the red lights on the full extent of the site when the Guise looks out to see the Seine run red with the blood of the massacred Protestants. At one point Wallace has a row of Huguenots killed execution style at the far end of the Rose Theatre outline, thus recalling many other genocidal mass executions since.

Wallace’s most brilliant idea is in his use of confetti. White confetti in 1 1/2-inch squares showers down upon the doomed couple of Navarre and Margaret. After that Wallace uses red confetti of the same size to represent blood that sprays copiously from every slash of sword or stab of dagger. The violence, as in Peckinpah or Tarantino, is both horrifying yet beautifully choreographed. As would not be possible with a liquid, the wooden stage is covered in more and more red with every murder so that we have a physical sign of the accumulation of deaths. Wallace even makes grimly comic use of confetti as liquid when the Guise urinates yellow confetti on the corpse of a slain foe or when he pours an ink pot of black confetti over his wife he views as forever stained.

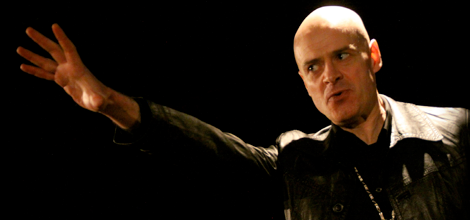

John Gregor is absolutely chilling as the Guise. He is not a victim of conscience like Shakespeare’s Macbeth or even an appreciator of irony like Richard III. As Marlowe writes him and Gregor plays him he is supremely cold and calculating, using reason to further his own goals whatever the cost in human lives. The rich calm voice Gregor uses contrasts with the horrific deeds he incites or describes.

His female counterpart is Kristin Milward as Catherine de’ Medici. Even as she wishes her progeny well, poison seems to drip from her honeyed words. Only at the Guise’s death can she release the perverse love for him that she had kept hidden. James Askill portrays Henry III as an adult who has remained a willful child. The Guise and Catherine assume that his weakness means he can be easily controlled, but they come to learn that childishness doesn’t understand duty of loyalty and is subject to tantrums. Lachlan McCall plays the sole voice of reason in the play, Henry of Navarre, who stolidly upholds the Protestant side. Marlowe’s audience would know, however, the historical irony that upon succeeding Henry III to the throne in 1589, Henry renounced Protestantism and became a Catholic.

All of the 13-member cast play multiple roles, but outside of the four above, the others play three or more roles. Beth Park captures the innocence of the young Margaret, who goes to her wedding rather as a lamb to slaughter. Frances Marshall has her finest moment as the Guise’s wife, caught in the act of writing to a lover. She plays wonderfully the vain attempts to hide the sense of panic and doom that come over her when the Guise catches her out. John Sandeman impresses as the good Charles XI, a man too good to last long in a world made vicious by the Guise and his mother. Jamie Sheasby stands out as Henry III’s chief minion, Mugeroun, a man rather like Gaveston in Marlowe’s Edward II, who is as ambitious for power as those around him, even willing to conduct an affair with the Guise’s wife.

A frequent trope in Renaissance poetry is the image of the world as a slaughterhouse. In The Massacre at Paris, Marlowe embodies that image on stage in an even more frightful way than Shakespeare does in Titus Andronicus or Julius Caesar. The title comes to have a double meaning since the St. Bartholomew Day’s Massacre takes up only the first half of the play. The second half is a massacre of a different sort where political intrigue leads one character after another to die in a spray of red confetti. The Dolphin’s Back has does a great service in proving how effective Massacre is on stage and how its uncompromisingly bleak view of humanity so well suits the present age.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) John Gregor as the Duke of Guise; James Askill as the future Henry III killing a Protestant; Beth Park Pleshé, Richard Koslowsky as Epernoun, Lachlan McCall as Navarre, John Sandeman (on floor) as Charles XI and Kristin Milward as Catherine de’ Medici. ©2014 Robert Piwko.

For tickets, visit www.rosetheatre.org.uk.

2014-03-31

London, GBR: The Massacre at Paris