Elsewhere

✭✭✩✩✩

by Heinrich von Kleist, directed by Michael Thalheimer

Schauspiel Frankfurt, Schauspielhaus, Frankfurt am Main

November 4, 2016-April 2, 2017

“Prinz Friedrich Falls a Victim to Regietheater”

People lucky enough to have seen Talk Is Free Theatre’s production of The Prince of Homburg in Barrie in 2015 should feel glad if that was their introduction to Heinrich von Kleist great play. Director James Kudelka, his creative team and his cast made a point of telling the story as clearly as possible while bringing out Kleist’s preoccupation with the interaction of appearance and reality.

The gratefulness to Talk Is Free Theatre was constantly in my mind as I sat through a production of the same play in the original German at Schauspiel Frankfurt under the totally misguided direction of Michael Thalheimer. Thalheimer may be a famous, award-winning director in Europe, but his production of Kleist’s play is an example of Regietheater at its worst.

Ontario audiences had an example of Thalheimer’s work when the Stratford Festival presented his 2001 production of Lessing’s Emilia Galotti in 2008. In that production of one of the classics of German drama, Thalheimer correlated the speed with which actors spoke their lines with their characters moral turpitude. Thus, the “bad” people spoke the most quickly and the “good” people the most slowly. While this provided a showcase for the the vocal acrobatics of the actors playing “bad” characters, the concept had nothing to say about the play and made the moral questions it raises simplistic.

The same is true with Thalheimer’s approach to Prinz Friedrich von Homburg. He deconstructs a classic play and in reconstructing it loses all the complexity inherent in the original. Making classic plays seem new may be a good thing. Making them mean less is not.

In the play Prince Friedrich has disobeyed his commander’s direct order in leading his troops at the Battle of Fehrbellin in 1675 against the Swedes but has won the battle, He is thus simultaneously a hero and a traitor. The punishment for the latter is death and the Elector of Brandenburg must decide whether to show grace or make an example of the Prince to show that law takes precedence over individual caprice.

When we first meet Prince Friedrich he is sleepwalking and the theme of what is real and what is imagined runs throughout the play. Thalheimer, however, has decided that the entire play is Friedrich’s dream. Friedrich remains in his nightshirt throughout the entire action. Making the whole play a dream, however, simply gives Thalheimer licence to do whatever he wants to with the text. Thus rather than beginning with members of the court speaking as they observe Friedrich, Thalheimer has Friedrich begin by repeating the word “Sieg!” (“Victory!”) so many times you wonder when Kleist’s dialogue will ever begin. (Friedrich never utters the word “Sieg” in the first act of the original.)

After this introduction Kleist’s dialogue finally begins but Thalheimer stages it so that all the characters are facing the audience and speaking their words into the auditorium. But since this is a dream there is no need for the staging to be realistic. These character are all placed at the very front of Olaf Altman’s set. We initially assume that, for reasons unknown, Thalheimer plans to use only this narrow portion of the stage until later when two semicircular doors behind the actors slide open to reveal a vast circular space behind them. Among the large number of Thalheimer’s perverse ideas is to leave this huge space almost entirely unused throughout the play. Except for once when the actors appear at the very back of the circular area and move forward, Thalheimer continues to place them in the narrow strip in front of the space. Is this avoidance of the most spacious area of the stage supposed to hold some meaning?

When Friedrich is arrested for treason and put in prison, Thalheimer has Friedrich taken to the centre of the circular space with suspension devices clearly attached to him. Bert Wrede’s already overloud music reaches a deafening climax and the circle suddenly drops out from under Friedrich who is left suspended in mid-air. This is a fantastic coup de théâtre depicting physically how Friedrich is literally left in suspense as to his fate and emphasizing the existential aspect of the play of how man should act when confronted with the void the surrounds him. The problem, however, is that Thalheimer leaves Friedrich visibly suspended like that for two acts of the play so that the surprise of the theatrical effect quickly wears off and becomes tedious.

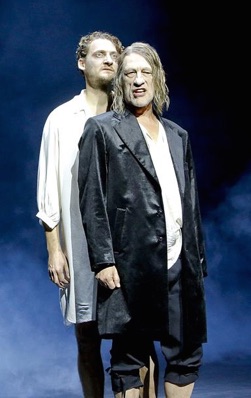

Despite the bizarre way that Thalheimer has directed the actors to deliver their speeches, it is still possible to see that the company is outstanding. As Prince Friedrich, Felix Rech maintains an extraordinary intensity throughout the uninterrupted hour and 45 minutes of the play beginning with his increasingly wild chant of “Sieg!” and escalating to his imprisonment in mid-air, first struggling against it and finally accepting it as his fate.

Yohanna Schwertfeger as his beloved Natalie is impressively fierce in her encounter with the Elector when she pleads for Friedrich’s life. Corinna Kirchhoff as the Electress brings a welcome note of common sense and human feeling to contrast with the otherwise extreme emotions of the other characters.

Even if this is supposed to be Friedrich’s dream, this makes no sense. The Elector is a man whom Friedrich respects and when the Elector pronounces his sentence, Friedrich obeys. Balkhausen costumes the Electress as a respectable aristocrat, so why has Thalheimer had her make the Elector into the mangiest character on stage? Wolfgang Michael lives up to his appearance by playing the Elector as if he were an inebriated Richard III. As with Thalheimer’s direction of Emilia Galotti, here again this highly acclaimed director can’t seem to help simplistically pigeonholing characters as “good” or “bad”.

Kleist’s original play ends with a replay of the first scene except that Friedrich is blindfolded rather than asleep and is presented again with the laurel crown intertwined with Natalie’s golden necklace. Friedrich assumes he is going to be executed only to find he is rewarded with both the crown of victory and Natalie’s hand in marriage. Thalheimer obviously doesn’t like this ending and so provides his own. There is no blindfold, no crown and no necklace. Natalie, fearing that Friedrich will be executed, exclaims, “O Erde, nimm in deinen Schoß mich auf! / Wozu das Licht der Sonne länger schaun?” (“O Earth, take me up into your lap / Why should I any longer see the sunlight?’). Thalheimer, deliberately misinterpreting the exclamation, then has Natalie kill herself by slitting her throat with a razor. Thalheimer’s gross breach against Kleist’s ending drew gasps from the audience and muttering until the play’s conclusion.

Natalie’s mode of uncalled-for suicide is all the more ridiculous since she still speaks the remaining lines she has. But, then, since this is all a dream, Thalheimer thinks he can do whatever he wants. Rather than the laurel crown scene, Thalheimer has the assembled cast repeat Friedrich’s chant of “Sieg!” until a sudden blackout. Thalheimer’s narrow view of the action is thus that the Elector pardons Friedrich only because he is a great fighter and will be needed in Brandenburg’s next battle. Any notion that the Elector is forcing Friedrich to undergo a test of his moral character is completely lost. And, of course, making the entire action into a dream means all the interplay between dream and reality in Kleist is lost since it is all forced onto the side of dream.

It is sad to see a great play abused in such a way. A great director should expand the meaning of a play not narrow it. And to waste the talents of such a capable cast for the sake of such a perverse concept is reprehensible. Yet, the website for Schauspiel Frankfurt refers to Michael Thalheimer as a regular fixture under the artistic directorship of Oliver Reese. On future theatre visits to Frankfurt, Thalheimer is a fixture I shall avoid.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Felix Rech as Prinz Friedrich and Stefan Konarske as Graf Hohenzollern; Yohanna Schwertfeger as Natalie, Corinna Kirchhoff as the Kurfürstin and Felix Rech as Prinz Friedrich; Felix Rech as Prinz Friedrich and Wolfgang Michael as the Kurfürst von Brandenburg. ©2016 Birgit Hupfeld.

For tickets, visit www.schauspielfrankfurt.de.

2016-12-09

Frankfurt, GER: Prinz Friedrich von Homburg