Elsewhere

✭✭✭✭✩

by Pablo Sorozábal, directed by José Carlos Plaza

Teatro de la Zarzuela, Madrid, ESP

February 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 17 & 19, 2016

“The Long-Delayed Premiere of Spanish Masterpiece”

Madrid’s Teatro de Zarzuela finally did justice to Juan José, the long-neglected work by Pablo Sorozábal (1897-1988). Zarzuela is Spain’s version of operetta, but it has a longer tradition than English, French or Viennese varieties since it stretches back into the 17th century. Sorozábal is considered the last of the romantic zarzuela composers and Juan José is his final work. He wrote the piece in 1968, but this is the first time it has ever received a fully staged production. The reasons why the work was never staged during General Franco’s regime that lasted until 1975 are fairly obvious. It criticizes both capitalism and the class system for the inescapable poverty of so many Spanish citizens, not in the light manner we might associate with operetta, but with the uncompromising force we would more associate with fully fledged opera.

Sorozábal based his opera on the play of the same name by Joaquín Dicenta (1862-1917), which became the second-most performed play in the Spanish repertory between its premiere in 1895 and 1939. Because of its strong social criticism a tradition developed of its being performed on May 1. Sorozábal subtitled Juan José a “drama lírico popular”, but explained that by “popular” he did not mean folkloric but proletarian. It is set in the slums of Madrid and, unlike Puccini’s La Bohème, deliberately does not romanticize the life of the people who live there.

The story concerns Juan José, a construction worker and the son of a prostitute who left him to beg throughout his childhood. He used to be a drunken and violent man until he met Rosa, whom he defended when she was being accosted by several men. Since then, the two have been living together and he has totally reformed his life because until meeting her he had never experienced love.

The problem is that Juan’s foreman, the wealthy Paco, is also interested in Rosa and would like her to be his mistress. To this end he pays the procuress Isidra to turn Rosa against Juan and to have her agree at least to meet Paco. When Juan comes across Paco flirting with Rosa in a bar, Juan physically attacks him and warns Paco never to come near her. But this altercation has serious consequences. Paco fires Juan from his job and Juan finds that no one will hire him. Rosa, who had already lost her job before the fight, now lives in abject poverty with Juan and they get by only by selling their few possessions.

This bleak narrative shows that a single man standing up to those in power has no effect. They can take away his employment and ruin his life. The implication, of course, is that what society needs is a general uprising of the disenfranchised against the powerful for there to be any progress in bettering the lives of the poor. It’s not surprising that a production of the work was cancelled in 1968 and again in 1979. Juan José was not performed until 2009 and then only in concert.

Although Sorozábal is known as a zarzuela composer, Juan José is much more like a modern opera. The only spoken passage is when a convict reads out a letter that the illiterate Juan José receives in prison. Unlike the more familiar zarzuelas, the music is seldom based on dance rhythms. It is very much in the mould of Puccini but stripped of its lushness, the brass in particular contributing to the feeling of harshness. Sorozábal uses the unusual technique of having characters begin a melodic aria but then cutting it off after the first stanza. Sorozábal seems to be showing that he could write a Spanish opera like La Bohème if he chose to, but that the real world of poverty that his opera depicts doesn’t allow expressions of sentimentality to survive for long.

Despite this, he does provide each of the principals with at least one long scena, gratefully written to display their vocal prowess. The most surprising of these is the long, showpiece Sorozábal writes for Paco. Despite being the villain of the piece, Paco has the most gorgeous aria, orchestrated unlike that of all the other characters in the style of Richard Strauss with reminiscences of the silver rose theme. No doubt, this is to make Paco stand out from the others because he has the allure of wealth. Full-voiced tenor Antonio Gandía sings it beautifully.

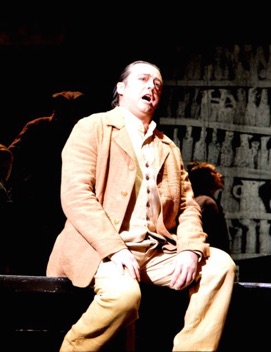

Rosa’s biggest aria concerns her longing for a better life and is written in a more straightforward Puccinian mode. Carmen Solís uses her rich, expressive soprano with great effect. Sorozábal gives Juan José two long arias, each in a less identifiable modern style likely to make him appear the man of the present. Ángel Ódena has a strong, dark-hued baritone and is an excellent actor. His characterization of Juan José not just in these arias but through the entire work is a devastating portrait of desperation.

In fact, the entire production demonstrated that one does not hear lesser voices when one attends the Teatro de la Zarzuela. All the voices were as strong if not stronger than those at the Teatro Real. Among the fine contributions are Silvia Vázquez as Toñuela, Milagros Martín as Isidra, Rubén Amoretti as Andrés and Ivo Stanchev as the imprisoned criminal Cano.

The only concept that director José Carlos Plaza forced on the piece was to create a non-naturalistic background for the action. Paco Leal’s set designs included three-dimensional pieces mixed with two-dimensional sketches of objects. Each scene featured rubbish piled in a corner as if to underline how the lower class is regarded. Plaza also had choreographer Denise Perdikidis move the dancers, who filled out the stage as tavern-goers of prisoners, in the stylized manner one sees in German expressionist films. While this worked well enough in the prison scene it didn’t feel very organic in the more naturalistic tavern scenes. The one time it worked best was in a fine scene in the tavern when the crowd upstage reacts to the guitar-playing and singing offstage then freezes. In this case, the stylization kept the focus on Ángel Ódena as Juan José singing of his love for Rosa.

Miguel Ángel Gómez Martínez conducted the Orquesta de la Comunidad de Madrid with passion and vigour although the auditorium of the Teatro de la Zarzuela is not as resonant as one might wish. Sorozábal makes use of Leitmotivs, such as an upwardly spiralling phrase cut short that seems linked to the theme of thwarted hope. Only through a second viewing could a person understand better how Sorozábal uses these motifs and to what effect.

Sorozábal’s Juan José is a like a de-sentimentalized La Bohème or a more tuneful and more politically focussed Wozzeck. Now that it has finally had its first full production, one hopes it will remain in the repertory of the Teatro de la Zarzuela, even though it would be at home in any opera house willing to present an unjustly neglected 20th-century Spanish work. The Teatro de la Zarzuela is home to a form of music theatre specific to Spain and the countries it influenced. Opera-loving visitors to Madrid should make a point of experiencing this form which, as Juan José demonstrates, is willing to take on much more complex social topics than is usually the case for what we think of as operetta. Appreciating zarzuela is made even easier since the company projects surtitles in both Spanish and English. There is no excuse then not to attend and to wonder why zarzuela has not spread beyond the bounds of the Spanish-speaking world.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Ángel Ódena as Juan José and Carmen Solís as Rosa; Antonio Gandía as Paco; Ivo Stanchev as Cano and Ángel Ódena. ©2016 Fernando Marcos.

For tickets, visit http://teatrodelazarzuela.mcu.es.

2016-02-22

Madrid, ESP: Juan José