Reviews 2000

✭✭✭✩✩

by Éric-Emmanuel Schmitt, translated by Roeg Sutherland, directed by Anthony Page

Mirvish Productions, Royal Alexandra Theatre, Toronto

February 17-April 1, 2000

“An Enigma in More Ways Than One”

We in Toronto should be grateful to the Mirvishes for having programmed two recent plays from France in their 1999-2000 season, namely the delicious comedy “Art” (1994) by Yasmina Reza and “Variations énigmatiques” (1996) by the increasingly popular Éric-Emmanuel Schmitt. While we have become used to seeing the latest work by English, Irish and American playwrights, it seems we very seldom see contemporary plays from outside North American and the English-speaking world. Let us hope these two plays may the beginning of a more international diet for theatre-goers as was the case in the 1960’s and 1970’s.

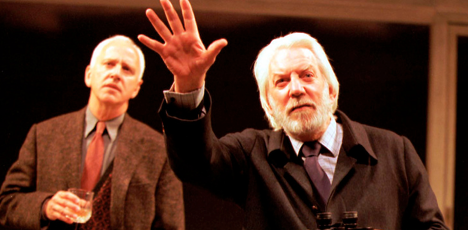

The production of “Enigma Variations” comes to the Royal Alex from the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles primarily as a star vehicle for veteran Canadian actor, Donald Sutherland, and marks his return to the stage after an absence of 20 years. The production is rather a family affair as it is produced by Francine Racette, Sutherland's wife, who first drew his attention to the play, and is translated by by his son, Roeg. Sutherland plays a Nobel prize-winning author, Abel Znorko, who has just published his latest novel to great acclaim. It is in the form of an exchange of letters between a character also named Abel Znorko and a woman named Eve and is dedicated to someone known only as “H.M.” Znorko, who for 15 years has been living as a recluse on a private island in the far north of Norway, has allowed a journalist, played by John Rubinstein, the rare chance to interview him. The journalist, however, has come to exact from Znorko an admission that not only are “Eve and “H.M.” the same person but that he knows who “H.M.” is. Further, he claims the novel is not a work of fiction at all but the actual correspondence between the two.

The play moves forward very much as an old-fashioned mystery, though with a certain malicious humour, as deliberately withheld information gradually comes to the fore culminating in a series of surprising revelations. While the structure may be conventional, the intent, given Schmitt's training as a philosopher, seems to be to demonstrate the thesis that all knowledge is mediated, or on a personal level, that one person can never truly know another person, even one he has loved. The “H.M” known to the journalist is so completely different from the “H.M.” known to the novelist that it is difficult to believe the two are the same person. Thus, as in the play “Art”, characters are shown to see in another person only what they wish to see and never the person as he or she really is.

The thesis of the play, however, is undermined by the contrivances of the mystery-play structure. By comparison, “Art” is by far the more elegant and satisfying treatment of the same theme. “Art” begins as what seems an insubstantial comedy that becomes increasingly more profound as the playwright allows one implication after another to grow from the interaction of the characters. “Enigma Variations” announces its claim to profundity fairly early on with much talk of “the existential loneliness of the self”. As the Royal Alex programme states, Schmitt’s plot has “more twists, turns and surprises than an Agatha Christie thriller. This is only too true. Christie’s plots, though entertaining, are often far too contrived to be plausible. One of the later “twists” in “Enigma Variations” is so unlikely that became too difficult willingly to suspend my disbelief. This "twist" is where the play has been heading all along, but one ruefully comes to see that the thesis, not the characters, has been driving the action.

Up until this later plot twist, “Enigma Variations” had been an entertaining if not especially gripping evening. Ming Cho Lee’s handsome set, Robert Wierzel’s subtle lighting and Jon Gottlieb’s highly effective soundscape combine to create a sense of a lonely house in landscape both bleak and beautiful. Both actors give very fine performances. Schmitt's Abel Znorko is a very meaty role for Sutherland, far more substantial that the kinds of parts he’s been playing in films lately, requiring the sustained development of his character from the haughty, disagreeable misanthrope we first meet to the docile, shattered man near the end of the play. Sutherland was in full command and one could only regret that his absence from the stage has lasted so long.

Unlike the usual two-character, star-vehicle, the role of the journalist Erik Larsen did not devolve into that of an aide mémoire for the star. Rather, John Rubenstein skillfully moved his character from beleaguered politeness at the start to anger and rising confidence until his character takes on a moral authority at the end of the play. While the Anthony Page’s direction was clear and detailed to a degree, I found, given the amount of information each characters is withholding at the start, that the actors should have been encouraged to suggest more fully that there is a subtext to what they are saying. This would help increase the tension in the first part of the play and motivate Larsen's return to a man who offers him nothing but insults. Then some, though not all, the withheld information, when revealed, would strike us less as bolts from the blue.

Fans of Sutherland need not hesitate. It’s a pleasure to see him on stage and it is an all-too-rare event. He received a standing ovation at the end of the performance and has done so every night. (He also received applause and bravos just for turning around when the play started!) Fans of mysteries à la Christie also need not hesitate. Anyone, however, who is looking for a recent French play that does not unravel the more one thinks about it will have to hope that “Art” returns to town.

©Christopher Hoile

Photo: John Rubenstein and Donald Sutherland. ©2000 Geraint Lewis.

2000-03-14

Enigma Variations