Reviews 2008

✭✭✭✩✩

by J.B. Priestley, directed by Jim Mezon

Shaw Festival, Festival Theatre, Niagara-on-the-Lake

May 21-November 2, 2008

"A Mystery Inside an Enigma"

“An Inspector Calls” (1945), the best-known play by J. B. Priestley (1894-1984), is currently receiving its second production at the Shaw Festival. Directed by Jim Mezon, stepping in for an ailing Neil Munro, the acting is absolutely first-rate and the story is gripping. Peter Hartwell gives the show a concept production that many will find perplexing since it ultimately makes little sense of the action. Luckily, it is not so intrusive that it distracts from the performances that key to making this unusual play work.

The Shaw Festival last presented the play in 1989 in a conventional production at the Royal George Theatre. The story is simple enough on the surface. The wealthy Birling family are celebrating the engagement of their daughter Sheila to Gerald Croft, the scion of another wealthy family. In the midst of their celebrations the mysterious Inspector Goole appears with plans to question each member of the family in relation to the suicide of a young woman known to them under different names. It soon transpires that each of the Birlings and Gerald Croft has been involved with the young woman in some way that could be seen as contributing to her suicide. But what precisely are they guilty of?

The action is set in a single drawing room and stage time equals real time. Priestley, however, uses the familiar structure of the drawing-room mystery for political and metaphysical purposes. The classism and sexism the Birlings represent has likely led to innumerable lives of destitution. As a play from 1945 set in 1912, it gives the audience an ironic perspective on the Birlings’ attitudes and on some of the predictions they make, such as idea that Germany will never go to war. The play’s surprise ending (which I will not reveal) calls into question when and even if the events we have witnessed have actually taken place. The play’s reputation rose in 1992 when director Stephen Daldry presented the play at the National Theatre in fantastic surrealist production designed by Ian MacNeil which went on to run in various theatres in the West End for almost ten years. Since then it has been impossible for major theatres to return to simpler method of presenting the play.

In Daldry’s production the residence of the Birling family was depicted as a large doll-house-like Edwardian mansion perched on a stalk bursting through a desolate landscape like some kind of bizarre desert bloom. Off in the distance were other such structures suggesting that Birlings were not alone in their views. Meanwhile, people in 1940s dress occasionally strolled past these structures and their Edwardian-clad inhabitants. One can note reminiscences of Daldry’s production in Hartwell’s design. The Birlings’ drawing room is strangely located in what seems to be the top of a gloomy tower accessible only by elevator, thus also portraying their separation from the world below. Inspector Goole is clad in 1940s garb not the Edwardian dress of the Birlings. But there are some new features. Whenever the dead girl is mentioned, a shadow flits past the frosted windows that encircle the top of the tower. Rusting chains overhang the Birlings' dining table and move when the elevator in is use, implying that the Birings exclusion from the world below has also enslaved them.

Hartwell has placed the dining room and drawing room on a kind of peninsula extending from the upstage circular row of doorways. Once Inspector Goole enters this peninsula slowly begins to glide back and forth with its hinge just in front of the central elevator door in imitation, one presumes of the pendulum of a clock. Meanwhile, the lighted clock visible above the elevator door, its hands permanently at six-thirty also begins to revolve. It is known that Priestley was fascinated with J.W. Dunne’s theory of time that viewed past, present and future as occurring simultaneously not sequentially. Since the play’s ending questions whether what we have seen has actually happened, it would seem more logical to do just the opposite of what Mezon does, that is to show the conventional Birlings immersed in conventional time that suddenly comes to a halt when Inspector Goole enters. As it is, the only advantage of the present design is that it allows us changing views of the onstage furniture.

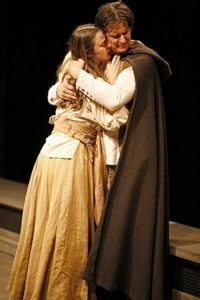

The cast is uniformly excellent. As Inspector Goole, Benedict Campbell is a calm insistent presence who does exactly what Priestley say he does--to draw the characters out through a subtle range of questions until they betray their most deeply held secrets. Peter Hutt as the Birling paterfamilias Arthur, is the only actor given to overemphatic delivery that betrays underlying weakness rather than strength in confronting Goole. Graeme Somerville is excellent as the seemingly faultless Gerald Croft, whose façade of propriety is easily shattered. Andrew Bunker, who has frequently shown his gifts as a comic actor now has the chance to show he is equally impressive in the wholly serious role of the tortured Eric Birling. Not merely his heavy drinking but his posture and uncontrolled speech suggest that Eric is wrestling with a troubled conscious even before Goole arrives. Mary Haney plays Sybil Birling, the mother of the family as grande dame and the most supercilious of the bunch, so much so we wonder whether Goole will ever manage to make her see a single fault in herself. In contrast, Moya O’Connell as the daughter Sheila is very sympathetic and the first to see what Goole is after. She sees that the secrets involving the dead women are merely a symptom of the life of lies the Birlings live and that Gerald Croft unquestioningly accepts.

The atmosphere of moral and supernatural mystery is enhanced by Paul Sportelli unnervingly moody music and by Kevin Lamotte’s lighting that suggests that interpersonal sparks flying inside the Birlings’ towering household are reflected in a thunderstorm outside. Stephen Daldry’s great re-imagining of the play is going o be hard to surpass for some time, but the acting of the Shaw company is in no way inferior to that famous production. In fact, some of Daldry’s staging attracted attention away from the text, especially at the very start of the play, which never happens here. If you are in the mood for a mystery that moves from a whodunnit to a “who-didn’t-do-it?” to a “what-really-happened?” then head straight for “An Inspector Calls”, a play that will intrigue you in more ways than any ordinary mystery will.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photo: Benedict Campbell, Mary Haney, Andrew Bunker, Peter Hutt and Moya O’Connell. ©Emily Cooper.

2008-07-01

An Inspector Calls